Excerpt

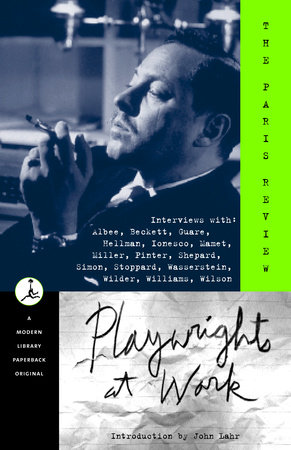

Playwrights at Work

INTRODUCTIONby John Lahr

We need stories; but, as the twenty-first century begins, most of the stories we're told on television and in film are corporate creations, calculated to pick the pockets of the public. The theater's charm and its power is that it is the last bastion of the individual voice, where the secrets of the psyche and the sins of the society can be explored in community with others. "I regard the theater as the greatest of all art forms, the most immediate way in which a human being can share with another the sense of what it is to be a human being," Thornton Wilder tells

The Paris Review in this volume. He goes on: "This supremacy of the theater derives from the fact that it is always 'now' on the stage." Ours is an age of perpetual distraction, a virtual reality which Wilder didn't live to see; "the now" is what a large part of the video-addicted public will pay anything to avoid. Entertainment has become atomized, inevitably, the cross-fertilization that is implied in the word

civilization (whose root is the Latin for

city) has been eroded by the new technology. The public has become habituated to its solitude; it has also grown increasingly uncomfortable in large groups. The onslaught of technological escape, which tickles the society to death, has weakened the appetite for active play. When all is provided, nothing need be sought. In the republic the result is a palpable psychic mutation--a passive, credulous, restless mass at once overexcited and underinformed. At its best, theater is an antidote to the whiff of barbarity in the millennial air. "My feeling is that people in a group, en masse, watching something, react differently, and perhaps more profoundly, than they do when they're alone in their living rooms," Arthur Miller says here. In the dark, facing the stage, surrounded by others, the paying customer can let himself go; he is emboldened. The theatrical encounter allows a member of the public to think against received opinions. He can submerge himself in the extraordinary, admit his darkest, most infantile wishes, feel the pulse of the contemporary, hear the sludge of street talk turned into poetry. This enterprise can be joyous and dangerous; when the theater's game is good and tense, it is both. "We live in

what is, but we find a thousand ways not to face it," Thornton Wilder says. "Great theater strengthens our faculty to face it." The playwright has to call the story out of himself; the audience has to call the energy out of the actors. This responsibility has its excitements and its disappointments. Whether you talk, eat, make out, or leave a film, the performances remain the same; the movie happens without a public. The play needs an audience. So the paying customer enters the theater on his mettle; he has a certain unstated but real emotional responsibility to the group. He has to rouse himself from his inveterate entropy and to be alert. "The theater made everybody in the audience behave better, as if they were all in on the same secret," John Guare says in these

Paris Review interviews, recalling the empowering magic of his childhood theatergoing. "I found it amazing that what was up on that stage could make these people who didn't know each other laugh, respond, gasp in exactly the same way at the same time."

A playwright is an altogether different literary species from a novelist, who marshals words merely onto the page. "What is so different about the stage is that you're just

there, stuck--there are your characters stuck on the stage, you've got to live with them and deal with them," Harold Pinter says. The novelist never sees the reader walk out of his book. He is not writing in space and time; he doesn't have to coax a character he's created to speak the words as written. Consequently, a playwright is a raffish hybrid, a kind of cross between a recluse, a roughneck, and a con man. He lives both in his head and in the world. To ensure the life of his work, he has to be both a charmer and a killer. "You must keep people happy backstage because that affects what's onstage," John Guare says, describing what he privately refers to as "Diva Watch." "During a run, the playwright feels like the mayor of a small town filled with noble creatures who have to get out there and make it brand-new every night. When a production works, it's unlike any other joy in the world."

And when it falls, no failure is so public, so humiliating, and so instant. "Mr. William Randolph Hearst caused a little excitement by getting up in the middle of the first act and leaving with his party of ten," Lillian Hellman says, recalling the floperoo

Days to Come. "I vomited in the back aisle. I did. I had to go home and change my clothes. I was drunk." The playwright learns quickly to develop a thick carcass, or at least to fake one. To succeed, the play has to surmount all sorts of obstacles--hurdles of money, casting, directing, rewriting--before it reaches the public. Because of this ferocious struggle, playwrights are a nervy, bumptious, competitive, often outrageous lot. As the reader will discover in these pages, they are also good, high-spirited company. For instance, speaking of

The Sisters Rosensweig and aspects of herself in one of her characters, Wendy Wasserstein includes "the ability to get involved with a bisexual." She adds: "Hey--when's the mixer!" Eugene Ionesco describes the first night of

The Bald Soprano, when members from the dadaist College de 'Pataphysique, to which he was a satrap, turned up at his opening wearing its highest decoration,

La Gidouille, "which was a large turd to be pinned on your lapel.... The audience was shocked at the sight of so many big turds, and thought they were members of a secret cult." Sam Shepard recalls his contentious, alcoholic father going to see one of his plays for the first time, a New Mexico production of

Buried Child, which was loosely based on the father's family. "In the second act he stood up and started to carry on with the actors, and then yelled, 'What a bunch of shit this is!'" Shepard explains. "The ushers tried to throw him out. He resisted, and in the end they allowed him to stay because he was the father of the playwright."

