Excerpt

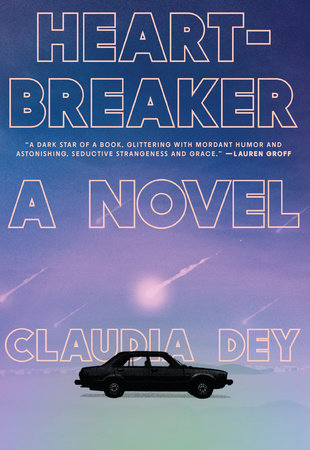

Heartbreaker

This is what I know: she left last night. My mother, Billie Jean Fontaine, stood in our front hallway with a stale cigarette in one hand and her truck keys in the other. The light in our hallway was broken or dying so it flickered above her head, throwing shadows across her face. I don’t know how long she was standing there watching me.

I was only feet away on the couch in my nightpants trying to arrange my body like the woman in that Whitesnake video. It was not going well. The television was on, and I had our telephone receiver pressed hard against my left ear. My ear had gone numb listening to Lana on the other end breathing heavily, which made me picture, unfairly, Lana’s dog, a dog, unlike our dog, of low intelligence. Together in silence, we watched Teen Psychic. The show was already at the love line, making it close to seven o’clock, and 1985, and late October. Teen Stewardess was on next, and for this, I felt deep excitement.

I had my outerwear smoothed flat on my lap. With a black permanent marker, I was filling in the cap letters I had written across the back. I would debut and copyright these later at the bonfire. Note there is no such thing as permanent. Especially in a marker you find in a snowdrift. I also found my camo outerwear in said snowdrift, the snowdrift that borders the north highway outside Neon Dean’s pink bungalow, which on Free Day can be a bonanza. A few other things to keep in mind at this moment: I had almost a hundred dollars in small denominations hidden inside the album covers in my bedroom, twelve jerry cans of gasoline stashed in the woods behind our house, hair to my tailbone I had recently tried to self-feather, and my mother had not come downstairs for two months.

“I am going into town.” My mother spoke this astonishing sentence not to me but to the cold air around me. She had not left our bungalow since the end of July, and it was now almost three months later. Winter had set in. Outside, the trees were skeletal, and the hunters were urinating on their hands to warm them. The men called this dicking the hands. I dicked my hands to turn my keys. Same. Dicked my hands right there on my front porch. Same. Had to dick my hands to cock my rifle. This was the kind of talk you might hear if you went into Drink-Mart for some homemade alcohol. There, under a half-busted chandelier, listening to Air Supply, the men of the territory gathered to clean their rifles with their wives’ old tan pantyhose while being stared at by a wall covered with the beautiful heads of our animals.

Air Supply. A band name none of us wanted to read into.

I joined my mother in the hallway. I had not seen her upright for weeks and now looked down at her scalp, the hair broken in places. Beauty, what is beauty? Beauty is cheap. Beauty is common. Beauty is luck. My father, The Heavy--known for many things but mostly his severe facial issues--loved to say when he first laid eyes on my mother, it was not like the stories you hear about beauty. A man struck down by a woman’s beauty. Taken by a woman’s beauty. No. Not at all. My father liked to say when he first laid eyes on my mother, he had never seen anyone quite so alive.

She was wearing her indoor tracksuit. It hung from her frame and was the color of dirty water. I knew not to touch her, and this was difficult, so I pushed my hands into the large pockets of my nightpants. I had done my bloodwork that morning and was still feeling a bit faint. Moving quickly from the couch to the doorway, I was seeing sparks, and the strobe-light effect of the dying bulb above us was not helping, so I tilted my head down slightly and leaned against the wall, looking but not feeling casual. Of late, I had become a fainter, and this was a most useful quality as it meant instant departure to a dark and neutral space. When my mother and I used to talk, we agreed that HELP was a flawless word. That even if you reordered the letters, people would still completely get your meaning. PHLE.

