Excerpt

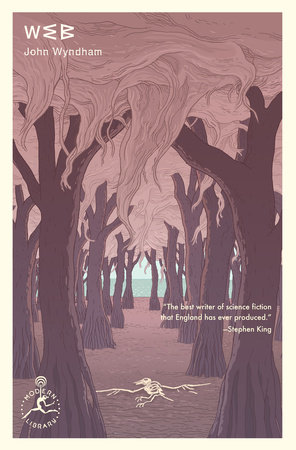

Web

OneThe question I find most difficult to answer; the one which always crops up sooner or later when the subject is mentioned, is, approximately:

“But how on earth did

you come to get yourself mixed up in a crazy affair like this, anyway?”

I don’t resent it—partly, I suppose, because it does carry the implication that I can normally be regarded as a reasonably sane citizen—but I do find it scarcely possible to give a reasonably sane answer.

The nearest I can come to an explanation is that I must have been a little off-balance at the time. This could, I imagine, have been the effect of delayed shock unnoticeable as an aberration, unsuspected by myself yet a shock deep-seated enough to upset my critical sense, to blunt my perceptions and judgment.

I

think that may have been the cause.

Almost a year before I met Tirrie and so became “mixed up in the affair” I had a nasty accident.

We were driving—at least, my daughter Mary was actually driving, I was beside her and my wife in the back—along the A272, not far from Etchingham. We were doing, I suppose, about thirty-five when a lorry that must have been traveling at over fifty overtook us. I had a glimpse of it skidding as its back wheels were level with us, another of its enormous load tilting over us . . .

I came round hazily in bed, a week later. They let two more weeks go by before they told me that my wife and Mary were both dead.

I was in that hospital for two months. I came out of it healed as it seemed to me—but dazed and rudderless, with a feeling of unreality, and an entire lack of purpose. I resigned my post. That, I realize now, was the very thing I ought not to have done—the work would have helped to get me back on balance more than anything else, but at the time it seemed futile, and to require more effort than I could make. So I gave up, convalesced at my sister’s home near Tonbridge, and continued to drift along there in a purposeless way, with little to occupy my mind.

I am not used to lack of purpose. I suspect that it creates a vacuum which sooner or later has to be filled—and filled with whatever is available when the negative pressure reaches a crucial point.

That is the only way I can account for the undiscriminating enthusiasm which submerged my commonsense, the surge of uncritical idealism which discounted practical difficulties and seemed to reveal to me, finally and undeniably, my life work and my justification, when I first heard of Lord Foxfield’s project.

Alas for disillusion. I would like to convey if I could the whole bright prospect as I saw it then. It was such stuff as dreams are made of. But now it is gone, sicklied o’er with the pale cast of cynicism. I look at myself as at someone else moving half-awake . . . and yet . . . and yet at times I feel that there was the spark of an idea, an ideal behind it there was the spark of an idea, an ideal behind it that could have started a flame—had the Fates shown us one touch of benevolence.

The original idea, or the core of the idea, that grew into the Foxfield Project seems to have occurred spontaneously and simultaneously in the minds of his Lordship and Walter Tirrie. The former publicly claims its authorship; the latter was known to claim privately that it was inspired by him. It seems possible that it was a spark thrown off in the course of conversation between them which ignited in both, and was industriously fanned by both minds.

Walter was, by profession, an architect, but perhaps more widely known as an ardent correspondent and persistent setter-right of the world in the columns of several weekly reviews. From this he had graduated to being a moderately familiar figure speaking on platforms devoted to numerous causes. There may even have been some truth in his claim to have introduced the idea to Lord Foxfield, for if one takes the trouble to track back over his letters in the correspondence columns over a few years it is possible to find not only faint inklings of the plan, but also of his feeling that he was the man,

Dei gratia, to realize it. Though it would seem that it was only after his meeting with his Lordship that the insubstantial fragments of the idea began to fall into form.

This possibly took place because his Lordship could contribute more than mere form; he could give it expression, endow it with money, put his weight behind it, and pull strings where necessary.

And why was he willing to back it in all these ways?

Well, one can dismiss straight away all the subtle schemes and dubious intentions with which gossip credited him. His motive was quite uncomplicated and ingenuous: he was, quite simply, a man in search of a memorial.

It is a desire that is not even unusual among rich, elderly men. Indeed, to quite a number of them there appears to come a revelatory day when they look at all those comma-spaced triplets of figures, and are suddenly pierced by awareness of their inability to take it with them, whereupon they are seized by the desire to convert those hollow naughts into a tangible, and usually autographed, token of their successes.

This mood has come upon them through the ages, but of late it has become less easy to fulfill—or perhaps one should say to fulfill it with the desirable distinction of benefaction—than it was even in the days of the old tycoons. The State, now so pervasive, tends to abrogate to itself even the function of benefactor. Education is no longer an outlet; it is free, at all levels, for all. The erstwhile poor—now the lower-income brackets—are housed at municipal expense. Playing-fields are provided by the ratepayers. Public, even peripatetic, libraries are subsidized by county councils. The working-man—now the worker—prefers overtime and the telly to Clubs and Institutes.

A man may, it is true, still found a College or two in some University, but this does not entirely suit every donor’s benefactory urge—for one thing, if there is felt to be a need for such a College someone will finance one anyway; for another, in these days of Government interference no intention or stipulation would be safe. Ministerial decision could easily modify one’s intended seat of higher learning into just another springboard of knowhow, overnight. In fact the field for worthy acts of eleemosynary commemoration has been so sadly reduced that Lord Foxfield spent some two years after the urge struck him in a vain search for a goodwill project which, if he did not undertake it himself, was unlikely to be adopted by any Ministry, Council, Corporation, Institution or Society.

It was a period of great strain for his secretary.