Excerpt

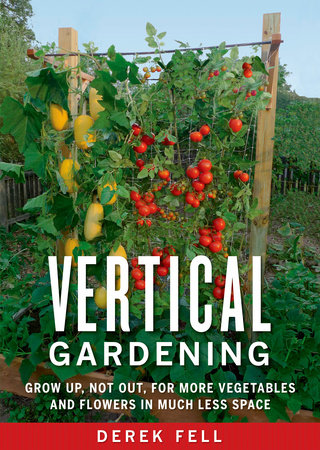

Vertical Gardening

What Is a Vertical Garden?

CHAPTER 1

I'd like to welcome you to a garden where vegetables, flowers, and fruit all grow, climb, and twine upward to create a beautiful landscape that saves space, requires less effort, produces high yields, and reduces pest and disease problems. Whether your goal is armloads of flowers, a bountiful vegetable garden, or a productive fruit harvest, I'll show you how narrow strips of soil, bare walls, and simple trellises and arches can be transformed into grow-up or grow-down gardens with just a few inexpensive supplies or purchased planters. I've been testing gardening methods in my own 20-acre garden at Cedaridge Farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, for 20 years, and I want you to discover the same delights and benefits of vertical gardening that I'm enjoying.

Vertical gardening is an innovative, effortless, and highly productive growing system that uses bottom-up and top-down supports for a wide variety of plants in both small and large garden spaces. There are hundreds of varieties of vegetables, fruits, and flowers that are perfect for growing up freestanding and wall-mounted supports and in beds or containers.

Best of all, vertical gardening guarantees a better result from the day your trowel hits your soil--by shrinking the amount of garden space needed and reducing the work needed to prepare new beds. Chores like weeding, watering, fertilizing, and controlling pests and diseases are reduced considerably, while yields are increased, especially with vegetables like beans and tomatoes. A vining pole bean will outyield a bush bean tenfold. Moreover, a vining vegetable is capable of continuous yields--the more you pick, the more the plant forms new flowers and fruit to prolong the harvest. A bush variety, by contrast, will exhaust itself within 2 to 3 weeks.

A Japanese wisteria vine twines upward through the canopy of this small- scale replica of Monet's bridge. The long flower clusters offer an intimate and fragrant resting spot while viewing the water garden at Cedaridge Farm.

With vertical gardening methods, you'll also discover that many ground- level plants pair beautifully with climbing plants, so you can combine different types of plants to create a lush curtain of flowers, foliage, and bounty. With a mix of do-it-yourself and commercially available string supports, trellises, pergolas, raised beds, Skyscraper Garden trellises, and Topsy-Turvy planters, vertical gardening saves a lot of time and work, lessens backbreaking tasks, makes harvesting easier, and is perfect for any size space, from a patio container and a 1 x 4-foot strip of soil to a landscape trellis and the entire side of a building.

LAYING THE GROUNDWORK

I first encountered a successful no-dig garden at the Good Gardeners Association in Hertfordshire, England. I visited the home of the group's founder, the late Dr. W. E. Shewell-Cooper, in 1970, when I went to interview him for an article in Horticulture magazine. On my return to the United States, I also discovered The Ruth Stout No-Work Garden Book, which was one of the first books that advocated a system of no-dig gardening through in situ (in place) composting. Stout explained how she created planting beds by putting down newspapers to suffocate existing weeds and grass; piling on layers of organic waste, such as spoiled hay and kitchen scraps, as mulch to decompose; and then planting directly into this compost. This system of gardening has appealed to many people during the past 40 years, even though its focus has been gardening horizontally.

Many no-dig plots based on Ruth Stout's book have been established in public demonstration gardens, including one maintained by the ECHO Foundation (Educational Concerns for Hunger Organization) near Fort Myers, Florida. The foundation began its first no-dig garden in 1981, which remained in continuous production for years as a vegetable garden in the middle of what had been a lawn. It was never plowed, cultivated, spaded, or hoed. Around the same time, engineer-turned-author Mel Bartholomew introduced his own concept in his book Square Foot Gardening, which promoted raised beds and intensively planted crops that allowed gardeners to grow more in less space. Mel has convinced millions of gardeners around the world to switch to easy no-dig raised beds. And then along came Patricia Lanza with her blockbuster book Lasagna Gardening. After struggling to amend the soil in her gardens, she, too, realized that layering compostable ingredients was the best way to start new garden beds, and she's been growing flowers, vegetables, and herbs for years in her "lasagna" layers.

