Excerpt

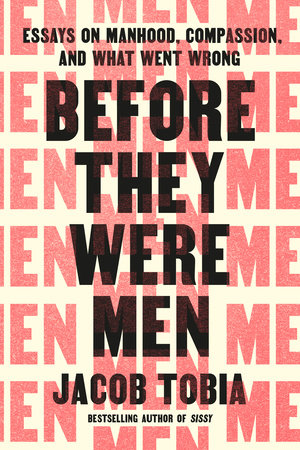

Before They Were Men

IntroductionTo the Boys in the BackThey just sat there. Staring down at their desks, eyes blank, they barely seemed to move. It would’ve been easier if they’d lashed out, if they’d tried to spar with me, if they’d made some attempt to derail the class, but no.

Roll your eyes, I thought to myself.

Smack your lips in contempt. Suck your teeth. Laugh cruelly under your breath. Whisper something awful or pass a nasty little note. Ask an aggressive, insulting question, maybe. Something. Anything. I dare you.Nothing.

For almost an hour, they sat there—detached, deflecting, disengaged—and as they sat, I crumbled. They broke me, those two boys. Split me in half. Their silence and disconnection, the stoicism, the quietude in the face of trauma, the apparent lack of any feeling at all. It ripped me up, not because of my pain, but because of

theirs. Frankly, they exuded the stuff. It was everywhere.

Bearing witness to it was grisly, but as I stood in front of the class in a cheap, glorious faux- flapper dress and sparkly Chucks, I tried not to show it. I had a job to do.

. . .

It was the fall, and at long last, after two years of virtually no outside speakers allowed on university campuses due to pandemic restrictions, I was guest lecturing at Santa Monica College. I cannot emphasize enough just how much I love speaking at schools. Each time I take to the stage or the podium, I get to be the quirky, hot, fashionable professor I was born to be—the edgy gender studies department chair I probably would’ve become if my life’s course had been altered by a millimeter or two. I put on a skimpy dress, a hyperpigmented lip, and a pair of chunky clip-ons and strut to the front of the room with the power femme authority of my dreams. And then, for an hour or so, I celebrate and entertain and mourn and cry and giggle about gender alongside young people who are the future of everything we know.

It’s a mutual process, the secret being that I get every bit as much out of speaking to students as they get out of listening to me. If I’m being honest, I might get even more out of it than they do. Yes, they’re afforded the chance to listen to a hairy nonbinary lady wax poetic about queerness and the state of the trans movement, but I receive something much greater in return: an abiding faith in the future of this world. As I share an hour with them, I learn what young people are thinking, hear what they’re talking about, and leave knowing that this particular culture war is already being won. That, at least in terms of gender and sexuality, this world is headed somewhere amazing. The fact that I am often paid to do so is beyond me. Truth be told, I’d give keynotes for free, out of sheer bliss, if for no other reason than to give the sequins in my closet and the sequins in my heart more opportunities to shimmer for others.

This day was no different. I’d already given my keynote lecture in anauditorium across campus, and following a swig of coffee and a quick strut across the quad, I was now leading an undergrad queer studies class in a forty-five-minute workshop entitled Gender and Memoir.

I began the class as I always do, by reading excerpts from one of my books. Story time.

Being read to is highly underrated. You’d assume it’d be boring, but people love it. They feel like kindergartners again, and I transform into their trans Ms. Frizzle–esque kindergarten librarian, complete with a nineties geometric-print dress. When it comes to gender, a system of power and identity that’s been instilled in most of us from before we were even born, I find that being read to gives rise to exactly the type of child mind required to see things with fresh eyes. It’s my belief that if you learned something when you were three years old, you should return to your three-year-old mind in order to unlearn it.

For that day’s readings, I focused on moments of gender challenge and gender joy. Instead of standing behind the podium like a respectable transvestite, I popped up onto a table at the front of the classroom and read from there.

