Excerpt

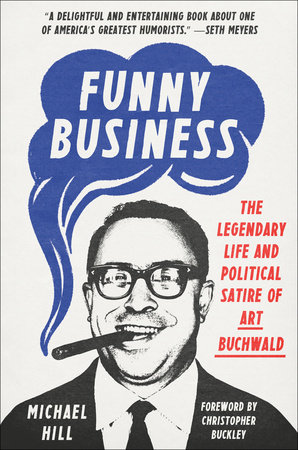

Funny Business

Chapter 1

“Plastered in Paris”Early Years and the Comic Charms of Paris (1948–52)

It is a strange force that compels a writer to be a humorist.

—Dorothy Parker

In the spring of 1948, high school dropout Art Buchwald was having the time of his life. After being discharged from the U.S. Marine Corps at the end of World War II, he had enrolled at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles as a “special student” under the GI Bill. “I’m having a ball,” the new college man wrote his sisters, Alice, Doris, and Edith, back home in New York. “All your predictions about what would happen to me if I goofed off in high school have not proven true. USC sees something in me that you girls never did—a promising brain surgeon, a future member of the Supreme Court or, at the very least, a Nobel Laureate in literature.” Art took great pleasure in writing to his father and sisters about his “charmed life” in California. “I have never been happier in my life. . . . I wear a cotton sweater that could be taken for cashmere, and nobody gives me a bad time or tells me what to do,” he wrote home with glee. “As soon as I mail this letter I am going out to buy saddle shoes and get a date with a Trojan coed—Jewish, of course.”

Art lived with thirteen other students in an off-campus boardinghouse run by an odd woman named Mrs. Liebschen, who, according to Buchwald, seemed to possess a deep-seated hatred for anyone not of the Aryan race. Although she never displayed any open hostility toward Buchwald as a Jew, he always found her fondness for a “German newspaper with a swastika on the front page” a bit unsettling.

As a “special” non-degree student, he was the “envy” of his classmates since he could enroll in any course that caught his fancy. “When asked what I intend to do with my life,” he told one of his sisters, “I reply, ‘I’ll probably be a writer for the cinema, or start a book on the corrupt athletic programs in our university system.’ ” In an effort to hone his skills as a writer, Buchwald took courses in drama and creative writing. “Foreign languages and the sciences interested me as much as nuclear waste,” he later said. In one of his writing classes he wrote a theme paper titled “A Short Report on Satire,” an ironic bit of foreshadowing in which he claimed that humor and satire can act as a “civilizing agent” on society, tempering its political and cultural excesses. “The satirist is always at war with society,” he wrote, “but I think it’s a worthwhile fight.”

When not in the classroom, Buchwald enjoyed the time he spent as managing editor of the campus humor magazine, Wampus, and as a columnist for the Daily Trojan newspaper, both of which provided an early outlet for his brand of humor and satire. “USC was my training ground before I went out into the world and stuck pins into the rich and powerful,” he later wrote.

He even tried his hand at a comic theatrical production, once writing a musical play based on the “atomic experiments at Bikini Island,” called No Love Atoll. Despite its catchy title, the play closed after a campus run of only four days.

Then, during his third year at USC, Buchwald struck gold. One morning over coffee he learned from a fellow student about a tuition benefit program under the GI Bill that would permit him to study in Paris—the “Mecca of writers” and the city of romance—where, he told friends, the “streets are lined with beds.” His “dream was to follow in the steps of Hemingway, Elliot Paul, and Gertrude Stein,” he declared. “I wanted to stuff myself with baguettes and snails, fill my pillow with rejection slips, and find a French girl named Mimi who believed that I was the greatest writer in the world.”

After bidding goodbye to his friends and the peculiar Frau Liebschen, Buchwald hitchhiked from Los Angeles to New York, where he booked a one-way ticket to France on a former troop carrier. As the ship hit the open seas, Art had no doubts that he had made the right decision, and he was as happy as ever.