For the past couple of decades, I've studied, tried, and implemented gardening systems that produce better results in less space with less work. Many no-dig methods were developed specifically for gardening horizontally, but I've found that these same no-dig techniques are even better suited to vertical gardening. With vertical gardening, plants require much less space than plants that grow horizontally, so those same layering techniques are even more efficient when used in conjunction with the small-footprint beds I recommend. While most no-dig systems suggest that a 6-inch depth of fertile soil is adequate, I prefer a soil depth of 6 to 12 inches in a raised planting bed, because vining plants generally have more vigorous root systems than dwarf plants or plants grown horizontally. Plants grown in 6 to 12 inches of fertile soil respond magnificently to that extra soil depth by delivering maximum yields.

THE BENEFITS OF GROWING VERTICALLY

If you've gardened in long, horizontal beds for even a single growing season, you've probably thought to yourself, "There has to be a better way." Well, you're right--there is a better way. Vertical gardening offers many advantages over horizontal growing.

Smaller beds to prepare and maintain. When growing plants with a vertical habit, you'll need a bed only as large as the root systems of those plants-- one that's much smaller than a traditional bed. When you plant horizontally, you tend to have narrow rows of plants and wide swaths of soil between them. It's those wide swaths that drink up much of the water, send up innumerable weeds, and consume the nutrients needed by your plants. With vertical gardening, you prepare only small spots or strips of fertile soil--just enough to give plants a nutritious base from which to climb up supports. These vertical garden beds require less compost, fertilizer, and water, and only a few bucketfuls of mulch or a little black plastic to control weeds. Compost goes further when you cut back on bed space, so you won't need to buy, generate, or use as much compost in order to amend your soil each season. And whether you plan to water with a watering can or use a drip irrigation system, you'll find that watering your small plots of soil is a cinch, and your drip hose can be short.

A simple vertical garden is perfect for a paved or soil surface, 2 feet wide x 4 feet long, with room for four vining plants such as a tomato, cucumber, climbing spinach, and pole bean.

I'm an advocate of no-dig beds, because I've seen the results others have achieved, in addition to my own successes. You can easily create a no-dig bed by spreading homemade or store-bought compost onto bare soil--or onto a layer of newspapers to kill surface weeds or turfgrass--and leveling the new bed with a rake. Spreading compostable layers on top of your newspaper weed barrier will create a fluffy, nutrient-rich planting bed (the method called in situ or sheet composting).

To compost in situ, I make sure my newspaper layer is at least 15 pages thick and that the edges overlap like the scales of a fish. This excludes light from the ground beneath, killing grass and weeds. On top of this, I generally place a 6-inch layer of grass clippings, a 6-inch layer of shredded leaves (I use a lawn mower to shred them), and then a layer of kitchen waste (often including banana peels, eggshells, fish bones, and potato skins). This stack is then topped off by a 1/2-inch layer of wood ashes. Other good composting ingredients include well-rotted animal manure (like cow and horse), sawdust, shredded newspapers, pine needles, and hay. Hold the sides of this in-situ compost bed in place with boards, landscape ties, or even stones or bricks.

Skyscraper structures can be assembled above a raised bed to create a freestanding unit, ready for edible vines such as pole beans and indeterminate tomatoes or flowering vines such as morning glories and climbing nasturtiums.

Do-it-yourself supports and trellises. While vertical gardening depends on a variety of supports and trellises, you'll find that it's easy to make your own. I make many of my own trellises from bamboo canes that I grow myself, or from pencil-straight pussy willow stems. It's simple to take canes or willow stakes and space them 1 foot apart to make posts, and use thinner, more pliable canes threaded through them horizontally to make strong, good-looking trellises. You'll see lots of examples of homemade trellises in the photographs in this book. Of course, ready-made trellises are available from garden centers, large hardware stores, and even big-box discount stores. Sturdy metal ones are suited for heavier vines, like melons and winter squash. In this book, you'll also discover the Skyscraper Garden trellis, a post-and-netting support I designed specifically for growing vegetables and flowers vertically. Skyscraper Garden trellises can be freestanding or wall-mounted and can be grouped in raised beds to create an efficient, highly productive, and attractive gardening space.

At Cedaridge Farm, I've created long raised beds and use Skyscraper Garden trellises to support vining crops above low-growing foundation vegetables and herbs.

