Excerpt

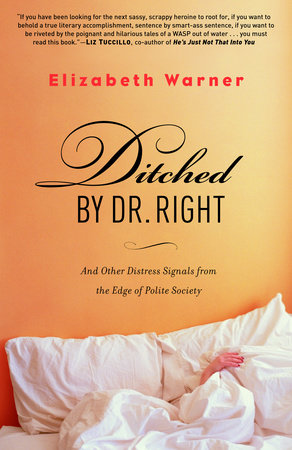

Ditched by Dr. Right

Carbon Dating

This is a true story.

When you grow up in the Protestant blood clot that is suburban Philadelphia, there’s very much a plan at work. One is typically weaned, whelped, and privately schooled, whereupon you move on to the roost-and-spawn phase, with the occasional rinse & repeat. And that’s that. The plan is proven, it’s time-honored, it’s genetically appropriate. Curiously, however, it neither applied to nor worked for me.

In my case, the best-laid plans of mice and men are best left to mice and men.

As the youngest of seven (the next child being seven years older), I grew up in a family that remains astonished I can button a garment and walk upright at the same time. Nor will this change. Were I to develop a fun, easy, at-home way to split the atom, or stem the tide of Parkinson’s disease, they’d still say, Oh, the little one? She doesn’t do too much. But she has nice hair.

They’re pretty sure I put the I in inertia.

My mother, a pathologically elegant woman whom we’ll call the Widow Warner, has maybe four big concerns. The Four Horsemen of her Anglican Apocalypse are

1.post-Soviet Communist domination;

2.my marital status;

3.osteoporosis; and

4.the network cancellation of JAG.

On the day I announced that I was considering a departure from Manhattan, in order to try a Year Abroad in Los Angeles, nobody really knew what to do. Although everyone certainly had something to say. (The Year Abroad actually turned into several, but that’s another story.)

Plus, my proposed relocation seemed even more implausible given that until recently I had regarded Southern California as a kind of backyard to the Antichrist. It was New York’s slower, spoiled, thicker, and more slothful sibling (and I’d never even seen Canada).

Mother was shocked. Then worried. Then horrified. And finally, what-on-earth-am-I-going-to-tell-people bewildered. For one thing, she has always viewed California as a kind of lost, vestigial Spanish colony. And two, she’s long felt that human interaction, fiscal negotiating, and air travel are not the kinds of things her youngest should try to tackle unsupervised. I reminded my family that they had all seen my initial move to New York—where one’s entire net worth would no doubt be forcibly removed either at gunpoint or at Barney’s—as yet another testament to my immaturity. Apparently nobody could recall ever saying anything of the sort. I was sure this and other observations had naturally been relegated to that emotional cedar closet that every youngest child has, which is always chockablock full of accusations, observations, pronouncements, and edicts elder siblings will eternally deny ever having made.

Additionally, we all well remembered that our own great-aunt (a noted ambassador, playwright, and significant backer of causes that seemed uncomfortably Aryan to me) had always said, “California? You can’t get a Goddamned thing fixed in Southern California when you want to. And when do they always tell you it’ll be ready? Mañana. Mañana. Everything’s mañana.” My siblings and I had ignored what may have been her senility, her cultural imperialism, or her genuine racism.

Of course, the Year Abroad idea would simmer codependently for a long while. In the time it might take to (a) groom and promote a boy band, (b) triple the U.S. national debt, or (c) run out the lease on a Jetta, I would acquire some small degree of penny-wisdom. I would fall hopelessly in love with a bright, grumpy, whinging journalist. With whom I was smitten, and who was funny, like you read about. We would be charitably referred to as the Jew and the Shrew. I would spend my twenties stumbling haplessly through the greatest city on earth. I would become wildly proficient at a job that was as heady and rewarding as it was toxic. I would disappoint and embarrass most of my family. All this before I could summon the capacity to awkwardly stare doubt, familial roadblocks, and nonrefundable airfares in the face. And even begin to consider boarding the last Leap of Faith train to the coast.

