Excerpt

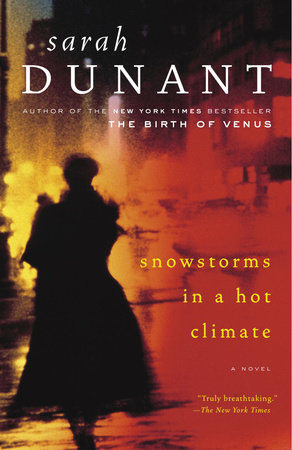

Snowstorms in a Hot Climate

One

London 1985

I was happy that day because I was leaving and I like departures. I understand why some people find them untidy, emotional affairs, but I have always had a hankering after them. That is one thing Elly and I have in common. I find airports the best places to leave from. Of course they have none of the romance of railway stations—no clinging good-byes framed in billowing steam, no last-minute touches through half-opened windows, no nineteenth-century echoes to gild the going. No, airports are altogether more anesthetized points of dispatch, conceived and constructed for efficiency, not grace. But then that is what gives them their power, what makes them so exhilarating. Because from the moment those automatic doors glide apart to welcome you inside, nothing, as far as I can see, need ever be the same again. However bad you are feeling, however caught in the quicksand of failed chances and repeating patterns, airports are the new horizon, the conveyor belt of travel, which in due course will disgorge you in some exotic location where you will be happy, fulfilled, or at the very least, different. Such were my fantasies in the departure lounge of Heathrow Airport on that last Thursday in July.

The preliminaries were over. I had arrived out of the heartland of the city alone, struggling with my own cases, anonymous. I had had my ticket torn, my baggage checked, and my name punched into the computer. I had taken the habitual last walk around the outer compound, bought a clutch of glossy magazines, and then, leaving my last handful of small change on the counter, I had sauntered through Immigration to the world beyond. In the flight departure lounge the BA 177 boarding light was already flashing, winking adventure. On the other side of the ocean Elly was waiting for me. The journey had begun.

Of course it is all fallacy, the romance just a creation of admen and soft-porn merchants. Travel changes nothing except the location. And whoever met anyone remotely interesting on a plane? There was an Egyptian woman I sat next to on a flight from Cairo to Paris once. She had silver hair and sleek features like Nefertiti. But she slept the whole way from takeoff to touchdown, and when she did finally open her magnificent almond eyes, it turned out she didn’t speak a word of English. And as for the myth of erotica in the water closet—well, whoever believed that story anyway?

Not me. And certainly not now. Herded in through the giant metal tube, I discovered this particular DC-10 filled with ordinary earthbound people. I ignored them all and barricaded myself into my window seat, content to keep my own company for the next seven hours.

Outside the aircraft the tarmac shimmered in the heat haze of the engines. I pushed my nose against the reinforced glass and thought of London. Six-ten p.m. Ten million people going home. The Northern Line at rush hour: just another carcass in the truck, the smells of sweat and cheap perfume amid flapping newsprint.

At Camden Town I stand at the top of the escalator and watch myself ride up toward me, face set, shutters drawn. A dissolve to the key in the lock, followed by the unholy silence of a house where everything is exactly as I left it. The plants, perhaps, have grown imperceptibly; the flowers have drooped a fraction. I pour myself a drink and sit waiting for the tension to subside. And I congratulate myself on another day beaten into submission. I consider the people I could call, except, of course, I know I never will. In the end I eat an apple, lie on the sofa, and read a book on Icelandic myths. And every day a thousand planes take off, heading in a thousand different directions. All it takes is the doing.

Back inside the bird I caught a glimpse of a man making his way down the aisle. Something to look at. Tall, slender body; a storm of fair hair and chiseled features; the kind of bone structure that turns women into willing wives and men into homosexuals. My eyes flickered and passed on. Such gourmet dishes are not for me. They are too rich, and I do not have the table manners. Anyway, on the evolutionary scale I have always found handsome princes too close to frogs for comfort. The fairy tale brought Elly to my mind; small, sparkling Elly, whose face had almost become a blur in my memory. And I wondered for the umpteenth time since her letter dropped onto my stairwell whether we would actually recognize each other over the airport barrier, or if somehow two years and transatlantic separation would have changed the contours of us both. Parrot fashion I recalled the words of her leaving: Elly curled in a wicker chair, frowning across at me on that day she bought her ticket for Mexico.

