Excerpt

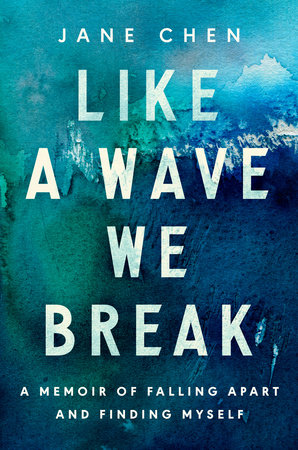

Like a Wave We Break

Chapter 1Genesis

The dining room was dim, the blinds half-drawn. My mother was dishing up a traditional Taiwanese dinner: a whole pan-fried fish, chicken with stir-fried vegetables, sauteed spinach, and egg-drop soup. She cooked like this every night. She placed the dishes on the table, then handed a plate of spaghetti and meatballs to Joyce. With a fork. Joyce grinned, pleased at her special treatment.

“Why does she get a fork?” I asked.

“Too little,” Mom said. Though what she really meant was too American. My older sister, Nancy, was eleven, and I was seven. We all used chopsticks, but Joyce, who was four, still hadn’t learned. I sat in my chair, one knee drawn to my chest, and started digging into my bowl of rice.

“Xiao Yu, don’t squat like that,” Mom scolded, calling me by my Taiwanese name. “You look like you sell vegetables at the outdoor market in Taiwan! What if you have dinner with a princess one day? You need to have good manners.”

After we finished eating, Mom stood to clear the dishes. Dad lit a cigarette and settled into his rust-colored La-Z-Boy in the living room. The familiar theme music of Wheel of Fortune played in the background as he grabbed the remote, turning the volume up.

“Our final puzzle is a person,” said Pat Sajak. “Lorraine, spin the wheel.”

Dad’s eyes glittered as the wheel slowed near $5,000. He loved the spin, the gamble, the moment that it might hit big. It clicked past, landing on $500.

“Agggghh!” Dad groaned.

“I’d like to buy a vowel, Pat,” said the contestant. “E.”

“Vanna, show us E.”

Vanna White floated across the screen in a sequined dress and flipped over a giant letter E.

Pat Sajak narrated the show, but my eyes were on Vanna, a live-action Barbie with perfectly coiffed golden hair, blue eyes, and what seemed like a permanent smile. If Vanna White was America, then I, with my black hair, brown eyes, and olive skin, most definitely was not.

Dad stared at the puzzle on the screen, brow furrowed.

“L,” said the contestant.

“L,” echoed Pat Sajak as Vanna began her strut. “There are four L’s.”

As Vanna flipped letters, Dad’s eyes flashed. Scanning back and forth over the puzzle, I could see him trying to spell the word, to piece it together. But with his limited English, he never could.

“You have $2,550,” Pat Sajak told the contestant. “Will you spin again?”

“No,” she said confidently. “I’m going to solve the puzzle.”

Dad pitched his body toward the screen, his eyes wide.

“Jolly good fellow!” said the woman.

“She’s got it!” Pat cried. Canned applause flooded the living room as Vanna revealed the rest of the puzzle. Watching the letters click into place, Dad’s face lit up, its soft wrinkles going taut.

“Zo Gao!” he exclaimed in Taiwanese, taking a deep, satisfied drag of his cigarette. Very good. So talented. I don’t think he knew what the phrase actually meant, but he was impressed when anyone solved the puzzle quickly. We passed most nights after dinner like this: Dad watching Vanna flip letters, while I added game-show phrases to my quickly growing vocabulary.

I was four years old when we immigrated to Southern California from Kaohsiung, a bustling port city on the southwestern tip of Taiwan. It was 1982, and Taiwan was still under one of the longest periods of martial law in history—and more than a decade away from its first open presidential election. Post-WWII, after fifty years of Japanese colonial rule, Taiwan was handed back to the Republic of China. A year later, civil war erupted on Mainland China between Mao Zedong’s Communist Party and the Nationalist Party, the Kuomintang (KMT). In 1949, the KMT lost the war and retreated to Taiwan, where it imposed a brutal one-party regime and placed the island under martial law for the next thirty-eight years.