Nor would any of this have transpired had it not been for the swiftly agonizing departure of one Dr. Right. Here’s what happened.

Everything began one Ides-riddled March. When I had the world by the tail. Or at least by a hind leg. I was a Senior Promotional Copywriter at Time Inc.’s Consumer Marketing Group. This is the in-house advertising agency responsible for the promotion of some twelve magazines to the general public. I authored persuasive marketing copy to readers and consumers. The goal was to bring in new magazine subscribers and keep them on board for the rest of their lives. I was most definitely part of the plan. And thus far, it was working. I was going to live snappily ever after. I had a superb office with several windows and an enormous hexagonal coffee table, largely because I could. I authored million-dollar sweepstakes. My job was to lure unsuspecting Middle Americans into purchasing magazines they didn’t want, wouldn’t like, and probably couldn’t read, all with the promise that they’d love the sneaker phone we’d also send them the instant we got their check or money order. With really tangible results. If we did our job well enough, which I almost accidentally did, we could whip Middle Americans into such a buying frenzy that they’d eat their young if they thought there was an AM/FM clock radio in the deal.

I was genuinely enjoying a kind of secular rot in New York City. But in a good way. The kind of spiritual decay that’s actually quite comforting, particularly when it’s complained about in smart, buzzy bistros brought to you by the colors taupe and veldt. I had a one-bedroom apartment slightly larger than a votive candle in an antiseptic but deceptively cheery part of midtown Manhattan. And most essentially, I was enrolled in a rigorous program of healthy, expensive psychotherapy.

It was a lovely, mindless time of income and ascent. I couldn’t help but bask in the burl walnut finish of familial approval. My family—especially my mother—was delighted. The little one’s on her way. She’s a three-bedroom co-op away from the rest of her life. The best part? I was living with, sleeping with, scheduled to build a future with (and quite satisfied by) a good-natured anesthesiologist heretofore known as Dr. Right. Who really was my soul mate, my future, and the love of my lifestyle. Together we frequented parties where the women all wore black suits and that shell-shaped jewelry that’s supposed to look modest but was purchased with proceeds from IPOs of little start-ups like GM and Exxon. And the impossibly appealing men with that ruddy, Northeastern skin that wants to shout “sun” and “tropics” but really whispers “gin.”

Which may be why, on that lovely spring morning as I watched Dr. Right leave me, I began to spiral and suddenly found myself formally introduced to the concept of introspection. He’d skulked out the door on Gucci-clad cloven hooves, into the stunning, dappled daylight of disgrace and taxis. And he’d dropped his bags dramatically at his feet, and he’d looked up at me and wiped his brow in that noonday-sun kind of way that men do in deodorant ads and Steinbeck novels. Leaning out our third-floor window, I had said, “Don’t forget this”—and catapulted his prize brass cigarette lighter out, watching as it bounced expensively on the hood of his beloved convertible. And he had looked back up at me, a meaty Teutonic fist clenched in defiance, and said four parting words.

Four words.

“Don’t scratch the enamel!”

To anybody observing him glancing helplessly up at me with his Poppin’ Fresh Dough eyes, his would appear a desperate and soulful plea for one last try, for some kind of reconciliation. It actually wasn’t. And I knew better. I’d seen that fawn thing before. And no way was I going to jump right back into Lake Him. Still, I was the one physically, palpably, and incomprehensibly racked with guilt. Absolutely riddled by it. And that would be why? Why? Why had I spent two years with a man who was so blatantly unable to see the earth’s passage of time as anything other than one long autumn afternoon in Connecticut? And we lived in New York.

