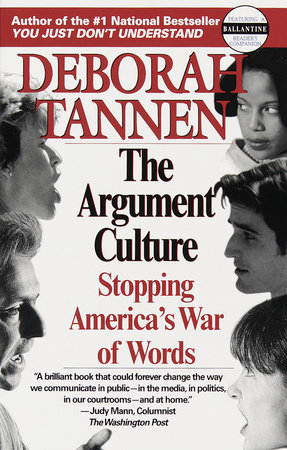

The Argument Culture

Stopping America's War of Words

Deborah Tannen

Ebook

October 24, 2012 | ISBN 9780307765536

AmazonApple BooksBarnes & NobleBooks A MillionGoogle Play StoreKobo

Paperback

February 9, 1999 | ISBN 9780345407511

AmazonBarnes & NobleBooks A MillionBookshop.orgHudson BooksellersPowell'sTargetWalmart

About the Book

In her number one bestseller, You Just Don't Understand, Deborah Tannen showed why talking to someone of the other sex can be like talking to someone from another world. Her bestseller Talking from 9 to 5 did for workplace communication what You Just Don't Understand did for personal relationships. Now Tannen is back with another groundbreaking book, this time widening her lens to examine the way we communicate in public--in the media, in politics, in our courtrooms and classrooms--once again letting us see in a new way forces that have been powerfully shaping our lives.

The Argument Culture is about a pervasive warlike atmosphere that makes us approach anything we need to accomplish as a fight between two opposing sides. The argument culture urges us to regard the world--and the people in it--in an adversarial frame of mind. It rests on the assumption that opposition is the best way to get anything done: The best way to explore an idea is to set up a debate; the best way to cover the news is to find spokespeople who express the most extreme, polarized views and present them as "both sides"; the best way to settle disputes is litigation that pits one party against the other; the best way to begin an essay is to oppose someone; and the best way to show you're really thinking is to criticize and attack.

Sometimes these approaches work well, but often they create more problems than they solve. Our public encounters have become more and more like having an argument with a spouse: You're not trying to understand what the other person is saying; you're just trying to win the argument. But just as spouses have to learn ways of settling differences without inflicting real damage on each other, so we, as a society, have to find constructive and creative ways of resolving disputes and differences. Public discussions require making an argument for a point of view, not having an argument--as in having a fight.

The war on drugs, the war on cancer, the battle of the sexes, politicians' turf battles--in the argument culture, war metaphors pervade our talk and shape our thinking. Tannen shows how deeply entrenched this cultural tendency is, the forms it takes, and how it affects us every day--sometimes in useful ways, but often causing, rather than avoiding, damage. In the argument culture, the quality of information we receive is compromised, and our spirits are corroded by living in an atmosphere of unrelenting contention.

Tannen explores the roots of the argument culture, the role played by gender, and how other cultures suggest alternative ways to negotiate disagreement and mediate conflicts--and make things better, in public and in private, wherever people are trying to resolve differences and get things done. The Argument Culture is a remarkable book that will change forever the way you perceive the world. You will listen to our public voices in a whole new way.

The Argument Culture is about a pervasive warlike atmosphere that makes us approach anything we need to accomplish as a fight between two opposing sides. The argument culture urges us to regard the world--and the people in it--in an adversarial frame of mind. It rests on the assumption that opposition is the best way to get anything done: The best way to explore an idea is to set up a debate; the best way to cover the news is to find spokespeople who express the most extreme, polarized views and present them as "both sides"; the best way to settle disputes is litigation that pits one party against the other; the best way to begin an essay is to oppose someone; and the best way to show you're really thinking is to criticize and attack.

Sometimes these approaches work well, but often they create more problems than they solve. Our public encounters have become more and more like having an argument with a spouse: You're not trying to understand what the other person is saying; you're just trying to win the argument. But just as spouses have to learn ways of settling differences without inflicting real damage on each other, so we, as a society, have to find constructive and creative ways of resolving disputes and differences. Public discussions require making an argument for a point of view, not having an argument--as in having a fight.

The war on drugs, the war on cancer, the battle of the sexes, politicians' turf battles--in the argument culture, war metaphors pervade our talk and shape our thinking. Tannen shows how deeply entrenched this cultural tendency is, the forms it takes, and how it affects us every day--sometimes in useful ways, but often causing, rather than avoiding, damage. In the argument culture, the quality of information we receive is compromised, and our spirits are corroded by living in an atmosphere of unrelenting contention.

Tannen explores the roots of the argument culture, the role played by gender, and how other cultures suggest alternative ways to negotiate disagreement and mediate conflicts--and make things better, in public and in private, wherever people are trying to resolve differences and get things done. The Argument Culture is a remarkable book that will change forever the way you perceive the world. You will listen to our public voices in a whole new way.

Read more

Close