Excerpt

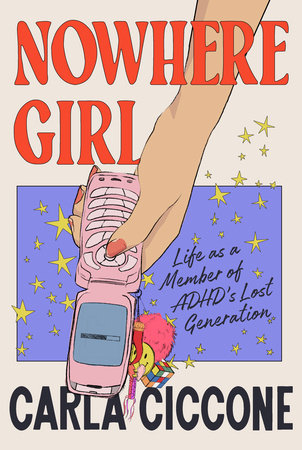

Nowhere Girl

IntroductionIn My Head

The way I spoke to myself in early motherhood was diabolical, but I’d been perfecting the art of motivational meanness for decades. It helped me get shit done, and it hid the war within me under a veneer of togetherness that I constantly fought to maintain.

Keep smiling, I said as we walked by the nurse’s station. A nurse asked how I was feeling. “Great!” I said.

You stupid liar. Round and round I went, pushing my beautiful newborn through the cesarean recovery wing in her plastic hospital bassinet. I ignored the piercing pain emanating from the diagonal wound in my low belly as my arms shook from the Percocets and I clung to the bassinet like a life raft. I marveled at my baby’s tiny brand-newness and resolved to keep my shit together for her. I should have been in bed resting, but instead, to prove I was a good mother, I pushed through my body’s pleas to slow down. This was my job now. I didn’t feel worthy of the title, but no one else could know that, so I faked it.

Eight hours prior, my baby was stuck in my pelvis and cut out of my stomach during an emergency C-section. Nurses handed her to me, and I held her on my chest and kissed her perfect bald head, and about an hour after we were brought to our room, I told my partner to go home. What was the point of Luke sleeping on the floor of a tiny, sweltering hospital room with paper-thin walls?

“Don’t worry. I can handle this,” I told him.

I was very high. I attempted to breastfeed my baby, and a kind nurse placed her in the bassinet and told me to get some sleep. Seconds, or minutes, or maybe an hour later, a different nurse shook my bone-weary body awake, threw off my blankets, handed me my baby, and told me to feed her. I didn’t want to cry, so I swallowed my tears along with the handful of painkillers and stool softeners she gave me. She also administered strict orders to pee, poop, and walk around as soon as possible, then she vanished. No one mentioned what was normal or what a body that was recently cut in half should feel like, so I did what I was told and forced my body to perform.

I shuffled by the rooms of my fellow C-sectioners and heard them moaning in their beds.

Didn’t they hear the nurses? We have to pee and walk around. Pretending to be fine was a part of me, and denying my pain was nothing new. My bodily experience came secondary to the front I’d been keeping up for my whole life.

My miraculous cesarean recovery performance was so convincing, the hospital released me less than forty-eight hours after giving birth, but my facade cracked when it hit me that I was in charge now. The nurse who brought over my discharge paperwork was met with the desperate face of a person who was not ready to be on her own and could no longer fake it when met with reality.

“I don’t feel ready to leave,” I cried, hunched over in pain, straining to comprehend the enormity of the task ahead of me.

“It’ll be okay,” she said sympathetically before adding: “We do need your bed for another patient.”

She walked out of the room, and I looked in the mirror.

Get it together, bitch. You’re a mom now. Ψ

Despite the self-hate that emerged as a survival mechanism in early motherhood, having a baby pushed me closer to the person I’d always wanted to be. Prepping for it while pregnant was the catalyst to getting and staying sober after two decades of on-and-off substance use.

Motherhood also made me determined to confront generational demons and raise my daughter differently than I was raised, to give her the gentleness, encouragement, and ease I wasn’t afforded. It’s a nice idea many new parents have, but one that I was comically unqualified to put into practice. It turns out, if you truly want to be kind and gentle with your kids, you must first learn how to be kind and gentle with yourself. I had to learn how, and I didn’t know where to start, so when my daughter was two, I began therapy.