Don’t get me wrong: this was a terribly attractive guy. Clark R. M. Wheeler, M.D., wasn’t a brain trust, but he was one of those people with an uncanny sense for what was relevant. He had sort of a cultural suntan. The kind of guy who’d invoke an arcane but incredibly hip name reference—and invoke it disparagingly—at parties. But enough so that people would figure, if he could disparage, then at least he could comprehend far better than they. He’d say things like “That woman there thinks she’s Susan Sontag.” Or he’d deliberately mix up Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Paul Gaultier so people would think film and fashion. How multimedia. Or he’d remind us all at brunch what a profound impact, ya know, the Velvet Underground had had. Dear Nico. And how the mood on Prince Street just hadn’t been the same since Andy died. Of course, privately to me he’d inquire about things like whether Lanford Wilson and August Wilson were actually brothers. Or just cousins. And I remember one evening at a big dinner party hearing him refer to Tony Blair as a technocrat.

I’d pulled him aside and said, “Don’t you Yvette Mimieux me, Clark. Do you even know what a technocrat is?”

“Not at all,” he’d answered, “but nobody here does either, so I’m fine.”

I had genuinely loved him. It was that good, comfortable, this-is-how-it’s-going-to-be love. Born of time, afternoons, and I’m here, you’re here, let’s-make-dinner ease.

And I could say not one word when he left. Not a single one.

Given the world of Marketing & Promotion, which claimed me as an early, willing, postgraduate casualty, I’m not without the blemish of veneer myself. After all, I do write promotional materials for a living. And have always been a little stunned that people paid me (and financed my health and dental repair) just to sit around and dream up ideas to coerce unwitting or distracted people to make purchases, buy magazines, contribute to political causes, and join any number of clubs. I am amply rewarded for creating a huge and growing expanse of wilderness between Americans and their income.

Copywriting is not rocket science, but it does have its own experiential learning curve. I created contests. I dared Americans not to believe that they might have already won. I kept dreams alive because I authored million-dollar sweepstakes. And renewals. And bills. And you-like-this-magazine-why-not-try-this-one? pieces of direct mail. And everything comes Risk-Free, and it all has a Free Gift of marginal value attached somewhere. And the fact is, I had a certain knack for it. It was as if God had said, That fellow? I’ll make him lead a country out of war. Or, That child? He’ll bring hope to Zimbabwe. And then He’d said, That one? The little redhead? She’ll be aces in the junk-mail arena.

Junk mail is one of civilization’s great gifts. It’s a necessary evil for a number of reasons. One, it allows people to live reasonably comfortably in antiseptic midtown-Manhattan co-ops. Two, it saves companies millions, because when they only want to reach, say, five or six million people but they don’t want to reach an additional eleven million people (who’d never buy their product anyway), they simply send out direct mail. It’s perfect. A genuinely targeted way to spend only what they need, to wind up in exactly the right mailboxes.

At lunch with literate, moral types I say I’m in publishing. At cocktail parties, I just go ahead and admit I’m in advertising. And thus, when I met and fell for Clark R. M. Wheeler, M.D., I have to say I kind of knew what I was getting into. I had a pretty good rent-stabilized Glass House myself.

Plus, things with Clark had been coming along kind of swimmingly. We’d met at an auction (my first and last, his 546th) to benefit either Russian dissidents or glaucoma or Kurdish unity, and we had both gotten terribly drunk. Clark lit my cigarette but announced rather boldly that he didn’t want me to think he was one of those guys who went around lighting people’s cigarettes. Not that I cared. He smiled a lot after he said things, as if startled by his own ability to speak, and then he’d look at you like you’d shared some inside joke about his newfound skill. Which I thought was a huge connection for us.

After about three weeks of rather formal courtship, Clark and I entered into an emotional lease agreement. After another three months we were perceived as dull and sweatered.

Until sixteen months later, when he announced that he could no longer deny the woman who had touched his soul. And it turned out, she and I were not the same woman. In fact, she was my very own cousin, a feral, oppressively blond homemaker with a penchant for Joyce Carol Oates, olestra, and Kansas—the band.

And with that, Clark said, he wanted to explore other avenues. Just breezily, like people say they want to reduce their carb intake. And despite the fact that I hoped they’d be avenues teeming with late, machete-wielding bike messengers, I said nothing. I simply affixed both eyes upon him (easier said than done, since I have a bad wandering eye—the left one is frequently at a ninety-degree angle to my nose). I just glared. Silently. Before shedding one tiny, Lifetime Cable–ready tear. Whereupon I began to clean. And then he was gone.

