Excerpt

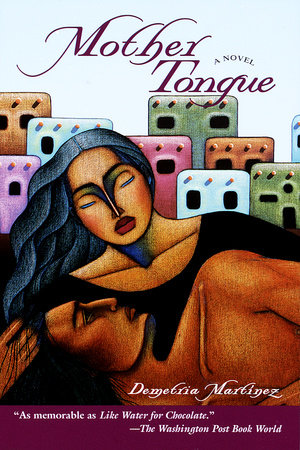

Mother Tongue

Remember us after we are gone. Don’t forget us. Conjure up our faces and our words. Our image will be as a tear in the hearts of those who want to remember us.

—POPOL VUH, MAYAN SCRIPTURES

This is the story of how we begin to remember This is the powerful pulsing of love in the vein

—PAUL SIMON, “UNDER AFRICAN SKIES

One

His nation chewed him up and spat him out like a piñon shell, and when he emerged from an airplane one late afternoon, I knew I would one day make love with him. He had arrived in Albuquerque to start life over, or at least sidestep death, on this husk of red earth, this Nuevo Mejico. His was a face I’d seen in a dream. A face with no borders: Tibetan eyelids, Spanish hazel irises, Mayan cheekbones dovetailing delicately as matchsticks. I don’t know why I had expected Olmec: African features and a warrior’s helmet as in those sculpted basalt heads, big as boulders, strewn on their cheeks in Mesoamerican jungles. No, he had no warrior’s face. Because the war was still inside him. Time had not yet leached its poisons to his surfaces. And I was one of those women whose fate is to take a war out of a man, or at least imagine she is doing so, like prostitutes once upon a time who gave themselves in temples to returning soldiers. Before he appeared at the airport gate, I had no clue such a place existed inside of me. But then it opened up like an unexpected courtyard that teases dreamers with sunlight, bougainvillea, terra-cotta pots blooming marigolds.

It was Independence Day, 1982. Last off the plane, he wore jeans, shirt, and tie, the first of many disguises. The church people in Mexico must have told him to look for a woman with a bracelet made of turquoise stones because he walked toward me. And as we shook hands, I saw everything—all that was meant to be or never meant to be, but that I would make happen by taking reality in my hands and bending it like a willow branch. I saw myself whispering his false name by the flame of my Guadalupe candle, the two of us in a whorl of India bedspread, Salvation Army mattresses heaped on floorboards, adobe walls painted Juárez blue. Before his arrival the chaos of my life had no axis about which to spin. Now I had a center. A center so far away from God that I asked forgiveness in advance, remembering words I’d read somewhere, words from the mouth of Ishtar: A prostitute compassionate am I.

July 3, 1982

Dear Mary,

I’ve got a lot to pack, so I have to type quickly. My El Paso contact arranged for our guest to fly out on AmeriAir. He should be arriving around 4 p.m. tomorrow. As I told you last week, don’t forget to take the Yale sweatshirt I gave you just in case his clothing is too suspicious looking. Send him to the nearest bathroom if this is the case. The Border Patrol looks for “un-American” clothing. I remember the time they even checked out a woman’s blouse tag right there in the airport—“Hecho en El Salvador.” It took us another year and the grace of God to get her back up after she was deported.

Anyhow, when he comes off the plane, speak to him in English. Tell him all about how “the relatives” are doing. When you’re safely out of earshot of anyone remind him that if anyone asks, he should say he’s from Juárez. If he should be deported, we want immigration to have no question he is from Mexico. It’ll be easier to fetch him from there than from a Salvadoran graveyard. Later on it might be helpful to show him a map of Mexico. Make him memorize the capital and the names of states. And I have a tape of the national anthem. These are the kinds of crazy things la migra asks about when they think they have a Central American. (Oh yes, and if his hair is too long, get him to Sandoval’s on Second Street. The barber won’t charge or ask questions.) El Paso called last night and said he should change his first name again, something different from what’s on the plane ticket. Tend to this when you get home.

I’ve left the keys between the bottom pods of the red chile ristra near my side door. Make yourselves at home (and water my plants, please). I’ve lined up volunteers to get our guest to a doctor, lawyers, and so forth for as long as I’m here in Arizona. God willing, the affidavit from the San Salvador archdiocese doctor will be dropped off at the house by a member of the Guadalupe parish delegation that was just there. That is, assuming the doctor is not among those mowed down last week in La Cruz.

As I told you earlier, our guest is a classic political asylum case, assuming he decides to apply. Complete with proof of torture. Although even then he has only a two percent chance of being accepted by the United States. El Salvador’s leaders may be butchers, but they’re butchering on behalf of democracy so our government refuses to admit anything might be wrong. Now I know St. Paul says we’re supposed to pray for our leaders and I do, but not without first fantasizing about lining them up and shooting them.

Now see, you got me going again. Anyway, we used to marry off the worst cases, for the piece of paper, so they could apply for residency and a work permit. But nowadays, you can’t apply for anything unless you’ve been married for several years and immigration is satisfied that the marriage is for real. Years ago, when Carlos applied, immigration interrogated us in separate rooms about the color of our bathroom tile, the dog food brand we bought, when we last did you-know-what. To see if our answers matched. Those years I was “married” I even managed to fool you. That is, until we got the divorce, the day after he got his citizenship papers. But you were too young for me to teach you about life outside the law. Which used to be so simple in the old days.

Failing everything, we’ll get the underground railroad in place. Canada.

Thanks, mijita, for agreeing to do this. The volunteers will take care of everything (they know where the key is hidden), so just make our guest feel at home. Maybe take him to Old Town. After all, it’s not everyone who lives on a plaza their great-great-etcetera-grandparents helped build. I’m glad you have some time, that you’re between jobs. With your little inheritance, you can afford to take a few months off and figure out what to do with your life. But don’t get yourself sick over it. I’m fifty and I still haven’t figured it out for myself. Just trust the Lord, who works in mysterious ways.

I don’t know how long I’ll be in Phoenix. My mother’s last fall was a pretty hard one, and if she needs surgery, I could end up here for the summer. Don’t forget to feed the cats and take out the garbage. I’m slipping this under your door so that if they ever catch me, I won’t have conspiratorial use of the mails added to all the other charges I’ve chalked up. Rip this up! Be careful.

Love & Prayers,

Soledad

P.S.: Take it from one who survived the ’60s. Assume the phone is tapped until proved otherwise.

P.S. #2: And don’t go falling in love.