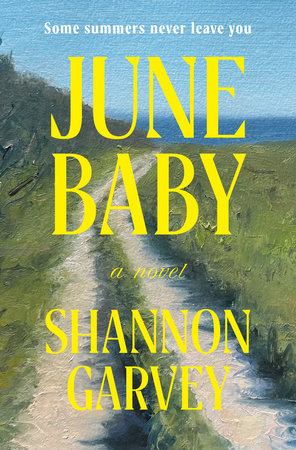

Excerpt

Laws of Love and Logic

Portsmouth, Rhode IslandSeptember 1976Early fall. Leaves of gold on the birch shimmered when the wind picked up. When no one answered the front door, Lily walked around the side of the house to the back deck. She could hear her boyfriend’s father playing guitar and singing softly, a melancholy tune—familiar, but she couldn’t quite make it out. The boy, like his dad, was musically inclined. Playing the guitar had a calming effect on Mr. Cooper, especially after his son’s football games.

The back deck was unfinished, littered with tools and cans of paint with rusted lids—neglected since last spring—alongside a spare tire, two fishing rods, and a cooler. The boy’s dad was on his seventh beer; by the time the day was over he would have finished off a case by himself. Lily didn’t want to disturb Mr. Cooper and waited until he looked up from his guitar.

“There’s my favorite girl,” he said with a big smile, resting his forearm on the body of the instrument.

“Don’t stop on account of me,” Lily said. “I love hearing you play.”

Mr. Cooper, still smiling, shook his head and leaned his guitar against a post on the deck.

“Some game, huh?” he said as he stood up.

He offered Lily his seat, the only one on the deck: a mustard-and-orange-webbed aluminum lawn chair. When she refused to sit, he remained standing.

It had been an exciting game that morning: Portsmouth against Barrington, rival teams. The boy, a senior at Portsmouth and the team’s quarterback, had read the defenses instantly, successfully changing the play at the line of scrimmage three times when Barrington’s defense had anticipated Portsmouth’s plays and was prepared to stop them.

When the boy appeared at the screen door in a pair of jeans and a Creedence Clearwater Revival T-shirt, toweling off his long brown hair, his dad couldn’t contain himself and gave the boy a hug, patting his back.

“Four hundred and ninety passing yards! That’s a record. One game! That’s my boy!” Mr. Cooper was smiling from ear to ear, so excited that he spat as he talked.

The boy watched Lily. She never seemed to mind that his father always drank and talked endlessly about the boy’s football stats.

“Everybody knows he’s the best the state has ever seen. When he was fourteen and there were sixty seconds left on the clock, he threw the ball fifty yards and that Portuguese kid caught it.”

“Lil knows the story,” the boy said, putting his arm around his dad. He was tall like his father but a whole lot bigger.

“I was there, Mr. Cooper—I saw the whole thing. Just like Roger Staubach!”

“Marry this girl!” the boy’s father said. He took a long swig of his beer.

The boy knew that over the past five decades, the little state of Rhode Island had produced three professional quarterbacks; he was determined to be the fourth. He was ten years old when Joe Namath predicted that the Jets would beat the Colts in the 1969 Super Bowl. As a young kid, the boy had borrowed Namath’s courage and boldness. Sometimes, standing in the locker room in front of his teammates, he would say, “We’re going to win this one, I guarantee it.”

The boy took Lily’s hand, led her inside, and pulled the screen door shut behind him. He took two beers out of the refrigerator, and as he and Lily made their way downstairs to the basement, they heard his father: “Chuck at the hardware store said that the scouts will be coming around to have a look at you!”

When the boy was six, his mom took off and moved to Florida with the golf pro from Green Valley golf course. For Christmases and birthdays, she sent her son cards. The boy had learned that his mother was playing piano in a bar in Boca Raton. Back then no one had ever heard of Boca Raton but the boy found it on a map when he was in the second grade. Folks in town heard that the golf pro hit her occasionally and got one of the waitresses pregnant at the resort where he worked.