Twenty-eight minutes later I called my psychotherapist, an Andie MacDowell/Nurse Ratched hybrid. I left a whining message on her machine, and she left me one two hours later, saying she’d love to see me, but the Jitney to Quogue was boarding in three minutes—and maybe I should go back home to Philadelphia for a stint, “because you always feel better when you do.” And then she said also not to forget to love myself a little, and also not to forget that I still owed her for January.

So, convinced that this woman might just have a point, and equally convinced that my entire body had atrophied from too much peanut butter directly out of the jar, I decided to get some exercise. So I went for a drive. In a taxi. To Penn Station. And I boarded Amtrak’s Yankee Clipper to Philadelphia. To my mother’s home. Where she, a forthright woman in her seventies—who very definitely still likes Ike—would assure me that this was fleeting. And that somehow all would be well. There would likely be a bubbly tub involved. And I would be offered Shake ’n Bake and other cholesterol-infused Gentile Home Remedy products.

Once back inside suburban Philadelphia’s Main Line, I knew I would be subjected to the gentle ridicule, wishful thinking, and abject criticism that doubles for parental love in so many of these families. I think.

“Mom,” I whined as I walked inside. It smelled of cedar and wet dogs. “Mommm, he left me.”

“Who? That wooden Indian?” She hugged me and I was suddenly, tearily petite.

“Claaarrk. He . . . he—”

“Sweet thing,” she cooed, squeezing me for a long time. “There,” she said. “Not to worry, Lovebug. You know you’re much better off without that Clark. Reading all that Philip Roth nonsense. Hmm. Is your hair lighter? What’s with those little tendrils?”

“He just up and . . . he didn’t even . . . I mean, nothing,” I wailed, again hurling myself like an unwanted medicine ball into her lanky, aproned torso. “This is awful. An affair? That’s the last thing he’d . . . what’m I going to . . . I don’t know what to do!”

“I do.”

“What? What, Mom? What can you possibly—”

“We’ll get supper. And you’re going to feel much better, Miss Pink.” She patted me and strolled over to get a better glimpse of the kitchen’s thirteen-inch TV set.

I continued to blurt interrogatives and demi-expletives, but she’d stopped listening. See, Entertainment Tonight was profiling the leisure activities of pop superstars. Which prompted her to turn back to me and observe:

“And another thing, Lambchop. Say what you will, but that Céline Dion’s got the most beautiful golf swing I think I’ve ever seen.”

I was home. That which Anglo-Saxons call “healing” had begun.

Mother told me to put on lipstick and then we’d be off to dinner. I silently followed her around like a wan Labrador while she turned off lights, shut doors, and made little notes for herself on monogrammed Post-its. She is tall and slim, with pale blue eyes and hair that is quite gray, but I don’t so much see the gray, because in my mind it is auburn. She talks with her hands. She drives cars passionately, swiftly, and efficiently. We sped along Lancaster Avenue, and I recounted a few details of Clark’s departure as I followed the telephone wires in the darkness outside the car window. Finally we pulled into the Merion Cricket Club’s massive red-brick entrance and wound along past the acres of lawn-tennis courts, parking in a huge lot filled with Jeeps and small expensive sports sedans bought to replace now-matriculated children. Once inside the clubhouse bar we ran smack into Thatcher Longstreth, our family lawyer for over two centuries. Mom gently held the back of my neck like one would an unwieldy but valuable trophy statuette.

“Hiya, kid,” said Mr. Longstreth, slapping me hard on the back and permanently lodging an olive in my trachea. “How’s that job? And the big city? Still saying no? And how’s the wandering eye?”

“Oh, hi. Everything’s fine, thanks.” I was now really listless.