“I didn’t want to tell you until I had decided. You mustn’t be upset, all right? I’ll miss you, you know that, but I just have to get out for a while. Be a stranger, unconnected. It’s not permanent. Just a trip—a short walk in the Americas. Six months, a year at most, and I’ll be home . . .”

And then I remembered the shadows in her letter, the small cramped writing, as if someone had pushed her into a corner and was blocking her way to the door. And as the engines of the DC-10 roared skyward, I wondered about the time in between.

Once we were airborne, with London miniaturizing beneath us, smart stewardesses in multicolored aprons started loading up the drinks trolleys. Once they began their trundling passage forward there would be no escape till they had passed. On the aisle seat a corn-fed American in a checked jacket was already settled into a Mickey Spillane. He grunted as I squeezed past him. A man in tune with his fiction. There would be violence before I returned. In the loo I bolted myself in and, as the light snapped on, turned to face the mirror.

Maybe now is the time for you to see what I look like. I will use only solid, simple words. That way you won’t be seduced by novelistic adjectives. I am tall and have big bones. I was told by my grandmother that I am the proof of the peasant stock in the family. My great-grandfather, it appears, was a delicate, slender aristocrat who was called out to India to serve the French Raj in Pondicherry and went looking for a sturdy woman who would bear heat and children with equal equanimity. He came upon a country girl from Toulouse with rippling long fair hair and big muscles. She gave him eight children in quick succession and then died of smallpox. My grandmother has a lock of her hair in a casket she keeps by her bed. I am, it seems, her physical, if not her spiritual, heir. Except for one thing. She was beautiful and I am not. I am what I think is called “heavy featured.” My mouth is too large and my nose too prominent. My eyes are all right, but since they are the mirror to the soul, I have got into the habit of keeping them half closed. You can’t be too careful.

On my way back to my seat I passed Mr. Magnificence. He was sitting in the first row of Club Class, long legs encased in smart soft leather boots stretched out in front of him. I followed the feet upward. Expensive trousers, tailored shirt, and the shower of golden hair over the sculptured rock of his face. Why are people so attracted to beauty? There is no real reason why good-looking lovers should be any better in bed. Except perhaps that they get more practice. This particular specimen was clearly aware of his charisma. I disliked him instinctively. He was drinking a large Bloody Mary, playing carelessly with the cocktail stirrer in the glass, while flicking through a maga- zine on his lap. Next to him on an empty seat lay a book, cover upward. The Meeting at Telgte by Günter Grass. His taste surprised me.

Back with the plebeians, Mickey Spillane was making a play for real life. He had moved to the center block and was talking animatedly to the well-dressed woman sitting next to him. They both had drinks. He had already eaten his peanuts. I chased the moving trolley and came back with a plastic glass full of ice, and a hoard of three bottles of Scotch. The first taste of whiskey over ice was hot and cold at the same time. It brought back images of America: dimly lit bars with country and western on the jukebox and pool tables covered in green baize under low-slung lamps.

I took another sip and settled back into my seat. Outside there was a vast skyscape, pure blue over snow-white clouds. England had gone. I invited Queen Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, to look over my shoulder across the ocean of cloud. She was one of the lesser-known heroines of Anglo-Saxon England; I had written my thesis on her and occasionally still kept in touch, just to see how Anglo-Saxon intelligence might respond to twentieth-century wonders. At this altitude she would probably have expected to see God. I screwed up my eyes and fantasized a host of chubby cherubim, poking their heads out of the clouds. A landscape of divinity. Do people have revelations on aircraft? And has the rate increased since the booze became free? Aethelflaed, bored by the lack of marauding armies to conquer, faded back into history. I opened my second bottle and waited for a visitation.

Later, as the sky turned crimson, the button-bright hostess brought dinner. I pushed a few carrots around the plastic plate but left the dead chicken as votive offering to Thor, just in case of thunderbolts. On the stereo I plugged into Handel’s oratorio. Coffee came and went. I had a brandy and wondered if I was drunk enough to sleep. I closed my eyes, but Elly’s letter was burning a hole in the bottom of my bag. The compulsion to reread what I already knew by heart was overwhelming.

Not here, not rubbing spaces with so many other people. I clambered out of my seat, realizing as I stood up that the alcohol had, after all, had some effect. In the loo my face looked significantly more yellow under the strip lighting. It seemed too early in the trip to have contracted hepatitis. It must be the booze. I sat down on the toilet seat and, from the inner recesses of my bag, dug out the crumpled airmail envelope. Elly, in trouble.