Excerpt

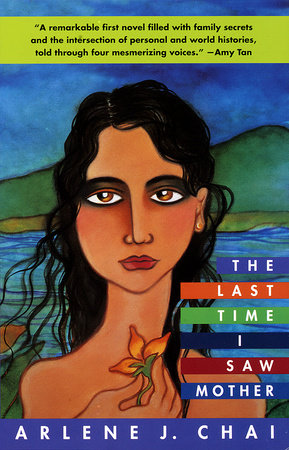

The Last Time I Saw Mother

CARIDAD

“I have been summoned

by my mother.”

MY MOTHER NEVER WRITES. So when the mail arrived that day, I was not expecting to find a letter from her. There was no warning.

I had spent the morning running away from the lecture notes I had taken the night before at TAFE college. I was on my second term, doing a travel course which I hoped would get me back into the workforce.

By eleven I had run out of things to do. Outside, the Hills Hoist made squeaking sounds as it turned in the wind, like a giant weather vane stuck in a huge, flat, mossy roof. A gusty south wind blew and the clothes that hung from it flapped about madly, making snapping sounds. It wasn’t so long ago that I had hung them out, carefully slipping hangers into shirts, pegging legs of pants onto the line, so they dangled there as if belonging to a row of people doing headstands, only their torsos, arms and heads had been chopped off by some unseen hand. They were almost dry.

The pot plants that lined the deck had all been watered and fed. And the cobwebs that some industrious spider had intricately spun from one leaf to another like lace had been swept aside. Even the empty potato-chips packet that the fat kid next door had thrown over the fence had been picked up and deposited in the kitchen bin.

Three used cups stood in the kitchen sink and a small pool of coffee sat at the bottom of each. One last cup and I promised to settle down and study. My notes sat in a neat pile at the far end of the kitchen counter, looking at me reproachfully. I emptied the last few drops of milk from the carton. Not enough there. The liquid remained a dark brown. I took a sip. Then poured the rest down the sink.

TOURISM IN AUSTRALIA WAS written at the top of the first sheet in my neat handwriting. I looked at the page more closely, inspecting how I’d written out each letter. No open tails in my f’s, p’s and y’s. My b’s, l’s and t’s all had complete, closed loops.

“You’re introverted and secretive. You’re also the kind of person who finishes what she starts … that’s what these loops say,” so said an old college friend back home in Manila who dabbled in esoteric things like handwriting analysis. Now getting started had become a problem.

“Stop being so hard on yourself. What did you expect? A miracle? It takes some time to get used to studying again,” Marla told me just the other night when I came home feeling frustrated, announcing to her I was quitting.

These days, my eighteen-year-old daughter preaches patience to me. Some of her words sound like the ones I used with her when she would sit in front of the piano, getting impatient with fingers that refused to play a Czerny passage with the fluidity required.

“I hate Kuhlau and Bartok is boring!” she used to complain.

“Be patient and you’ll get it right,” I would tell her.

Now Marla plays mother to me. Just last night when I got home from TAFE, she opened the door, an apron around her waist, gave me a kiss, and said, “I made some spaghetti bolognaise. Why don’t you go take a shower and I’ll heat some up in the microwave for you.” I spent the rest of the evening sitting in the lounge room, hair still wet from the shower, a bowl of spaghetti on my lap, listening to her at the piano.

Marla is in her first year at the Conservatory of Music. I still find it hard seeing her in that classical institution. She is like a stranger in her new look: one morning she went to her hairdresser in Paddington and returned home with her beautiful long hair gone.

“Had it chopped off!” she announced as I stared at her razor-cut hair that barely made it to her ears. Soon after, the blues, reds, yellows and greens in her wardrobe made way for somber blacks.

“Black is dramatic,” she explained.

“That’s her growing up and making a statement,” Jaime, my husband, said, shrugging in resignation.

As she sits in front of the piano, the picture she makes is of a punk playing classical music. The image is made even more jarring by her Chinese-Filipino-Spanish face. Her catlike, Oriental eyes, high cheekbones, and olive complexion.

I read somewhere that we may change our path, choose our future. But our beginnings stay with us forever. I had Marla while Jaime and I still lived in the Philippines. She was eight before we brought her to live in Sydney. And like every migrant, her country of birth has left its mark on her.