“The littlest is back to pay us a visit from the Big Apple!” My mother beamed, and I was relieved by her bland re- mark. This is a woman who might just as easily have said, She’s back to lick her wounds . . . the needless foolish we-told-you-so wounds inflicted by that poseur jackass from Wesleyan with two heads and the stupid haircut and dubious medical degree. The nice Irish lady who had been smiling at me since I was four years old appeared and ushered us into the main dining room for supper. Mom waved good-bye to Mr. Longstreth and steered her Littlest Cub ahead. I kept my head down as we entered, still curious about whether or not the diagonal diagrams on the carpet would ever make me dizzy enough to throw up. They hadn’t thus far, but they were looking like they could.

I behold our club’s cavernous Sistine-esque dining room, and suddenly I am fourteen again. Mom has taken my big sister Meg and my two brothers Malcolm and Eliot here to lunch. Meg is complaining that someone made fun of our family earlier that morning. And surveying the brood proudly, Mother says, “Well, I have four very competent, very attractive children.”

There is a pause, whereupon Meg turns to Mother and says, “You know, I don’t think Elizabeth’s such a knockout.”

My uncle says later that the Lord has given everybody something, and that it’s a good thing He made Meg so astonishingly beautiful because He also gave her the mind of a tropical fish.

Mother now surveyed the dining room, and I wondered when, if ever, I would be able to look around pleasantly like she does, and not think about dying quietly and alone, curled in a walk-in closet, with the tips of dry-cleaning bags tickling my nose. We were seated, and I picked at radishes and celery lingering in easily two inches of water in a porcelain dish. I remembered that most people who drown do so in less than three feet of water. But I don’t remember if that’s because they’re in the tub or because sharks like shallow shoals.

“Lambchop, I know it feels terrible, but you really are better off without him. You just are. I can tell you right now that if your father were alive, he wouldn’t have cared for Clark one bit.” Mom smiled at the waitress, who was waiting patiently. “Just the little filet. Rare, Margie. Thanks.”

“And no veggies tonight, Mrs. Warner?” Margie waited quietly with her pad.

“Certainly not. What about you, Lambchop?” Mom and Margie stared at me.

“Well, um, how’s the monkfish?” I queried.

“Elizabeth, it’s fish. It’s fine.” My mother was exasperated, as if I’d asked Margie to recite Farsi.

So I wouldn’t cry anymore, I quickly changed the subject and told Mother about how I might be accompanying a friend to the Tony Awards.

“Oh, that’ll be fun. Has Pete Gurney got a Tony nomination this year?” she asked hopefully. Mention theater and she’ll always carp about how A. R. Gurney never gets the recognition he deserves. Now that Dick Rogers has passed on. (Although she does concede that Dick Rogers got plenty of recognition.) Gurney is a really big deal for Mother.

“I don’t think there’s a Gurney play up for a Tony this year, Mother,” I admitted, with the same gravitas I would use to tell her that somebody’s nation was too racked by poverty and civil war to send a troupe of athletes to the Olympics.

After a gin-soaked but nostalgic meal, with three side trips to the ladies’ room, where I sobbed off and reap- plied the makeup Clark R. M. Wheeler, M.D., had single-handedly sent streaming down my already raw cheeks, Mother and I returned home. In through the mudroom, which was neither muddy nor roomy. With the cedar and the wet-dog smell and the down vests nobody wears. The house whose internal topography I know so well—all the kids do—that we could each maneuver anywhere through the dark barefoot, with only floor surfaces and the echoes of certain walls and clocks and faulty ice-makers to guide us. Mother suggested we retire to the den for a belt and a visit.

