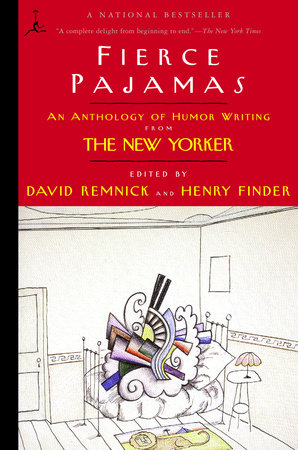

Excerpt

Fierce Pajamas

SPOOFS

WOLCOTT GIBBS

DEATH IN THE RUMBLE SEAT WITH THE USUAL APOLOGIES TO ERNEST HEMINGWAY,

WHO MUST BE PRETTY SICK OF THIS SORT OF THING

Most people don’t like the pedestrian part, and it is best not to look at that if you can help it. But if you can’t help seeing them, long-legged and their faces white, and then the shock and the car lifting up a little on one side, then it is best to think of it as something very unimportant but beautiful and necessary artistically. It is unimportant because the people who are pedestrians are not very important, and if they were not being cogido by automobiles it would just be something else. And it is beautiful and necessary because, without the possibility of somebody getting cogido, driving a car would be just like anything else. It would be like reading “Thanatopsis,” which is neither beautiful nor necessary, but hogwash. If you drive a car, and don’t like the pedestrian part, then you are one of two kinds of people. Either you haven’t very much vitality and you ought to do something about it, or else you are yellow and there is nothing to be done about it at all.

If you don’t know anything about driving cars you are apt to think a driver is good just because he goes fast. This may be very exciting at first, but afterwards there is a bad taste in the mouth and the feeling of dishonesty. Ann Bender, the American, drove as fast on the Merrick Road as anybody I have ever seen, but when cars came the other way she always worked out of their terrain and over in the ditch so that you never had the hard, clean feeling of danger, but only bumping up and down in the ditch, and sometimes hitting your head on the top of the car. Good drivers go fast too, but it is always down the middle of the road, so that cars coming the other way are dominated, and have to go in the ditch themselves. There are a great many ways of getting the effect of danger, such as staying in the middle of the road till the last minute and then swerving out of the pure line, but they are all tricks, and afterwards you know they were tricks, and there is nothing left but disgust.

The cook: I am a little tired of cars, sir. Do you know any stories?

I know a great many stories, but I’m not sure that they’re suitable.

The cook: The hell with that.

Then I will tell you the story about God and Adam and naming the animals. You see, God was very tired after he got through making the world. He felt good about it, but he was tired so he asked Adam if he’d mind thinking up names for the animals.

“What animals?” Adam said.

“Those,” God said.

“Do they have to have names?” Adam said.

“You’ve got a name, haven’t you?” God said.

I could see–

The cook: How do you get into this?

Some people always write in the first person, and if you do it’s very hard to write any other way, even when it doesn’t altogether fit into the context. If you want to hear this story, don’t keep interrupting.

The cook: O.K.

I could see that Adam thought God was crazy, but he didn’t say anything. He went over to where the animals were, and after a while he came back with the list of names.

“Here you are,” he said.

God read the list, and nodded.

“They’re pretty good,” he said. “They’re all pretty good except that last one.”

“That’s a good name,” Adam said. “What’s the matter with it?”

“What do you want to call it an elephant for?,” God said.

Adam looked at God.

“It looks like an elephant to me,” he said.

The cook: Well?

That’s all.

The cook: It is a very strange story, sir.

It is a strange world, and if a man and a woman love each other, that is strange too, and what is more, it always turns out badly.

In the golden age of car-driving, which was about 1910, the sense of impending disaster, which is a very lovely thing and almost nonexistent, was kept alive in a number of ways. For one thing, there was always real glass in the windshield so that if a driver hit anything, he was very definitely and beautifully cogido. The tires weren’t much good either, and often they’d blow out before you’d gone ten miles. Really, the whole car was built that way. It was made not only so that it would precipitate accidents but so that when the accidents came it was honestly vulnerable, and it would fall apart, killing all the people with a passion that was very fine to watch. Then they began building the cars so that they would go much faster, but the glass and the tires were all made so that if anything happened it wasn’t real danger, but only the false sense of it. You could do all kinds of things with the new cars, but it was no good because it was all planned in advance. Mickey Finn, the German, always worked very far into the other car’s terrain so that the two cars always seemed to be one. Driving that way he often got the faender, or the clicking when two cars touch each other in passing, but because you knew that nothing was really at stake it was just an empty classicism, without any value because the insecurity was all gone and there was nothing left but a kind of mechanical agility. It is the same way when any art gets into its decadence. It is the same way about s-x–

The cook: I like it very much better when you talk about s-x, sir, and I wish you would do it more often.

I have talked a lot about s-x before, and now I thought I would talk about something else.

The cook: I think that is very unfortunate, sir, because you are at your best with s-x, but when you talk about automobiles you are just a nuisance.