“To confuse the issue,” she often says, “I’m not only Manila-born, convent-school-educated, speak English and Tagalog plus a bit of Chinese and curse fluently in Spanish, but now I reside in Australia as well.”

Crazy mixed-up kid.

TOURISM IN AUSTRALIA. I read the title for the hundredth time. It was then that I heard the clink of the mailbox. I did not see the mailman come. The brick wall that enclosed the front garden obscured my view of the street. But every week day between twelve and two, he always came. I got up, glad for an excuse to escape my notes. Saved by the mailman.

As I stepped out onto the driveway, three teenagers with spiky hair thundered down the footpath on their skateboards. I caught a glimpse of them through the gaps between the timber palings of the gate. Across the street, Tripod, the three-legged dog that lived in number thirty-six, peed against a post as Big Tom, his owner, waited patiently for him to finish.

The mailbox scorched my fingers as I reached in to pull out the envelopes and rolls of junk mail that seemed to find their way there every day. The top envelope had a little window. A bill. The second had a tiny, almost illegible, spidery scrawl. From Jessie, I could tell.

Jessie—she hated her name—was an old childhood friend from my Manila school days who now lived in Michigan. She was a practising neurologist, a far cry from the girl whose hem Sister Bernadette once ripped out because her skirt rode too many inches above her ankles, showing more flesh than the nun thought decent for a young girl in a convent school.

Jessie wrote often then as her clinic was going through another slow month. “It’s as if there’s a season for being sick and a season for being well. The latter is very bad for business.”

The last envelope had a Manila postmark but it was not from Mia. My cousin Mia did not write out her letters longhand. She worked off a keyboard. “I’ve become computer literate,” she said over the phone. “Have to keep up with the kids.” So I knew the angular handwriting, the long slanting letters that spelled out my name and address, did not belong to her.

Curious, I ripped the envelope open and pulled out a folded sheet of blue stationery paper like the ones my father used to write on when he was alive. Only now the signature at the bottom read “Mama.”

It was a strange sight that letter with the unfamiliar writing. Strange and funny for it occurred to me that if I were asked to put a face to those loops and dots, the way one puts a face to a name, I would not have been able to. After all the years of being her daughter, I had never seen my mother’s writing until that moment. If it was the only way I could claim her, identify her, she would have been lost to me.

Not that the letter was a letter at all. It was a short note giving voice to a command. I could almost hear her say the words. For they were so like her. Curt. Brief. To the point.

“Come home, Caridad. I need to speak to you,” was all it said. I have been summoned by my mother.

Was Mama sick? I rang Mia in Manila.

“No … no, nothing’s the matter.”

“So why does she want me to come?”

“She’s old, Caridad, you know how old people are. They need to be humoured … So just do as she asks, okay?”

“I don’t understand this …”

“You won’t, until you come home.”

Mia knew more but she wasn’t telling. That much I was sure of because we had known each other forever. I was three, she, five, when we found in each other a sense of companionship that would last through the years. One crazy afternoon when she had come over to my house to play, we sneaked into the bathroom and opened the medicine cabinet where my father kept his shaving things. We took one of his razor blades. Then, after a few minutes spent summoning up enough courage, we cut each other’s thumb and squeezed the cut to get the blood out before putting our thumbs together. With our blood finally flowing in each other’s veins, we swore to be best friends forever.

Mia was my first cousin, Tia Emma’s youngest daughter. Tia Emma was Mama’s youngest sister. Mia was the youngest of six children and had no place in the games and chatter of her older siblings, while I, being an only child, longed for a friend. We were inseparable as children and remained close through the years.

When Jaime, Marla and I left Manila, Mia and I stayed in touch, writing each other long letters, exchanging hundreds of photographs and talking on the phone for longer than we could afford. It is she who has patiently passed Mama’s messages on to me, for she has taken to calling on my mother to see how she goes. Not an easy task as Mama has always been difficult to deal with. So when Mia said, “Just do as she asks,” I booked my flight, knowing she believed it was important I make this trip home.

That night as I lay in bed, a thought entered my mind. If Mama was well, was I being called home for another reason? Has she heard? Did she know?