Every trophy the boy had ever won was displayed on the wooden shelves his father made for him. While football was his main sport, he also played basketball and baseball. The largest trophy was the one he’d received the prior year for football: MVP, a pewter sculpted figure—poised to throw a football—mounted on a wooden base. Free weights and a bench filled one side of the boy’s basement room, with a bed, a TV, a set of drawers, and an old electric keyboard on the other side. In the corner was a brand-new Sony stereo, which his father had recently bought him for his eighteenth birthday. Albums were carefully lined up between two cinder blocks.

Lily placed her beer near a stack of library books on the chest of drawers and picked up the boy’s sunglasses. Putting them on, she stretched out on his bed. The boy sat down at the keyboard.

“Did I ever tell you that my mom played the organ at Saint Barnabas and that’s where she met my dad?”

Lily turned her head on the pillow to watch him. He had told her this, but she didn’t mind hearing it again, not in the least. “Tell me” was all she said.

“He fell in love with her on a Sunday in between the Gloria and Communion.”

“That’s beautiful.”

“After my mom left, he just couldn’t go back there, so that’s why we go to Saint Anthony’s. I can remember our last Christmas together. Although, I didn’t know it would be our last. She played ‘O Holy Night’ at Mass. I was real sad watching my dad cry.”

Lily swung her legs over the side of the bed and sat up. Before she could say anything, he changed the subject and said, “Do you know this song?”

His hands moved tentatively across the black and white keys. Like birds pecking in the sand, his fingers bent lightly. He started and stopped a couple of times, but when he was able to pull it together, combining the chords with the right individual notes, Lily exclaimed, “How did you learn that?”

A little soft, but melodic, the boy sang: “

The screen door slams, Mary’s dress sways / Like a vision she dances . . . ”

As the boy worked out the chords to “Thunder Road,” Lily slipped her hand under his shirt and caressed his back.

Born to Run was released the year before, and Lily and the boy both unknowingly bought the other the album for Christmas. The boy stopped playing and looked up at Lily. “That’s as far as I’ve gotten.”

“Call in sick tonight,” Lily said.

“I can’t. You know that.”

“What’s a party without the team quarterback?”

“Are you still planning on going?”

When Lily didn’t answer, the boy rose from the keyboard bench and moved over to his bed. He worked Saturday and Sunday nights, but never Fridays, not the night before a game. He washed dishes at Reidy’s diner on East Main Road. Late into the shift, when it was just the owner and the boy, the owner would fill Styrofoam containers with mashed potatoes, green beans, and meat loaf. The Saturday night special. He’d always add a couple of desserts, one for the boy and one for his father.

The boy sat on the edge of his bed. Lily followed him. She got down on her knees and wiggled herself in between his thighs.

“I promise you’ll have a good time,” Lily said.

She and the boy had been together since they were freshmen, and while they had yet to have sex, they delighted in each other’s caresses with hands and mouths, here in the basement or in the field behind the school. With the tip of her finger, Lily moved a strand of her hair away from her face.

“I don’t understand why you want to go to the party without me,” the boy said.

“Am I supposed to sit home every Saturday night my senior year because you have to work?”

The boy looked away.

“I’m sorry,” she added.

And she was. She knew the boy helped his father out with the basic bills: electricity, groceries, and sometimes the oil bill when the winters were at their worst. The boy had his first job when he was thirteen, a paper route. The factory in Fall River, where his father had worked for fifteen years and planned on working for the rest of his life, had closed down. Now his father earned a living working at one of the marinas on the island. Like many working-class kids, the boy was coming of age in a time of great economic anxiety.

“I’ll go with Jane,” Lily said.

“Yeah? And by ten o’clock either you’ll be holding her hair back while she’s puking or she’ll be upstairs in one of the bedrooms with Jimmy Sullivan or some other guy she barely knows.”

“That’s my sister you’re talking about. And what difference does it make who she’s in a bedroom with?”

The boy knew that Lily would go to the party without him. He couldn’t help but feel jealous, so much so that he decided not to tell her what he had been holding in all afternoon—something he hadn’t even shared with his father: There had been scouts at the game today. He would tell her tomorrow. After the party.