After a month of weekly sessions, my therapist urged me to get assessed for ADHD. She suspected I had it, but my symptoms—trouble concentrating, feeling too damaged to fix, hypervigilance—also matched the profile for C-PTSD.

At the mention of ADHD, my mind went back to the nineties classrooms I longed to escape from, full of tween boys hawking spitballs past motivational posters with kittens on them. Those kids definitely had “ADD.” I was just a daydreamer back then, a hair-twirler who frequently forgot her textbooks at home and doodled endlessly on notebooks and desks. Surely, I had nothing in common with the hyperactive boys of my youth who ate glue for fun.

ADHD’s a disorder, like OCD,† that has become a part of our cultural lexicon, and one used as a personal punchline by many women trained to excuse themselves and apologize for living. When I heard I might have it, my first response was in line with this conditioning: “Well, doesn’t everyone have a little ADHD?”

No, it turns out.

ADHD is a brain disorder that affects approximately 2 to 4 percent of adults worldwide (although if we account for the undiagnosed, that number is likely much higher).

Once I became aware of adult ADHD, it was everywhere. The online tracking gods had my number, and social media fed me an endless supply of on-theme memes and TikTok videos. I could relate to the feelings of confusion, overwhelm, and shame people were depicting, but I still wasn’t convinced I could have it. I viewed ADHD as an excuse for being scattered and disorganized, and I wasn’t ready to excuse myself. Not yet.

My assessment with a psychiatrist was long and taxing, detailing the inner workings of my mind and my experience of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The report came back a week later, and I was officially diagnosed with ADHD at thirty-nine years old.

This happened one year into the pandemic, and I’m far from the only one who made this discovery about herself at that time. Memberships in the Attention Deficit Disorder Association (ADDA), an international nonprofit that serves adults with ADHD, nearly doubled between 2019 and 2021.* And worldwide Google searches for “ADHD women” started climbing in April 2020 and haven’t come back down since.

At the time, I didn’t even know what ADHD stood for, or at least what the H meant. It’s

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; however, most experts agree that the name is confusing. It might be better titled “attention malfunction disorder” or “restless mind syndrome” or “I’m definitely going to interrupt you but it’s not my fault.”

ADHD is a neurodevelopmental condition, or brain disorder. It impacts the

prefrontal cortex, and in case you didn’t pay attention in biology class either, that’s the organization and attention center of the brain. It also affects the

limbic system, which helps control emotions, memories, behavioral responses, and autonomic nervous system functions.

A 2006 study found that the cerebellum, the brain’s mover, shaker, and decision-maker, is the most “robustly deviant” region of ADHD brains.†3 The cerebellum, or “little brain” in Latin, is responsible for regulating our movements, controlling balance, and coordinating gait and muscle activity.4 Learning this gave me much relief because balance eludes me. I had BandAids on my knees for my entire childhood. I split my lip open twirling into an old wooden TV. I even lost my balance while dancing on a speaker in the club as a teenager and fell onto the concrete floor, knees first (they’ve never been the same).

The symptoms of ADHD usually first show up in early childhood and become more obvious as kids enter grade school. There is no biological test for it, and the diagnostic criteria, as we will learn, suffer from the pathological parameters of the

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM-5—the book many mental health professionals consult to identify the disorder. The criteria it lists are largely geared toward the

hyperactive, or typically young White male presentation. Some of the symptoms listed are:

- squirms when seated,

- fidgets,

- displays poor listening skills,

- sidetracked by external or unimportant stimuli,

- marked restlessness that is difficult to control,

- overly talkative,

- diminished attention span,

- interrupts, and

- impulsively blurts out answers before question is completed (my fave).

People aged seventeen and over need to have at least five symptoms for a diagnosis, while those under seventeen need six or more. These criteria are helpful, but they also leave out

a lot of the nuance that defines ADHD in girls and women.

Learning I have a neurological disorder that emerges in childhood baffled me at first. I showed many of the DSM symptoms, so how did no one notice it for over three decades?