In a sense playwrights are masters of their own ceremonies--rituals whose style of provocation the public in time learns to follow and to enjoy. In

The Bald Soprano and

The Lesson Ionesco mounted a theatrical attack on bourgeois assumptions about psychology and language. "We achieved it above all by the dislocation of language," he tells

The Paris Review. "Beckett destroys by language with silence. I do it with too much language, with characters talking at random, and by inventing words." The sense of unlearning---of making new paths in the public imagination--is part of theater's job description. "To have a play draw you in with humor and then make you crazy and send you out mixed up!" John Guare says, speaking of playwrights who influenced his ambition for mischief "When I got to Feydeau, to Strindberg, Pinter, Joe Orton, and the 'dis-ease' they created, I was home." It is Samuel Beckett who has taken theater to the outer limits of uncertainty--a revelation which occurred when Beckett returned to Dublin after World War II and found his mother almost unrecognizable from Parkinson's disease. In Lawrence Sheinberg's account of his meetings with Beckett, the playwright describes his intellectual volte-face. "The whole attempt at knowledge, it seemed to me, had come to nothing," Beckett tells him. "It was all haywire. What I had to do was investigate not-knowing, not-perceiving, the whole world of incompleteness."

Although the playwrights assembled here talk about the physical circumstances of playwriting, about the history of their plays and their influences, about their lives, none of them can quite answer the question every interviewer wants to know: how does the play happen? There is no truthful way to answer such a question. "A play just seems to materialize; like an apparition it gets clearer and clearer and clearer," Tennessee Williams says. About his masterpiece

A Streetcar Named Desire, he continues: "I simply had the vision of a woman in her late youth. She was sitting in a chair all alone by a window with the moonlight streaming in on her desolate face, and she'd been stood up by the man she planned to marry." A play is a piece of happy synchronicity where the writer's ideas, his collaborators, and his luck cohere into a narrative which is a kind of gossamer mystery. "Good plays are a mystery," Neil Simon says here. "You don't know what it is that the playwright did right." He adds: "If the miracle happens, you come out at the very place you

wanted to."

A play is for every playwright a journey into the unknown, a trip for which each has his own idiosyncratic method and mission. For instance, Tennessee Williams, who spent eight hours a day for thirty years at his craft, says he writes plays as a kind of "

emotional autobiography" in which his characters are correlatives who chronicle the shifting spiritual battle in his own very divided nature. Harold Pinter, by contrast, works entirely out of his unconscious. "I don't know what kind of characters my plays will have until they ... well, until they

are. Until they indicate to me what they are." He adds: "I don't conceptualize in any way. Once I've got the clues I follow them--that's my job, really, to follow the clues." Many of the writers here bear witness to being taken over by the voices and almost channeling the voices who inhabit them. "There were so many voices that I didn't know where to start," Sam Shepard says, of beginning to write his off-off-Broadway plays. "It was splendid, really; I felt kind of like a weird stenographer." Even for a Broadway playwright like Neil Simon, the experience is the same. "I've

always felt like a middleman, like the typist," he says. And Eugene Ionesco, true to his surrealist first principles, dictates his plays to his secretary. "I let characters and symbols emerge from me, as if I were dreaming," he tells

The Paris Review. "I always use what remains of my dreams of the night before. Dreams are reality at its most profound, and what you invent is truth because invention, by its nature, can't be a lie." He adds: "Writers who try to prove something are unattractive to me, because there is nothing to prove and everything to imagine. So I let words and images emerge from within."

Playwrights always work against time. Their plays give shape to the moment; in turn, the moment defines them. The sense of the clock ticking is part of the unstated poignancy of both their art and their lives. Tennessee Williams, for instance, builds the sense of time's passing and the waning of creative energy into his drama. "I don't ask for your pity, but just for your understand--not even that--no," Chance Wayne says in the last line of

Sweet Bird of Youth. "Just for your recognition of me in you, and the enemy, time, in us all." But whereas Williams's life and his art seem to flee from the prospect of an ending, Samuel Beckett's work embraces it. "It's a paradox, but with old age, the more the possibilities diminish, the better chance you have," Beckett says here. "With diminished concentration, loss of memory, obscured intelligence what you, for example, might call 'brain damage'--the more chance there is for saying something closest to what one really is." He adds: "How is it that a man who is completely blind, completely deaf, must see and hear? It's this impossible paradox which interests me. The unseeable, the unbearable, the inexpressible." All the playwrights included here, each in his or her own way, are trying to trap what is invisible to the community and to give it shape. "If anything new and exciting is going on today, it is the attempt to let Being into art," Beckett says. He adds: "Being is constantly putting form in danger." The different shapes of the plays mirror the different shapes of the souls whose Being speaks down to us uniquely on through the eras--a powerful, beautiful, necessary spiritual connection with our moment and with our times gone by.