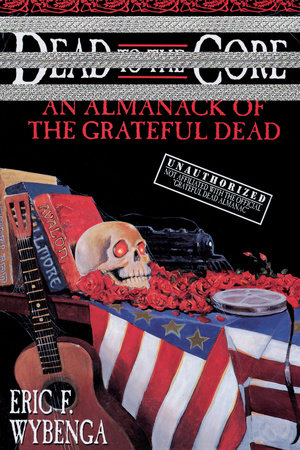

Excerpt

Dead to the Core

We begin with the inescapable It. Jerry is gone, and there will be no more Grateful Dead shows. There will come a time when these sad facts no longer bear mentioning, and already their effect upon those of us who call ourselves Deadheads has changed. The character of Deadheads' mourning has subtly shifted from head-shaking wordlessness to a grim acceptance of simple truth. Even an accepted truth can surprise people, though, such as when the hankering for a show bubbles up from the unconscious or when they are confronted with images captured on video.

Jerry Garcia was not a saint, a fact that we have been acquainted with amply in the stories and books that have followed in the wake of his passing. But he was a pretty damn fine example of a human being. One gets the feeling that he was a man possessed of such boundless creative and interpretive power that he would have left his mark on any field of artistic endeavor he chose. As such, music was lucky to have had him, especially given the young Garcia's struggles with whether to follow the muse of visual art or music. I suspect that in an odd little corner of the Eep dimension, there once lived a painter by the name of Jerome J. Garcia, an artist whose canvases bore the mark of brushstrokes both obsessively fine and audaciously broad, whose palette played host to colors of his own invention, whose work encompassed the fiercest strains of abstract expressionism and the humblest folk art, an artist who sent people home from galleries weeping and laughing over small works of portraiture that perfectly captured their subjects' essence yet reserved for them the personal mystery at the heart of verisimilitude. This Se±or Garcia, beloved of many, would for his personal amusement pick up a guitar from time to time. Those who were lucky enough to behold the fruits of his avocation commented on how closely his music matched the restless wit evinced in his better-known paintings.

Of course,

our Jerry Garcia chose guitar over paintbrush, and his life's work would fill a very large canvas indeed. Because he chose the supremely expressive medium of music, he has touched us all. One can argue endlessly and pointlessly about the technical merits of Jerry's guitar playing, but one thing on which all seem able to agree is that his playing possessed an almost matchless ability to convey emotion and mood. The same is true of his voice, though this quality in his performances often goes unheralded. In Jerry's homespun blend of vocal styles--a bit of Bill Monroe, a little Bob Dylan, a pinch of Lennon

and McCartney--he created for himself a voice of unforced affect. His interpretive talent--which sprang from the same nook of his creative mind whence came all those eloquent guitar phrasings--was such that he seemed to live so many of his songs rather than simply emote them. In later years, his voice raspy and weathered, singing as he always has at the upper limits of his range (and always, no matter how shot the voice, on key), he became in performance the very personification of the wisdom of years. The plainspoken honesty of his playing and singing, coupled with the wit and intellectual playfulness we saw in interviews, made us feel not only as if we knew him but that he was someone very special to know.

Jerry and the Dead are sorely missed and will continue to be, with all those shows unplayed and songs left unwritten (or at least uncovered!). And we also feel the loss of the total experience of touring and the shows themselves. But we also miss the personality of the Dead, for they were a band that possessed this in abundance. This character wasn't always good or kind or happy, and that's just the point. Here was a band that was remarkably honest in how they allowed us to see them. Because of this unwillingness to construct elaborate facades in performance and life, they became a part of our lives, our friends, the Boys, who really knew how to play music. This gave the music and the band's history a living drama, a vibrancy, it might not otherwise have possessed ("Listen to that solo--you can tell Jerry's pissed at Weir for blowing the verse"). It is in a sense ironic that we call Dead concerts "shows" because compared with most rock bands there was very little "show" at all. There was instead music played by interesting people with a fantastic history.

What a history! There are so many facts of the Grateful Dead's life, both happy and sad, that could not have been more perfect if they had been scripted--that they were the house band at the Merry Pranksters' Acid Tests; that both Robert Hunter and Ken Kesey were turned on to acid while acting as guinea pigs for government-sponsored LSD studies, then went on to play a large role in inventing the cultural component of what we now think of as the sixties; that the Dead's earliest patron and benefactor was Augustus Owsley Stanley III, aka Bear, the sixties' most legendary tabber of acid; that this band of misfits and their benefactor would essentially invent the modern rock sound system; that the Holy Grail of Dead tunes, Dark Star, would be the first tune that the Dead and Hunter wrote as a group; that they would one day play at the foot of the Pyramids and that a lunar eclipse would coincide with one of their shows there; that a large shooting star would streak across the sky as they were about to revive Dark Star at the Greek Theater; that Brent Mydland's last show would fall on the ten-year anniversary of Keith Godchaux's death; that the Dead's last year would "fulfill" two tongue-in-cheek Deadhead prophecies--"Trouble Ahead, Jerry in Red" (he wore a red T-shirt onstage at the start of the last tour) and the belief, spurred by an offhand remark made by Phil Lesh, that if Unbroken Chain were ever played live, it would spell the end of the Dead; and finally that Days Between, a haunting meditation on the past and on unfulfilled dreams, would be the last song Hunter and Garcia would write together.