The KMT ideology was to maintain power and crush dissent at all costs. As part of its anti-communist measures, free speech was curtailed and expression of Taiwanese national identity was restricted. Even publications in Taiwanese Hokkien—our native language—were banned. In what came to be known as “the White Terror,” the KMT imprisoned and murdered many of Taiwan’s intellectuals, artists, and social leaders in fear that they might resist the new rule. It’s estimated that more than 140,000 people were imprisoned during this time, and countless others were executed or disappeared. It was a surveillance state, an environment crackling with fear and paranoia.

A risk-taker with a restless spirit, my father sought autonomy in a place where autonomy could cost your life. A few years before I was born, he took a trip to the United States with his brother-in-law and came back electric with vision: we were going to immigrate to the Land of the Free. America represented modernity, opportunity, and freedom of thought. People in Taiwan coveted anything American, from soap to refrigerators. All the best cinema and music came from America. Mom’s favorite actress was Elizabeth Taylor. She loved listening to The Carpenters and watching movies like Roman Holiday and Giant. Plus, two of Mom’s sisters were already living in California. One of Dad’s was there as well. America was going to be Dad’s fresh start.

Mom was amenable to the plan, though really she had no concept of how far away America was—geographically or culturally. Or what she’d do when we got there. She didn’t ask those sorts of questions. My mother had been raised to believe that the best thing that could happen to her was to find a good husband. So, when Dad said they were moving, she trusted him implicitly. Not because he’d earned it, but because he was the man.

Like most couples in Taiwan in the 1970s, my parents had an arranged marriage. Matches were mostly based on socioeconomic status, and the fact that my grandfathers on both sides were respected doctors made my parents an appropriate pairing. Dad was working as an engineer at a plastics company. He had a good job and a pleasant demeanor, and after asking around town, Mom’s family found no evidence that he was either of the two things they believed a husband should never be—a drinker or a gambler.

My parents met only twice before their engagement. Once with all four parents, and once, alone, for dinner. Three months passed between the dinner and the engagement, which my grandfather agreed to on my mother’s behalf.

“Why didn’t you ask me?” she demanded when she found out.

“You didn’t say you disliked him,” her father replied.

Her silence was consent enough. After their wedding, Dad was promoted to a managerial role at the plastics company and they moved to Taipei, where Mom got pregnant with Nancy, my older sister. Dad’s father passed away soon after, so my dad quit his job and my parents moved back to Kaohsiung. Dad decided to dabble in something new and started a construction company. It kept him busy for a while, but his sights were already set on something bigger.

Dad started the green card application process shortly before I was born in 1978. Ten days after my birthday, Jimmy Carter announced that the United States would sever diplomatic relations with Taiwan and establish official relations with the People’s Republic of China. “There is but one China and Taiwan is a part of China,” he said, echoing the position that more than fifty other countries had already adopted. Carter’s announcement was a huge blow to Taiwan’s international standing and hope for independence. In the wake of this policy, immigration processing in the United States for Taiwanese nationals slowed significantly. The fear of a full communist takeover loomed.

By the time our green cards finally came through, Nancy was eight, I was four, and our baby sister, Joyce, was one. Dad really wanted a boy, but as luck would have it, he had three girls. He didn’t tell anyone we were leaving Taiwan until the week before our departure. Even though emigration was legal, the political situation was volatile, and he was paranoid about being detained or questioned. Mom set out packing, trying to shrink our entire lives into two massive army duffels. There was room for only the essentials, Dad said, which included an entire set of dishware and the rice cooker. On his first trip to America, he’d confirmed that there was rice, so he was more comfortable about the move. No rice, no life! Mom was relieved she wouldn’t have to pack that too.