Excerpt

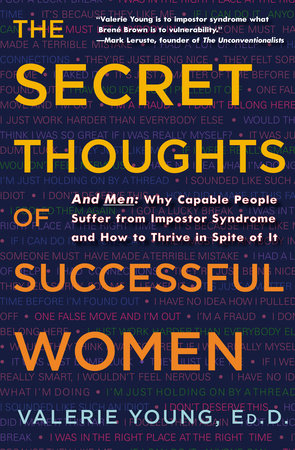

The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women

The Perfectionist’s View of Competence

For the Perfectionist, there is a single focus, and that is

how something is done. Your competence rule book is quite straightforward.

I should deliver an unblemished performance 100 percent of the time. Every aspect of my work must be exemplary. Nothing short of perfect is acceptable. When you fail to measure up to these unrealistically high standards, it only confirms your feelings of impostorism.

Some Perfectionists hold only themselves to these exacting standards, while others impose them on other people. At home the latter might sound like this:

No, honey, that’s not how you fold a towel—this

is how you fold a towel. There is a right and wrong way to do everything, from packing the car for vacation to preparing a project plan. Since no one can measure up to your precise standards, your motto is

If you want something done right, you’ve got to do it yourself. When you do delegate, you are often frustrated and disappointed at the results.

To be clear, perfectionism is not the same as a healthy drive to excel. You can seek excellence without demanding perfection. More important, non-Perfectionists will attempt difficult challenges and feel okay about themselves afterward—whether they succeed or not. And they’re flexible enough to redefine success as the situation warrants. That’s not to say they aren’t disappointed if they fail. But as long as they gave it their best shot there is no shame. Not so for the Perfectionist.

Indeed, for you just the opposite occurs. Quality-wise, Perfectionists always go for the gold, the A+, the top spot. Anything less and you subject yourself to harsh inner criticism, often experiencing deep shame at your perceived “failure.” Precisely because there is such shame in failing, you may avoid altogether attempting anything new or difficult. After all, getting things “right” takes a lot of effort, energy, and aggravation. It’s much easier not to even try than to put yourself through those paces and risk the humiliation of coming up short.

Even if you are extremely motivated, success is rarely satisfying because you always believe you could have done even better. You get into a good school but are disappointed because you could have gotten into a better one. You deliver a top-notch presentation but kick yourself for not remembering to make some minor point. You broker a major transaction only to wonder if you could have struck an even better deal.

Perfectionism is a hard habit to break because it’s self-reinforcing. Because you do overprepare, you often turn out a stellar performance, which in turn reinforces your drive to maintain that perfect record.

But it’s a huge setup. Because when you expect yourself and your work to always be perfect, it’s a matter not of

if you will be disappointed but

when.Perfectionism is not a quest for the best. It is a pursuit of the worst in ourselves, the part that tells us that nothing we do will ever be good enough—that we should try again. —Julia Cameron, author, poet, playwright, and filmmaker

Competence Reframes for the PerfectionistWhat you consider to be merely “satisfactory” work probably far exceeds what’s actually required. That’s why it is so important to reframe your current thinking about things like “quality” and “standards.” I spent twenty-five years working with people who aspired to be their own boss. As a rule, the women were far more likely to wait for everything to be perfect before they’d launch. They’d endlessly tinker and tweak and adjust, making sure everything was just so, but they never began. In the end these high-minded notions of “quality standards” and “getting it right” equal paralysis.

On the whole, male entrepreneurs operate from a very different definition of quality. The mantra repeated by speakers at the numerous online business seminars I’ve attended always comes down to some variation of “You don’t have to get it right, you just have to get it going.”

Some business gurus go even further, telling procrastinating Perfectionists that “Half-ass is better than no ass.” The wording may have been crass, but the fundamental truth remains: If you wait for everything to be perfect, you’ll never act. Whether it’s a product, a service, or an idea, you have to put version one out there, get some feedback, improve on it, then create a new and improved version from there. You can always course correct as you go. But at some point you must decide it really is good enough.

If you work in the corporate world, medicine, or academia, you may be understandably turned off by advice like “Half-ass is better than no ass.” So what if we repackage it into something more respectable, like a paradigm? As it turns out, the software-development world not only shares the basic mindset of my Internet marketer friends, but the concept even has an official-sounding name. Paradigm creator James Bach calls it “good enough quality,” or GEQ.

Bach’s article “Good Enough Quality: Beyond the Buzzword” appeared in a well-respected publication dedicated to advancing the theory and application of computing and information technology. In it he asserts that GEQ is standard operating procedure in the software-manufacturing world, explaining that “Microsoft begins every project with the certain knowledge that they will choose to ship [a software product] with known bugs.”2 This is not a jab at Microsoft or, for that matter, any software company. Rather, it’s recognizing the reality that any manufacturer in the technology sector must operate with a degree of uncertainty.

To be clear: The principles of GEQ—or “Half-ass is better than no ass”—have nothing whatsoever to do with mediocrity. Nor are they about providing the minimum quality you can get away with. None of the seven- and eight-figure-earning entrepreneurs I know got rich selling schlock. And Bill Gates and Steve Jobs did not build the two dominant technology companies in the world by putting out inferior products. For a product to be considered “good enough,” Bach insists it must still meet certain criteria. To guide those efforts, his good-enough quality paradigm includes six factors and six “vital perspectives.” Notably, being perfect is not one of them.

None of this is to say that you have to relinquish your quest for excellence or do things willy-nilly. What it does mean is, with some obvious exceptions such as performing surgery or flying an airplane, not everything you do deserves 100 percent. It’s a matter of being selective about where you put your efforts and not wasting time fussing over routine tasks when an adequate effort is all that is required. If you get a chance to go back and make improvements later, great—if not, move on. There’s a reason why scientist and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov is proud to describe himself as a “non-perfectionist,” telling fans, “Don’t agonize. It slows you down.” With five hundred books to his name, I’d say he’s on to something.

Reframing perfectionism is also a smart career move. If you work with other people, there’s a good chance that your constant need for everything to be just so is a problem for them too. A project manager at IBM told me things got so bad with one perfection-obsessed team member that she finally had to pull her aside to say, “Knock it off. You’re slowing the whole team down.”

Rather than enabling your success, perfectionist thinking is actually a gigantic barrier. The late author Jennifer White said it best: “Perfectionism has nothing to do with getting it right. It has nothing to do with having high standards. Perfectionism is a refusal to let yourself move ahead.” It’s that last line that is so powerful.

It will take some practice, but you really can learn to appreciate the virtues of non-perfection. The most beautiful trees are often those that are the most misshapen. Many of the most profound scientific discoveries were the result of mistakes. I once read that in some Islamic art, small flaws are intentionally built in as a humble acknowledgment that only God is perfect. How stupendously boring life would be if every wave was the perfect wave, every kiss the perfect kiss. There is utility, beauty, and grace in non-perfection. Learn to embrace it.