Excerpt

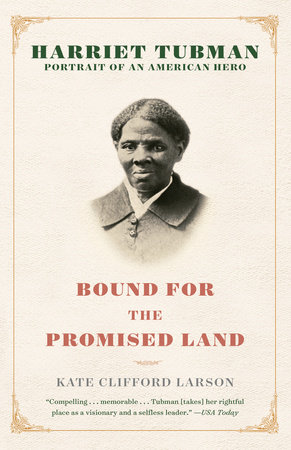

Bound for the Promised Land

CHAPTER 1

LIFE ON THE CHESAPEAKE IN BLACK AND WHITE When Harriet Tubman fled her dead master’s family in 1849, she was not the only slave from the Eastern Shore of Maryland racing for liberty. In 1850 a total of 279 runaway slaves earned Maryland the dubious distinction of leading the slave states in successfully executed escapes. The motivations for running away are no mystery; however, in many cases the methods of escape remain unknown even to this day. Despite stepped-up efforts in Maryland and other southern states to thwart escapes during the ten years before the Civil War, some slaves did marshal the strength and courage to take their liberty. But few returned to the land of their enslavers, risking capture and reenslavement, even lynching, to help others seek their own emancipation.

How did Tubman successfully escape bondage in Dorchester County, and how did she manage to return many times to lead out family and friends? Not merely the recipient of white abolitionist support, Tubman was the beneficiary of, and a participant in, an African American community that challenged the control of white Marylanders, from the earliest Africans brought from Africa to the outbreak of the Civil War.

Tubman’s story begins several decades before her birth with a complicated set of interrelationships, black and white, enslaved and free, of several generations of families living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. As historian Mechal Sobel describes it, this was a “world they made together.”

Dorchester County lies between two rivers, the Choptank to the north and the Nanticoke to the south and east, and extends from the Chesapeake Bay to the Delaware state line, encompassing almost 400,000 acres of dense forest full of oak, hickory, pine, walnut, and sweet gum; marshes and waterways; and extensive farmland. Numerous navigable rivers and creeks crisscross the county, offering access to trade and suitable sites for shipbuilding. The flat terrain provides abundant tillable lands for tobacco, wheat, corn, fruit, and other agricultural products, and before modern times, the vast supply of oyster shells helped keep soils fertile.

The Choptank River rises near the Delaware line, flowing south between Caroline and Talbot Counties and on to Dorchester County, finally emptying into the Chesapeake. In the nineteenth century, the river remained navigable for nearly forty miles upstream from the Chesapeake Bay. Dorchester’s southern border, the Nanticoke River, was navigable throughout its course from Seaford, Delaware, to the Chesapeake; the town of Vienna served as its port of entry and be- came a major trading center during the early nineteenth century, providing bay access to neighboring Somerset County and southwestern Delaware.

It was to this landscape that Harriet Tubman’s African ancestors were forcibly brought to labor in servitude to white masters. Enslavement of Africans in Maryland, and the laws and regulations that codified slavery’s existence, evolved slowly over a hundred-year period. Until the early eighteenth century white indentured servitude was common, particularly on the Eastern Shore. Some planters had both slaves and indentured servants; by the 1730s and 1740s, however, shipments of black captives from Africa to the Americas had increased dramatically. Numerous laws were enacted relating to ownership of slaves, including ones specifying that any children born to an enslaved woman would carry the status of the mother, with ownership remaining with the slave woman’s owner, even if the father was a free black or a white man.

Thus Tubman’s story begins with the history of some of the white families who claimed ownership of her and her family. The detailed records of the lives of the white families who enslaved Tubman, her family, and her friends, demonstrate the sharp contrast between the lives of whites and blacks, lives intimately entwined yet irreconcilably different. Following these white families’ lives as closely as the remaining records allow reveals the lives of their enslaved people, bringing to life the web of community into which Tubman was born. The white Pattisons, the Thompsons, the Stewarts, and the Brodesses played key roles in the lives of Tubman’s family. On the Eastern Shore of Maryland, most black people, slave and free alike, moved around according to the land ownership patterns, occupational choices, and living arrangements of the region’s white families. Out of necessity, many black families maintained familial and community ties throughout a wide geographic area. Family separations were not always precipitated by sale; some whites owned (or rented) land and farms across great distances, requiring a shifting of their enslaved and hired black labor force at varying times throughout the year, or at various times over a period of decades when new land had been purchased and the cycle of clearing and es- tablishing new farms began. This pattern of intraregional movement forced families and friends (both black and white) to create communication and travel networks in order to maintain ties with family and community. These complicated networks made it possible for Tubman to become one of the rare individuals capable of executing successful and daring rescues repeatedly.