I started by sharing a story about the time my brother and his friends found my Barbie, cut off all her hair, and hung her in effigy from the banister in my childhood home. It’s not a light note to begin on; it’s a heavy story that lands at a pivotal symbolic moment. Because, of course, my brother and his friends weren’t really hanging

my Barbie in effigy; they were hanging

my femininity. They weren’t symbolically killing her; they were symbolically killing

a part of me. Understandably, most people in the room were quiet.

But then I moved along to a story all about the ways that, in contradiction to everything you might think, church was one of the only places I found gender safety as a child. At church, I was allowed to be a glorious little queen because my enthusiasm for performance and crafts and fagging out was always misconstrued as enthusiasm for my personal lord and savior, Jesus Christ. Singing in church, performing in musicals, excelling at art, and wearing flowy acolyte robes that were basically dresses didn’t make me gay, darling: they made me a good lil’ Christian boy.

That reading did the trick. By the time I got to the sentence “Yes, I may have been queening out in the church musical, but I was queening out

for Jesus, so it was fine,” the mood in the room had become one of jovial, blasphemous, sacred laughter.

It was then that I first noticed them, the boys in the back. They hadn’t laughed once, let alone smiled. For the most part, they hadn’t even been able to look at me. Eyes glued to the floor, they simply sat. I made a quick mental note of that, concerned by their emotional shutdown, but I had to keep moving. It didn’t feel appropriate to stop the whole lecture and say, “Hey, you two dudes who’re clearly not listening and have decided not to participate, are you okay and can we get you a therapist?” in front of everyone.

I proceeded to give the class their first assignment: take five minutes to yourself and reflect on moments of gender challenge and joy from your own life, ones that you think would make for compelling memoiristic essays. “Try to think outside the box,” I told them. “Find stories that transcend the normative ways we’re taught to talk about gender. Stories that are unexpected or surprising, that take a small detail and spin it into a web of meaning. Don’t hold yourself back or be afraid to really go there.”

(It’s an activity that you, dear reader, might want to consider doing yourself.)

I set a five-minute timer on my phone, and we were off: they dutifully journaled to themselves as I dutifully scrolled through memes on my phone. Two minutes and three pictures of silly cats in, I looked up. Most students were sitting quietly, scribbling down notes, lost in reflection.

But not the boys in the back. One was on his phone. The other was picking at his notebook.

That’s okay, I thought.

It doesn’t mean they aren’t engaged. Thinking looks different for different people. Some people chew their nails or a pencil. Others tap their feet or doodle until

inspiration strikes. I pull the hairs out of my eyebrows and gaze aimlessly around the room.

After five minutes were through, I told everyone to form small groups and share the memories that had come to mind. I set another timer, this one for seven minutes, and sat back, basking in the cacophony of voices that sprang forth the moment I said, “Go.” Nothing makes for a happier teacher than a loud room of enthusiastic students. I scrolled through a few more memes on my phone, sent a quick email or two, then got up to check in with the professor and confirm that we were still on schedule.

I surveyed the classroom again. It was buzzing. You could track the flow of individual conversations as each group oscillated between compassionate listening and raucous giggles. I drank it all in: a room full of thirty young people thinking critically about their experience with gender, sharing with one another in the discoveries they were making, dusting off memories until they sparkled again, and getting academic credit for it? Pinch me. It was one of those apex moments in life when you’re able to see in real time the impact you’re having, where you can witness, firsthand, the effect of your life’s work.

Then I glanced over at the boys in the back, and it all came crashing down. As the rest of the room hummed with energy, they slouched in their chairs, doing absolutely nothing. Although they were sitting directly next to each other, not a single word passed between them. The contrast was unsettling: like looking at a photograph of a group of smiling children only to realize, upon closer inspection, that one kid in the back is just standing there, staring off. It’d be less alarming if the kid were crying or seemed angry, because at least then there’s a story: he was having a bad day, he didn’t want to be in the picture, he didn’t feel like smiling and let everyone know. He cried out or screamed or scowled and made his displeasure known.