Excerpt

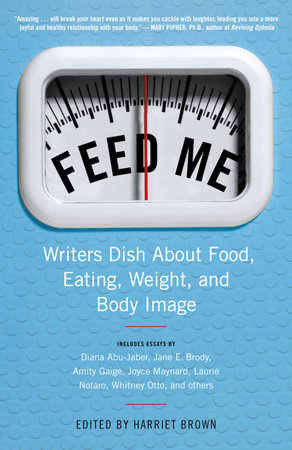

Feed Me!

INTRODUCTION

Harriet Brown

The one piece of jewelry I never take off is a necklace, a gold chain with a single gold charm in the shape of a fork. I wear it the way other people wear a cross or a Star of David—to hold close something as necessary as life itself. I wear it to remind myself to celebrate food and not fear it, to enjoy it and not abuse it.

I wear it to remember (as if I could forget) how my daughter fell down the rabbit hole of anorexia, and how food was the medicine that cured her. Six times a day our family sat down together and ate, bite after agonizing bite. Food nourished her body and brain, mind and heart and soul, back from the terrible borderlands of anorexia.

I wear the necklace in honor of the power of food. We eat the way we breathe—instinctively, without being taught, as a matter of survival. You can live without booze or drugs, but you can't live without food, not for long, any more than you can not breathe, not drink, not sleep.

And maybe that's why the act of eating is so fraught in this culture: because it's not optional. Because we have to do it, three or four times a day, every day. It calls to mind our creaturely origins and holds the potential to affect our physical selves. In an appearance-driven culture, we believe—we seem to want to believe—that food can make us large or small, powerful or weak, attractive or ugly. We are, increasingly, judged by both what we eat and how we look.

And man, are we judged! I doubt there's been another time in American history when what you put in your mouth has come with such a heaping side of shoulds and don'ts. It's the rare woman today who doesn't know the dark side of the fork, the way food can be a curse rather than a cure, a source of anxiety rather than sustenance. No wonder so many of us have “issues” around food and eating. I've seen grown women cringe at the sight of a plate of pasta. I know women who swear they'd be happy if they just Never. Had. To. Eat. Again. I've felt that way myself. As much as I love food (and I do), I have on occasion wished I could just give it up forever.

The essays in this collection explore many aspects of the relationship between food and looks, eating and body image, appetite and desire. They are poignant, thought-provoking, wise, and hilarious. And they reflect not only the experiences of this talented group of writers—they reflect the experiences of so many of us in the twenty-first century. Whether they're describing the indignities of shopping for clothes in a size zero world, the paradigm shift of another culture's perspective on weight, or the dawning understanding of a mother's experience with food and love, these writers speak to all of us who have ever worried about how we look or what to eat.

The pressure to be thin is now felt by both women and men. It starts earlier than ever, a fact that may explain why children as young as six are now suffering from eating disorders. Wendy McClure's poignant essay, “Day One,” describes the first day of the first diet of her life, at age ten. Alas, it was only the first of many diets McClure embarked on out of her longing to fit into the cultural mainstream—a longing most of us can relate to all too well, whether we're just ordinary folks or elite models like Magalei Amadei. Amadei's essay, “Top Model,” describes her ironic struggle with body hatred and bulimia even as her face was gracing the covers of Vogue, Elle, Glamour, and other fashion magazines.

The conflation of eating and appearance affects every corner of our lives, as Joan Fischer points out in her mordantly funny essay, “Take This Cake and Shove It.” Fischer's only slightly tongue-in-cheek piece offers a Swiftian solution to the interior conflicts of food and appearance, food and sex, food and love.

The average American woman eats about eighty thousand meals as an adult, and each and every one of them involves choices about fat and sugar, carbs and calories, organic and processed, how much and what. Every choice can and often does trigger a tidal wave of feelings, from self-loathing to celebration. In modern-day America, feeding yourself is an act of bravery.

It doesn't start out that way. We're born knowing hunger and satisfaction. Babies practice sucking in the womb. But if you've ever tried to get a baby to eat when she's not hungry, you know how powerful the internal self-regulation mechanism can be. Women especially are taught early on to ignore our appetites and to deny ourselves what we're longing for. There are consequences to such self-denial, as Dana Kinstler notes in her bittersweet essay, “Sugar Plum Fairy,” a chilling description of anorexia from the inside out.

In fact, I think that's the true definition of disordered eating: eating that's divorced from real hunger. Our real hunger, not what our parents or our doctors or the media tell us we should be hungry for.1* By the time we're adults, many of us have only the faintest sense of our own appetite. We don't know when we're hungry and when we're full. No wonder we obsess over the numbers on the scale, the curve of our hips, the fat content of our yogurt. No wonder we struggle with so many food-related fears: The fear of not getting enough. The fear of not being able to stop. The fear of taking up too much room.

No wonder, really, that we've become so afraid of food. I've been reading studies and books and following news stories and blogs about fat for the last two years. In that time we've been warned that fat can cause diabetes, heart disease, cancer, and even global warming. Fat is contagious—if you've got a fat friend, even if she lives hundreds of miles away, you are (supposedly) more likely to get fat yourself. Fat has become a moral issue, and what and how you eat is now a religion. A piece of chocolate cake isn't just flour, butter, cocoa, sugar, eggs, baking powder, and milk; it's now a dangerous object, something that can kill you and then send you straight to hell.

On the other hand, a Baggie full of celery sticks might as well come with a halo. It's one more way to abnegate the self, something we women are trained from an early age to aspire to do. Like the joke about the miser who feeds his horse less and less each day until finally the horse dies of starvation, and the miser complains to his friend, “Why did he have to go and die just when I had him trained to live on nothing?”

Why indeed?

And so I wear the necklace to remind myself (to paraphrase the song) that a fork is just a fork, whether it holds lettuce and tomato or fettuccini Alfredo. A fork is a means to an end, and on good days, that's how I think of food, too. It's a way to care for myself, and for those I love, through the steady, courageous, often fraught act of eating, one spoonful at a time.