Excerpt

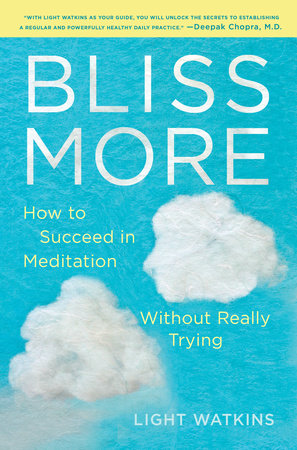

Bliss More

INTRODUCTION

It’s Time

It’s very hard.

I don’t have time.

I’m not in the mood.

I don’t really need it.

I do it only when I need to, but on my own terms.

I can’t sit still for very long.

I like the idea of it more than the act of it.

My meditation is drawing.

My mind is too busy

These are all common excuses I’ve used in the past for not enjoying a regular, daily, seated meditation practice. Do any of them sound familiar?

My involvement in meditation dates back nearly twenty years, but I will tell you up front that the overwhelming majority of my initial efforts were, at best, mediocre and, at worst, an exercise in futility—and by

initial I’m referring to the first few

years of dabbling.

I first got the idea to try meditating while in yoga classes, where my teachers mentioned that the sole purpose of doing yoga was to prepare our bodies for seated meditation. The various spiritual books I was reading at the time also echoed the importance of meditation as a path to experiencing inner bliss, or nirvana, an internal experience reportedly so serene that you would lose awareness of all of your worries, doubts, and fears and be bathed in a feeling of oneness. Who could resist such a promise? I didn’t need any more convincing that meditation would do me a world of good, but I was skeptical about my ability to get my mind to the needed place.

I lived in New York at the time and found a weekly class (the cost was a five-dollar donation) held in the bell tower of the historic Riverside Church, close to my apartment. Martha, the facilitator, started off by telling us about her meditation master, a professional snowboarder and music producer who gained enlightenment on a snowy mountaintop in Nepal after a miraculous run-in with a Buddhist monk. He taught meditation and spirituality for many years and died in his forties (Martha was vague about his cause of death, which I discovered later was suicide), leaving behind an archive of New Age music he produced, to which his students began meditating.

Martha instructed us to sit up tall (with our backs erect, not touching the chair), close our eyes, and give our full attention to one of the songs that was composed by the aforementioned meditation master. While listening, she encouraged us to feel the sensations in our body and mind, and be present to the sounds and vibrations within the song. If our mind got distracted and began veering off to some errant thought, we were to let go of the thought and return our attention to the New Age music, which sounded like a mash-up of smooth jazz and opera. This was not what I was expecting. But I sat there trying to remain open to the possibility of having the intended meditative experience. Maybe the monk would appear to me in my meditation, I thought—half sarcastically and half optimistically

Four minutes in, I felt nothing but frustration. When the song ended, Martha had us open our eyes and share our experiences. One woman reported hearing the subtle sounds embedded within the song. The guy next to me said he felt a delightful tingly sensation in his hands and feet. Others reported similar experiences of movement of energy, or celestial epiphanies. I kept quiet, because the entire time I felt like I had been just sitting there, listening to New Age music with my eyes closed.

We “meditated” through three or four more songs that first night, and although I desperately wanted to intuit some hidden message about the universe—or simply just feel anything— nothing special happened. Maybe I was trying too hard, I thought. Or perhaps I needed to come back and give it another try next week. Maybe it would take another three months . . .

Disappointed, I dropped my five-dollar bill into the donation bucket on the way out and rode my bike home, not fully sure if I would ever crack the elusive meditation code. Being as curious as I was skeptical, though, I vowed to return to Martha’s group, even if it meant remaining insecure about my inability to silence my mind and feel the supposed bliss of meditation.

I took personal responsibility for my lack of success. Could it have been all the fast food and soda pop I consumed while growing up in Alabama? Was it possible I had a genetic mental block that prohibited me from achieving the elusive state of bliss? Could it be that I was already enlightened and didn’t need to meditate at all?

Nah. Turns out I just went to the wrong class.

Unfortunately, it would take another couple of years of dabbling in different meditation scenes before I figured that out. In the meantime, the novelty of telling people that I meditated was enough to keep me curious about the practice. They didn’t have to know that I wasn’t actually experiencing anything in meditation other than my normal thinking mind. In fact, nobody had to know.

HOW NOT TO MEDITATE

I heard several of my yoga teachers insist that there is no “right” way to meditate—that we are our own guru, and therefore we should do what feels right to us in the moment. Therefore, I constantly wondered if I was practicing the best style for me.

At various times in those early years, I tried meditating with my back straight and legs crossed, as I had seen monks do in movies. I tried meditating while lying down, meditating in a field of grass, meditating at the end of yoga class, meditating while sitting on a yoga bolster, meditating on my friend’s living room floor. I tried astral-traveling meditations, channeling meditations, communing-with-my-spirit-guide meditations, Zen meditations, mindfulness meditations, barefoot-walking meditations, holotropic-breathing meditations, mala-bead meditations, and staring-at-the-candle meditations, as well as frequent meditation sits at the local Hare Krishna temple.

Gradually, it dawned on me that if meditation delivers a blissful experience, it must happen about as often as Halley’s Comet appears in the night sky. By far the more common experience I had was physical pain from sitting with my back straight, interspersed with the frustration of battling my mind, chased with heavy doses of boredom.

Over time, my default position became sitting with my legs crossed, with my back as straight as possible, while resting my palms on my thighs, and with my thumb and index fingers lightly touching. But time and again, instead of feeling my chakras align, or my energy shift—or

anything, for that matter—mostly what I felt was searing pain in my lower back while my bare ankles dug into the hard floor so that I could keep pressing my back into a more upright position. Meanwhile, my erratic mind played variations of good-cop-bad-cop, bad-cop-bad-cop, and bad-copworse-cop when it came to my ability to meditate with success, which often left me checking my watch every thirty seconds and counting down the minutes until the dreaded experience was over.

I was becoming increasingly discouraged and jaded. Why were people so enthusiastic about this spiritual torture experience? How could something so obviously laborious continue to exist for thousands of years? How did the word “bliss” ever come to be associated with such a thoroughly unblissful experience? I felt like I was living in some sort of bizarre meditation version of

The Emperor’s New Clothes—standing on the sidelines as the procession went by, witnessing everyone else sing the praises of this glorious practice that was supposedly garbed in pure bliss.

Ironically, when I became a yoga teacher a few years after my inaugural meditation experience in New York, I began leading guided meditations at the end of my classes. I was seen as a meditation expert even though I never received meditation instruction during my yoga teacher training, nor did I have a consistent meditation practice of my own at the time. In order to compensate for my personal inability to sit in silence, I did what many yoga teachers do, and parroted the stock meditation instructions I heard

my yoga teachers give over the years: let go of your worries, visualize waterfalls and white lights enveloping you, calm your mind, and don’t forget to notice your breath in the process. In other words, I became the emperor!

Nobody needed to know how much of a monkey mind I was experiencing while I was guiding them, or how much I struggled to feel my own bliss. I knew how to look and sound the part, soft voice and all. Maybe that’s the jig, I thought: everyone is pretending, and meditation is all about faking like you’re blissed out even though you aren’t.

What I didn’t know then, and probably wouldn’t have believed if someone had told me, was that I was about to experience a 180-degree turn in my attitude toward meditation. Indeed, meditation would soon become the bliss-inducing practice I had always hoped it could be, and would revolutionize my life in the most unexpected ways.