Vertical pots and containers for very small spaces. If you don't have any (or much) garden space--say, just a concrete patio or a balcony--or if you can't easily amend your soil or build a raised bed, then consider using tower pots or other containers that help you grow upward in a column. Tower pots are commercial containers that stack one on top of the other and enable you to grow vertically a variety of plants that don't vine (such as lettuce, peppers, and strawberries). Plus, you can easily add trellises and supports within containers or "planted" just behind containers to create a vertical garden in a limited space. And if you need to be really creative with garden space, try mounting containers at various heights on a fence or wall to create a visual vertical garden.

New plant varieties to explore. The choices of climbing plants may surprise you. Among the vegetables, try growing climbing spinach (it's heat resistant and tastes even better than the regular cool season spinach), trellis-loving snap peas with edible pods, and the fabulous climbing 'Trombone' zucchini that produces a vine 10 feet tall and loaded with fruits. All of these grow up, not out. Vining cucumbers, single-serving vining melons, and even sweet potato vines are all suitable for growing upward, instead of sprawling outward across the ground and consuming more space than you can easily care for during the season. And if you've ever grown vegetable spaghetti (also known as spaghetti squash) in a traditional garden, try growing it up a trellis instead: Allowed to grow across the ground, vegetable spaghetti is an aggressive vine that will suffocate anything in its path; but when it's grown up a trellis, it shoots skyward with tendrils that grasp latticework or garden netting, producing up to a dozen fruit on a vine.

On this shady fence, wooden buckets are mounted at various heights with strong metal brackets and feature lush plantings of fuchsia and impatiens for an appealing vertical flower garden.

You may even find that vertically grown vegetables taste better. Bear in mind that all that vine foliage collects more chlorophyll than a bush variety of the same vegetable, and this may help to promote better flavor. It is said that the French Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir had such a refined taste for good food (his wife, Aline, earned a reputation as one of the finest cooks in France) that he could tell the difference between snap beans grown on poles and those grown on dwarf, bushy plants, because to him the vertically grown beans had superior flavor. Based on my own experience, I agree with him! Of course, the king of vegetables--the tomato--benefits from growing vertically, especially those varieties classified as indeterminate (with vines that can reach 20 feet or more) in seed catalogs and on plant labels. When you look at world-record harvests for tomatoes, all of the winning plants were staked to grow vertically, with some growing more than 25 feet high, producing hundreds of fruit from early summer to fall frost.

You can try many new plant varieties in your vertical garden. Using a strong trellis or a bamboo support and heavy-gauge garden netting, experiment with the edible gourd 'Cuccuzi'; long, straight fruits develop when the fruit is allowed to hang.

One of the bigger benefits of vertical gardening is being able to grow many different fruits against a wall or along wires or a split-rail fence. Of course, vining fruits like grapes and hardy kiwifruit are ideal, but so are berry crops with long, flexible canes like blackberries and raspberries. Even fruit trees with strong, sturdy trunks have pliable side branches that can be trained to grow flat for long distances against a wall or fence. This practice, known as espalier, significantly reduces the amount of space needed for a generous harvest of apples, peaches, pears, and other orchard trees--and reducing the growing space footprint is one of the tenets of vertical gardening. Be aware that many fruit trees are sold in standard, semi-dwarf, and dwarf sizes, referring to the mature height of the tree. For espalier in a home garden, the semi-dwarf and dwarf are most suitable, producing full-size fruit regardless of the extent of dwarfing.

Flowering vines also tend to be everblooming and provide armloads of flowers for cutting. Sweet peas, nasturtiums, and morning glories will produce curtains of color planted in a short row to climb up garden netting (either attached to a sunny wall or strung between posts as a freestanding trellis). Grow all three together for an incredible kaleidoscope of color. Then explore the dozens of other choices of upwardly mobile and cascading flowers and vines to create a garden that's filled with interesting "living walls," dividers, and curtains of foliage. See the two chapters on flowering ornamental vines (annual vines as well as the perennial and woody vines).

This small-space, nonstop vertical garden is created by positioning a Skyscraper Garden trellis in a 12-inch-deep raised planter box, with a 6- inch-deep planter box on each side. Look at how productive a vertical garden can be! Four varieties of climbing vegetables (such as cucumbers, pole snap beans, tomatoes, and vegetable spaghetti) are growing on both sides of the garden netting in the deep bed, and non-vining foundation plants (such as bell peppers, herbs, and lettuces) are thriving in the shallower beds.