My mother wasn’t wearing her sport socks or her house sandals, the usual combination for a territory woman who finds herself indoors at home at night, which is always. Her feet were bare and marbled. Her toenails had yellowed, and her shins looked sharp and blue, as if they could slice through wood. In my bedroom, I liked to listen to hot men sing about hot women while studying the images of disease. We had very few books in the territory, but we did have one thick volume that contained nothing except pictures and descriptions of diseases. It didn’t even pretend to offer advice or remedies--just gory, vivid photos of people from the neck down with their various inflammations, and their identities protected. The book gave me solace, and some basic Latin.

Though she wasn’t moving, my mother appeared to be in a rush. She gripped the truck keys, making her knuckles white as chalk. I wanted to write birth across one set and death across the other. She studied my collarbone. You made this collarbone, I wanted to remind her, though I knew not to speak to her. She was in the middle of something and could not be interrupted. Or so she’d told me. In our last conversation. If you could call it a conversation.

I slid down to the floor and closed my eyes to steady myself. I knew my mother was still there because she had taken on a new smell. It was a mineral smell.

This past summer, shortly before she stopped leaving our bungalow, when she still went into town for Delivery Day and her shifts at the Banquet Hall, but it was clear something had come over her, I watched my father dig another man’s grave. Poor, dead Wishbone. The women of the territory had gone to pay their respects to Wishbone’s widow. Get her mind off it. Fashion her hair. Bleach her freezer. Put on the Rod Stewart. My mother had not. She stayed in her bed. She didn’t turn to face us when she asked my father and me to please leave her there. She wasn’t up for it. Wasn’t feeling herself. I had just turned fifteen and was finally at the age where I could go with my mother to these sorts of events. Instead, I ended up with the men at the graveyard. My father was incredible with a shovel, and the men had to tell him when to stop digging, he had gone down far enough, there was plenty of space for a casket. For ten caskets. Jesus, The Heavy, the men said to my father chest-deep in the grave, pulling the shovel from his hands. Take a load off, the men said. The high mound of fresh dirt beside us, and then under our boots as we made our way back to our truck, identically hunched and with our arms touching. My father and I sat in the front seat for a long time. I had been trying to tan my face though it was becoming clear I was allergic to the sun. So far, this is not the best day of my life, I wanted to say to The Heavy. What has come over her? I wanted to ask him. Do you even know?

All around us, the men in the graveyard wore mirrored sunglasses. Some were shirtless and looked barbecued in the July heat. They would alternate the positioning of their hands on their shovels so their musculature would be even. My father did none of these things. Sitting in the driver’s seat, he was an uneven man blinded by the sun. I looked through the front windshield to the sky, which was such a bright blue, I felt embarrassed by it. Strategies for happiness. My mother had said it was important to try to come up with these. I pictured a supply plane dropping nets filled with useless, shiny things like mesh bathing suits and white leather furniture. I wanted a headlamp that worked. I wanted a Camaro. I wanted a Le in front of my name. Pony Darlene Fontaine. Le Pony Darlene Fontaine. Le Pony. That’s what everyone will have to call me from this day forward, I said to no one.

Eventually, my father turned the key in the ignition, and Van Halen came on. It was the tape with the angel on it who even as a baby you could tell would be a future convict. I loved that tape. It was all my mother had been listening to for months. I would watch her in our unfinished driveway, staring into the middle distance in her winter coat while the truck shook with the music.

My father wrenched the tape from the player. He threw it into our backseat. I don’t even know, his face seemed to say, I don’t even know. I made a visor out of my hand and put it above his eyes. He drove home like it was an emergency.

This was the smell my mother was giving off now in our front hallway--an unfinished space, an open body cavity, an open grave. Our dog came bounding down the stairs and wound herself between my mother’s legs. I worried the force of her would knock my mother down. I watched my mother’s heart lift the threadbare fabric of her tracksuit. I searched for the Latin translation of cancer of the dreams. I pulled myself to standing. Our dog sat at my mother’s exposed feet, taking my place. Our dog had perfect posture. She did not want your companionship. She wanted your throat and your hot parts. She loved only my mother. She was too old to be alive. All around us, the men and women of the territory chased after and screamed for their dogs. Our dog had never run away. Our dog had never barked. Not once.

