Excerpt

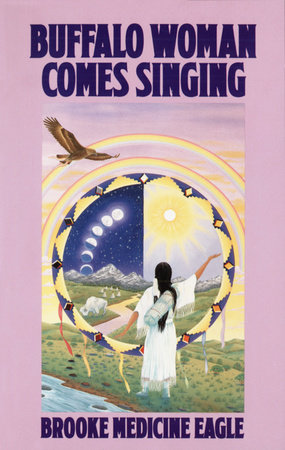

Buffalo Woman Comes Singing

INTRODUCTION

In our present time of ecological and social crisis, all of humanity is looking for new ways to move forward, ways that will solve current problems without creating new ones (as we have in the past with gasoline engines and other technological “advances”). One place it has been obvious to turn is the native peoples of our lands, whose ancient ways reveal a deep ecology that is at once both physical and spiritual, even though their practice is varied in the hundreds of tribes on this continent. These ancient teachings call us to turn primary attention to the Sacred Web of Life, of which we are a part and with which we are so obviously entangled.

This quality of attention—paying attention to the whole—is called among my people “holiness.” Holiness is never understood to be focusing attention on a white-bearded old man figure as God, or on any specific spiritual figure, but rather enlarging our awareness to consciously include and respectfully consider All That Is, All Our Relations—all beings, energies, and things in the larger Circle of Life.

This sacred focus on holiness as an integral part of everyday life is central to Native American teachings, and is of great value to us today. White Buffalo Calf Pipe Woman, the mystical woman who came long, long ago to bring the sacred pipe as a symbol and reminder of the holiness, stands today as a central figure in the spiritual way of the Lakota Sioux and many other native tribes. The symbolism of the two men in the story of White Buffalo Woman told in the Prologue, as well as her pipe and teachings, are clear metaphors about how we are to approach life on Mother Earth if we two-leggeds—we humans—are to make it through this next century and create a new way of being on Earth that will open us to our full human-ness.

Central to White Buffalo Woman’s message, and to all native spirituality, is also the understanding that the Great Spirit lives in all things, enlivens all forms, and gives energy to all things in all realms of creation—including Earthly life. Several things follow from this understanding:

‣ We, and all things in the web of life, are related. We are not only children of our Mother Earth, but also of our Father, the Great Spirit. And thus we are all each other’s brothers and sisters.

‣ Primary to our beingness, and to our relationships in the larger hoop, is the feminine energy of nurturing and renewing—of ourselves, each other, and all those peoples in our Sacred Circle of Life, especially the children.

‣ Each of us has Spirit within us to develop and bring forward. Each thing and being contains Spirit’s living flame—consciousness and aliveness—and thus has the right to be respected and honored for its unique power and gift.

‣ Through each of us Spirit can speak, and thus guide us and our people.

‣ Each of us is a small, yet significant part of the wholeness and at the same time contains the wholeness. As in a hologram, where each piece contains the whole picture yet the picture becomes clearer as more and more pieces are joined together, so our harmony, unity, and cooperation with All Our Relations are necessary for the full picture of life to be revealed. It is only through this harmony that we will be able to move forward.

‣ Our participation with the Great Creator in the continuing unfoldment of life is essential. Thus, renewal dances, such as the Corn Dance among the Pueblo peoples of the Southwest, and the Sun Dance among the Plains peoples; the harvest dances and honoring dances of other peoples in the Circle of Life, such as animal dances; plus all the other ceremonies honoring the cycles of the seasons and of life, are both our duty and our joy. These rituals focus participants toward the unfolding unity that can create life anew.

Interestingly enough, the various native tribes or groups practiced these principles within their own group and with Mother Nature, yet they seldom extended this practice to other groups or tribes. A unified dance of all people, a rainbow dance of creation, did not occur to them. This is why the sacred dream of the Lakota visionary, Black Elk, was so important. When he was only nine years old, in the late 1800s, he had a vision of all races and colors dancing together to renew the Tree of Life. (This story is told in Black Elk Speaks by John Neihardt.) He was so uncomfortable with what had been revealed to him that he did not even speak of it until later in his life when urged to do so by an elder. Yet Black Elk’s vision of a universal, global dance of creation and celebration that will be required in order for life to continue is absolutely vital to us all in this present day. In fact, we must not only renew the dances of creation, we must also extend them to include All Our Relations. This is the task before us, and it cannot be completed “until we all join in a joyful dance of life.

In our process of transforming and healing ourselves and the world in the present, it seems important that we understand something of our place in North American history. We need to know where we are and who we are being called to be, whether or not we are Native American. Let us first look at one of the structures used by many early native peoples as they attempted to create a peaceful and harmonious life.

From the earliest times, our native people have had councils—often comprised of all males or all females—each holding a powerful focus of energy for the people. In many tribes, the men had an impressive war council—but they also had a peace council as well. During the latter years of the fighting between Indians and whites in the late 1800s, the finest of our Native prophets began to receive information from Spirit. They were told that their people must make peace and eventually come into spiritual unity with the oppressors, in order for anyone—most especially their own children of coming generations—to have a good life, and for the Tree of Life to blossom again for all.

At that time, the war councils and warrior societies, which were devoted to conflict and did not serve the people, essentially became obsolete. Our world was changing rapidly. The intention of Peace was set within the deep spirit of the Americas, and yet our struggle since then has been to make it real in our daily lives. The great prophets from time immemorial spoke to our people of returning to the oneness—the brother/sisterhood that was modeled on this continent at the time of the great Sun centers in the South, when the Dawn Star walked among the people (see chapter 7). But for the most part, our Native people, as well as those from across the waters, engaged in divisiveness, warring, and separation, and in conflict over territory. Thus Indian and white alike were joined in a karmic endeavor to complete the warring and return finally to oneness and peace.

To give an example, in his classic work, The Cheyennes, E. Adamson Hoebel speaks about the Cheyenne tribal council of peace chiefs. He explains:

The keystone of the Cheyenne social structure is the tribal council of forty-four peace chiefs. War may be a major concern of the Cheyennes, and defense against the hostile Crow and Pawnee a major problem of survival, yet clearly the Cheyennes sense that a more fundamental problem is the danger of disintegration through internal dissension and aggressive impulses of Cheyenne against Cheyenne. Hence, the supreme authority of the tribe lies not in the hands of the aggressive war leaders but in the control of the even-tempered peace chiefs, all proven warriors.

Yet this peace council of male elders eventually failed to control the Bow Society, the warriors who wanted to go to war indiscriminately, without consulting their spiritual sources or the council of elders. In the subsequent fighting with other Indian tribes, a third of all the warriors and most of the chiefs on both sides were killed. The Sacred Bundle of Arrows—the central sacred object of the tribe, representing masculine, procreative power—was lost to the Cheyennes. Other serious physical and spiritual calamities befell them as well, all of which clearly pointed out the danger of indiscriminate warring, when what actually should have been happening was the making of peace and the nurturing of the people. Because of all this, the male Cheyenne peace council eventually lost its power and function.

The message here is the primacy that the pursuit of peace and holiness must have in the minds, hearts, and actions of the people. In days of old, this concern extended only to those within the tribe. Now we have matured into a new time of understanding: we realize that peace and harmony must be generated not only within the entire family of two-leggeds but within the full Circle of Life as well.