The den reminds me of one thing and one thing only: nature programs. National Geographic. Wild Kingdom. Jacques Cousteau. And that Public Television programming mitzvah, Nova. I think these shows embodied a certain American ideology that my parents were happy to imbue us with. For one thing, they represented triumph from the get-go, beginning as they always did with powerful and heavily orchestrated theme music that invariably reeked of victory over adversity. Then there was the voice-over, taking us through the seasons. The gentle tone, ever assuring us that despite the ravages of winter, all will thaw and spring will come. And when spring—naturally characterized by the feminine pronoun—does appear, her accompanying image on the screen was usually time-lapsed footage of a flower opening, with water trickling soothingly in the background. Then, to further describe the newness of spring, came a shot of four or five clumsy but alarmingly cute cubs—of canine or feline variety—roughhousing, with the gentle reminder that soon enough any one of these frisky little fellas would be large enough to systematically annihilate a small family of unwitting tourists, if provoked and hungry. Leaving nary a blood-soaked ligament.

But what always stood out for me with these shows was a kind of morality. Or its agonizing absence. Because about two thirds of the way through each program, a young wildebeest would get brutally mauled by a group of roving (and presumably delinquent) hyenas. Or a pair of cheetahs would take out an enfeebled gazelle. And I would watch this carnage in mute horror. And the question that always sprang to my lips was why.

“Why? WHY? Mother!?” I had demanded as a child. “Why doesn’t the cameraman step in and save that baby/older doomed animal if they can film it? Why? Why?”

And Mother would always put down her needlepoint and look at me before saying,

“Because that’s nature’s way, Lambchop. That’s nature’s way.”

And I just know that privately she had to be wondering the same thing. And that her response to me was just some kind of antidote to the existential void. And then she’d invariably look at the big wall clock behind me and say:

“Okay, Miss Pink. Isn’t it time for Betty White’s Party?”

Betty White’s Party was our family expression for bedtime. An expression that, I realized some eleven years later on a particularly disastrous date, was not a universally recognized term.

As I retired upstairs that night, Mother pointed out that tomorrow would yield banner opportunities to move on or at least to forget. Soon I wouldn’t even remember any old Clark R. M. Jerk anyway.

“You know, Lambchop, that thing was never meant to be. You’ve got to let him go. You know what they say about a caged bird singing? When you let him go and he’ll come back if he was meant to, but he can’t know till he sings and flies, right?”

“I think I know what you mean.” Then she told me that I should just get busy at the office, where there appeared to be less doom. Of that she was certain.

“You’ve got to keep the accent on the right syl-LA-ble, dearie. Why don’t you just throw yourself into your work? You know, where you don’t ever have to worry about forming close personal relationships?” She smiled, adding, “Oh, and here you go. I couldn’t resist.”

She presented me with a wrapped Lanz nightie. Which made fifteen this decade alone. A great woolly gown to keep the chilliest, burliest lumberjack toasty and impervious to nuclear winter for several unpleasant centuries.

“Thanks, Ma. You’re right.” I kissed her.

“God bless,” she said as I ankled up the stairs.

I considered Mom’s work-immersion advice. I remembered that my boss’s boss had recently remarked that I’d have been considered quite attractive during the Middle Ages. And that it was just a good thing I had hair, what with my features and all.

Nor was I really certain that my mother understood exactly what it was that I did for a living. In the same way that men she knows who were in the war who did anything connected to planes are automatically “fighter pilots” (with whom she will discuss Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo until sunrise). This is exactly why I wasn’t sure she knew what it was I did. And while I do not believe she thinks I am a fighter pilot, she has never once focused on the fact that the endless sweepstakes and renewal notices she gets in the mail were probably authored by her youngest child. I’m pretty sure Mother thought that since I worked for a magazine empire, and since I wrote for a living, I must actually have been a journalist.

Of course she was right about the getting-busy part. Wisest to get back on the plan. So I would become subsumed by my job, forget all about Dr. Right, and feel that sense of serene calm that comes from good old head-in-the-sand hard work. I would be, after all, functioning. And I would find the answer. And it would be direct mail.