These are only the sensational elements of the story. When one considers the eclecticism of the band members' interests, backgrounds--Phil's devotion to avant-garde classical music, Mickey's percussion-based ethnomusicology, Jerry's vast knowledge of traditional music--and accomplishments, one begins to get to the root of why the gestalt of the Dead's music, history, and personality hold such fascination for us Deadheads. Throw in the fact that the Dead are, personally, a bunch of genuinely funny guys and the given at the root of all this--that the music is fantastic--and you've got yourself a fascinating and lively subject for conversation. So let's talk about the Grateful Dead.

This little book about the Dead first took seed in the many pleasant hours I've spent over the years "talking shop" with friends. Conversation about the Dead's music inevitably tangles with talk of their history, both as written in fanzines and books endlessly pored over and, more importantly, in the oral realm of rumors and ephemera. And of course there are the tapes, those endlessly circulating pieces of plastic that bear performances both sensational and horrible (though always interesting), amusing bits of stage chatter, "overheard" technical talk among the band and its crew, and now, sadly, the sum of the Grateful Dead's music. When I get a tape of a "new" show, the first thing I want to do is listen to it, the second, share it. This is the currency of interest in the Dead--the sharing of the music and the stories, opinions, and ideas that go with it.

Dead to the Core is meant to be my end of an extended conversation about the Dead with you, the reader. My hope is that reading this book will be an interactive process. I hope that you'll find yourself checking out tapes you haven't listened to in years or become inspired to search out shows of which you weren't aware. Given the subjective nature of much that I've written here, maybe you'll find yourself arguing with the book--hopefully that, too, will send you to your tape collection, to relisten to a performance I've panned and you like, or vice versa. My intent is to engage you in a good old conversation about the Dead. Let's chill and pull out some tapes.

My inspiration for the form of this book is old-fashioned almanacs, books that not only supplied farmers with necessary information on the seasons, planting, and growing but were filled with stories, folk wisdom, recipes, and humor. Here our main discussion is of the Dead and their performances, but sidebars on the interpretation of songs, the observations of fellow Heads, and pieces of trivia and lore can be the asides and tangents that sprout from any good conversation.

There's a certain organic symmetry between the way an actual almanac is laid out, with emphasis on the seasons, and a discussion of the Dead's career. Seasons have always had significance for the Dead and Deadheads within the touring year, and one can find parallels to the seasons in the story of the Dead's career as a whole. It's almost completely natural to take such a view, given the cyclical and seasonal motifs present in so many of the Dead's songs. Hunter and John Barlow have incorporated the birth and nourishing decay of the natural world, as well as evocations of specific seasons, into much of their best work for the Dead, and the tunes that the Dead chose to cover often shared these elemental themes. This book, which focuses on what are arguably the richest years to mine for exceptional performances, is organized according to seasons, with the conceit that the Dead's spring represents their earliest years, and so on.

With so much music out there, I've tried to focus the bulk of my attention on the "monster" years and eras. These are of course also a subjective matter, but I've chosen 1966-67, 1968 (in the form of the Mickey and the Hartbeats shows), 1969, 1970-71, 1972, 1973-74, 1977, 1978, 1979-81, 1985, 1987 (Dylan and the Dead), 1989-90, and 1990-91. Even with so many years covered, there were some agonizing decisions: I dropped 1976 and added 1978; I thought long and hard over whether to include 1982 and 1988 but ultimately decided they weren't as consistently fine as the other years represented. This subjective approach has also left the Dead's last few years out of the closer picture at least, to which you may take issue. My feeling is that the Dead reached a peak in 1990 that carried over into 1991, took a precipitous dip in 1992, experienced a renaissance of sorts in 1993 with new material and some generally mind-blowing performances, and declined gradually but definitely from that point on. To help remedy the "gaps" in my coverage, I've included an appendix of additional show reviews from throughout the Dead's career. Perhaps some champion of the years I've passed over will come forth with a book focusing on those--I'd enjoy the "conversation" and insights such a book would offer. As it is, we have many years of killer shows to go through, so make yourself comfortable and let's talk about the Dead.