A devastating fire at the Dorchester County courthouse, set by an unknown arsonist in May 1852, destroyed a great portion of Dorchester County’s historical records. Because few records survived from before 1852, piecing together the nature of black and white relationships in Dorchester County can be done in only a limited way. For instance, we do not know the names of all the slaves owned by Edward Brodess, Harriet Tubman’s owner, nor all of those owned by Anthony Thompson, the owner of Tubman’s father, Ben Ross, from the first half of the nineteenth century.

Several documents did survive the fire: the records of the Orphans Court from 1847 to 1852 were saved because the clerk of the court brought the logbook home to work on it over the weekend. This quirk of fate secured a five-year segment of history important to revealing details of Tubman’s life and of those black and white families who were part of her community. Other records were saved, too: the books listing manumissions, freedom papers, and many chattel records (where slave sales were recorded) were preserved, providing important information about the black community and vital genealogical data for many families in the area. District court cases, heard at the appeals court located in neighboring Talbot County, were recorded at the state level, as were most land transactions, thereby preserving some information from the colonial era and the early republic. Fortunately, these court records contain some of the most dramatic documentation available detailing Harriet Tubman’s life in slavery.

Reaching Beyond the Grave: The Legacy of a PatriarchIn 1791 Atthow Pattison, the patriarch of a long-established Eastern Shore family, sat down to contemplate his legacy to his children and grandchildren. A Revolutionary War veteran, a modest farmer, and an even more modest slaveholder, Pattison could proudly trace his roots in Dorchester County back at least a century. Intermarrying for generations, the Pattisons and other Eastern Shore families consolidated their control over vast tracts of dense timberland, rich marshlands, and productive farms.

Standing at his front door, Pattison could view much of his approximately 265-acre farm, situated on the east side of the Little Blackwater River, near its confluence with the larger Blackwater River. From the wharf in front of his home Pattison probably shipped tobacco, timber, and grain, destined for England and other markets, and received goods originating from the West Indies or England as well as other trading points in New England and along the Chesapeake.

After dividing tracts of land, including his home plantation, and arranging for payments to his grandchildren when they came of age, Atthow bequeathed his remaining slaves and livestock to his surviving daughter, Elizabeth, and her children, Gourney Crow, James, Elizabeth, Achsah, and Mary Pattison, and to his son-in-law, Ezekiel Keene, and his children, Samuel and Anna Keene. Elizabeth, in keeping with her father’s implicit understanding that his children marry “in the family,” had married her cousin William Pattison, and they lived on a nearby plantation. Atthow’s second daughter, Mary, had married her cousin Ezekiel Keene and moved to a farm south of Atthow’s land, though she was dead by the time the will was written.

When Atthow Pattison died in January 1797 he gave to his granddaughter Mary Pattison one enslaved girl named “Rittia and her increase until she and they arrive to forty five years of age.” This phrase, limiting Rit’s and her children’s terms of service to forty-five years, provided for Rit’s eventual manumission, or freedom, from slavery. Maryland manumissions had taken place even in the earliest days of slavery. Never an informal procedure, manumissions were taken quite seriously and were often recorded in land records (as deeds) for each county. Some slaves were able to earn enough money to buy their own freedom, and on occasion slaves sued for their freedom, some eventually prevailing. In 1752 Maryland passed a law restricting manumission by will to slaves “sound in body and mind, capable of labor and not over fifty years of age,” so as to prevent slaveholders or estates from avoiding responsibility for the care and maintenance of “disabled and superannuated slaves.” Manumitting slaves was illegal if the grant of manumission was written in part “during the last fatal illness of the master,” or if the freeing of slaves affected the ability of creditors to settle their claims against the estate of the deceased. This legislation, it was hoped, would slow the increasing number of deathbed manumissions and hold slaveholders more accountable for the support and maintenance of indigent slaves.

Limiting Rit’s term of service lowered her market value to Pattison’s heirs if they were inclined to sell her after gaining possession of her. No doubt Pattison was aware of this, but he may have been influenced by the spirit of the times. On the Eastern Shore, as elsewhere in the new nation, a complex movement was emerging, both religious and secular, that spurred a marked increase in manumissions during the 1790s. While elite families still maintained much control, wealth could be achieved readily with the expanding production of wheat and other grains for export markets, providing viable roads to prosperity for entrepreneurial families in Dorchester and the surrounding counties. The rise of intensive grain agriculture and timber harvesting transformed work patterns on the Eastern Shore. Tobacco production required a year-round labor force, but grain agriculture did not. While timber harvesting could be carried on throughout the year, it also required continuous acquisition of land once one lot had been cut, and it demanded a predominantly male labor force. These factors, among others, altered the nature of black slavery and freedom on the Eastern Shore by 1800; on one hand, free black labor became, to some extent, a more attractive economic alternative to owning slaves, while on the other hand, some white slaveholders found it lucrative to sell off their excess slaves.