I then crawled into one of the mirthless barracks-style twin beds in “my room.” It was, in fact, still my room, even though it too had undergone that whitewashing process that people perform to create a generic guest room when the kids have gone. I know this causes problems for many people. People who feel forgotten and alienated once the space they grew up in (and slept in, wept in, journaled in, played 45s in, and viewed dirty pictures in) has been utterly transformed. Transformed until their beloved sacred spot is no more personal than a “demo sleeping chamber” at Calico Corner. Still, I can take comfort in the fact that mine are actually parents who would have kept trophies displayed even now, if I had ever won any. Looking around, I had to smile, because even though the plaster Christmas hand imprints were gone, I could distinctly make out a small stack of Ranger Ricks on the bookshelf—although My Friend Flicka and Black Beauty had long since been delivered unto grandchildren, replaced now by volumes from Winston Churchill, William Buckley, and Amy Tan.

I noticed a shiny new catalogue on the bedside table. (Editorially speaking, a well-crafted catalogue really can reside comfortably and alone on the summit of direct mail’s Mount Olympus.) I hadn’t authored this particular one, but it was clearly a handsome example of this important genre. What’s not to like about catalogues like these: four-color shiny invitations to a Better Way that will require some fiscal outlay on your part? I am all too happy to invent the bright, customer-friendly worlds of bold colors, attractive copy blocks, and undeniably appealing lives and styles.

On the catalogue cover, in an upbeat, devil-may-care font: this summer. So summer’s upon you. So there’s that. You’re reminded, ever so gently, that you’re quite likely to be stuck in lederhosen and a hair shirt this sum- mer unless you buy some clothes. And damnit, you’ll need that one cotton sweater, color: surf, that’s good for exactly one afternoon when, by golly, you better be sitting Native American–style on a dock talking animatedly about this week’s issue of The New Yorker because—jiminy!—you actually got through it and it only took you seven hours.

Then you open the catalogue up. And behold. Extraordinarily attractive people, seemingly devoid of concern. The kind of young, scrubbed people who, if you asked them about domestic abuse or Kabul or stem-cell research, would probably produce one of those red plastic rings on a stick from a reinforced on-seam khaki pocket and blow a soapy bubble right through it at you. Those khakis that are, of course, available in shale, slate, silt, or schist. And next spring in pesto and alloy and root and hemoglobin and lentil and inlet.

Suddenly you wonder why you don’t have a boyfriend who wears eight layers of plaid shirts all at once. And why doesn’t he bring you the fresh milk that he’s just happily procured from the goat . . . the goat grazing delightfully by your handcrafted knotty-pine and wrought-iron trellis? Why doesn’t he bring that milk to you as you’re reclining languorously atop that downy, sunlight-flecked bed that is covered by a bold, colorful quilt? The quilt you stitched last summer while you laughed happily at your Adirondack fishing hideaway with your good, straight, white, appealingly liberal friends before joining forces to make a healthy but robust meal together filled with laughter, humility, and pointed intellectual debate. And even when you had a flat tire it was fun, because those guys you’re with—the ones with all the plaid shirts—see, along with the fact that they all have doctoral degrees in Semiotics and a profound understanding of Mahler and can explain the difference between wicker and rattan, why, they’re also uniquely qualified to change a tire in less than ten minutes, plus they can operate a forklift, and they’d also ably run with bulls in Pamplona.

Which is when I closed the catalogue, took three Benadryl sinus tablets, and enjoyed a hot mug of Sambuca. Before I drifted uneasily but antihistaminically into raglan-sleeved, garment-dyed sleep, a cursory check of my answering machine in New York revealed that Dr. Right had indeed phoned, but simply to let me know that he was returning to retrieve his nine iron and his “Paul Stuart Elements of Style” CD-ROM. And he’d phoned, he said, so as not to startle me. But now, of course, nothing startled me, and as I considered the gyrations and machinations of the human spirit, I came to realize that it was all, really, just nature’s way. Just nature’s way. Besides, I was eating. And frequently in top-flight restaurants. And it dawned on me that perhaps one can coexist peacefully with—or at least graze alongside—one’s black heart and empty life.

The following morning I returned to New York with renewed vigor. Sometimes you just need a little trip home to see that once we overcome the Gaza Strip of childhood, anything’s surmountable. Even Susan Sontag.