My mother went for our front door. She had to kick things out of the way to get to it, agitation like a shock. There was a blue tarp in our living room, hanging behind our television set, where Teen Stewardess had just begun, and through it I could see my father’s shape. LHEP. A high whine. He was sawing through lumber. He would have his hearing protection and snowmobile goggles on. He was adding a room to our bungalow that would be a room just for my mother. Where nothing would be asked of her. Where she could return to her thinking, to what she called her native thinking.

My mother pulled the front door open with her sure grip, her athlete’s grip, and the northwest wind came hurtling in at us. It was a wind that could carry tires and shatter glass. You had to walk with your back into the northwest wind. There was a partial moon, and you could see the snow was blowing sideways. Our dog paced at my mother’s feet, lush and frantic. It had been months since she had truly felt the weather. She had braids all through her coat. My mother, looking ahead and then back, her mouth moving slowly, but sounding like herself for a moment, said with tenderness, “I had forgotten all about you.” I told myself she was speaking to me. At last, she was speaking to me.

My mother came to this place as a stranger. Now I feared she was retracing her steps out. Returning to a world she had refused to describe to me. Billie Jean Fontaine. Billie Jean. Was that even my mother’s real name?

We live on a large tract of land called the territory. When the Leader and his followers first laid claim to it some fifty years ago, they called it Upper Big Territory. Now, it’s just the territory. The descriptors were redundant. Aerial view: two thousand square miles of forest. Population: 391. We started as a single busload searching for the end of the world. Now, look at us.

We didn’t spread out.

The north highway cuts a straight line through town, and this is where you will find most of our local businesses. The residential streets branch off from the north highway in a grid. They are not named. In the territory, we go by bungalow number. Lana’s is 2. Neon Dean’s is 17. Ours is 88. Guess how many bungalows are in the territory? Exactly. One of my favorite jokes is to pretend I’m lost. I will be riding my ten-speed in my mother’s powder-blue workdress, her purse strapped across my body and her ATV helmet on, and I’ll see someone at the edge of their property, and I’ll flag them down and say, Yeah, so, hey, there I was on the north highway, made a couple of turns, and now I am just all spun around. Just totally lost. Cannot seem to find my way back home.

Bungalow after bungalow, built all at once when the territory began. Small cement porches. Snowmobiles and swing sets in the yards, and the girls with show hair long like their mothers’, long like their dogs’, and the men and boys shaved to near bald. Let me give you the lay of the land. The men love to start a lecture this way. Our dogs are white here, and there are no leashes. It is acceptable to make a leash-like mechanism for your children, but not for your dog. Your dog is an animal and to forget her nature is to forget your own. If you would like to see a dog on a leash, turn on your television. We will barbecue under a tarpaulin for our dogs in the dead of winter, but we will not give them names. You. Come. Here. Get. Names are for our people not our dogs. If you would like to see a dog with a name, watch Lassie. It’s on at four. Duct tape in medicine cabinets. Radios with batteries carried from room to room. Always the sound of a truck in the distance. Knowing the trucks by sound. Who is approaching. Who is not going home. Deadbolts on garage doors. A bear on your property after the thaw. Motion-detector light. Gunshot. Beards a sign of mental damage. Gunshot. Tanning beds in our sunken dens, and many of our people the shade of anger. Smelling like coconut oil in line at Value Smoke and Grocer. None of the men going by their birth names. Wishbone, Sexeteria, Hot Dollar, Fur Thumb, Visible Thinker, Traps. The Heavy. Let me give you the lay of the land: men, women, children, loaded rifles. Hearts stop. Dogs, trucks, winter, fucking. Hearts break.