During the long ocean voyage to France, Buchwald spent evenings out on the deck reflecting on his past. “I started adding up everything that had happened to me since my birth,” he later wrote. “My life had been a series of zigs and zags. Soon after I was born, my mother was confined to a mental institution, where she remained for thirty-five years. With my three sisters, I was placed in the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in New York, and then boarded out with foster parents . . . in eight different kinds of homes with God knows how many strangers.”

Because his father, Joseph, a struggling curtain salesman in New York, was unable to afford the expense of his wife’s hospital bills and the cost of supporting a family, he had been forced to give up the care of Art and his three sisters to foster homes in and around New York City. Although his father came to visit as often as he could, Art felt abandoned. “I didn’t belong to anybody,” he later said of his childhood.

While the majority of Art’s school years were spent at PS 35 in Hollis, a middle-class neighborhood in Queens, his real education came from experiencing life on the streets, where he quickly developed a reputation for being a “bold and street wise” young man. Art traveled all alone on the subway into the city, where he wandered into coffee shops and hotel lobbies, fascinated by the colorful cast of characters he saw everywhere. “Later when I became a fan of Damon Runyon’s, I knew better than most people what he was talking about,” Buchwald would later recall.

But perhaps the most important lesson he learned during those sad early years was that the way to cope with the hard knocks of life was to be funny and to battle adversity with a smile. “I was the class clown. . . . I managed to get people to laugh. That was my way of getting acceptance. I learned very quickly that if you are a clown, people will be nicer to you.” Increasingly frustrated by the loneliness and anger he felt, one day he vowed to himself, “This stinks! I’m going to become a humorist.”

In 1942, a year after America entered World War II, seventeen-year-old Buchwald dropped out of high school and enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps with forged permission papers. After basic training at Parris Island, South Carolina, he shipped out to a Marine airfield at Cherry Point, North Carolina, where he was inexplicably assigned to the base ordnance school, handling bombs and other lethal inventory—an unlikely post for someone who lacked any manner of mechanical or technical aptitude. During his off-duty hours, far from the airfield’s stock of high-grade explosives, Buchwald started smoking cigars, a habit that quickly became a soothing obsession. “Cigars [were] a very important part of my life. They were my pacifier, my security blanket, even my Valium. Whenever I was feeling good, I put one between my lips, and whenever I was feeling bad, I lit one up.”

After Cherry Point, his unit, VMF 113, was ordered to the Marshall Islands in the Pacific, where he saw action at Eniwetok and Engebi in 1944. In addition to his ordnance duties, Buchwald was editor of the unit’s humorous newsletter, The U-Man Comedy. In one issue, after his unit scored several impressive aerial successes against the Japanese, Buchwald published a front-page open letter to Tojo, the Japanese prime minister and head of the Imperial army, proclaiming that it was time for him to “throw in the towel.”

In November 1945, three months after the end of the war, Buchwald was discharged from the Marine Corps and returned to New York. Soon feeling restless and seeking a new adventure, he abandoned New York and headed to the West Coast, setting his sights on becoming a comic screenwriter in Hollywood and, during his off-hours, making “love to Ginger Rogers.” When both dreams were quickly dashed he applied for admission and matriculated at USC. But after three carefree years of college life he was ready to move on.

Now, here he was on his way to Paris, “every young writer’s dream,” he declared to himself one night as the “ship sailed smoothly through the water” to the port of Le Havre. He “felt an unbelievable surge of happiness” about the great adventure that lay ahead. But not even in his “wildest dreams” could he have foreseen “how wonderful the future would turn out to be.”

Shortly after his arrival in Paris in late June 1948, Buchwald wrote a letter home to a former high school classmate:

I am in Paris and I got a great buy on a French beret. The sidewalk salesman told me that it had belonged to his grandfather, who posed for Van Gogh’s most famous self-portrait.

My money is still holding out. The secret is French bread and cheese. It is a banquet and all I need to keep me going. I haven’t fallen in love yet, as I’ve decided to play hard to get. If a French baroness drives by and asks me to jump into her car, I will tell her, “I prefer to walk.” And then add, “Just because I am an American student, I have no intention of going to Maxim’s and drinking a bottle of champagne with you and letting you take advantage of me in the back of your limousine.”