Excerpt

Rest in Power

Chapter 1

Sybrina

Our Lives Before

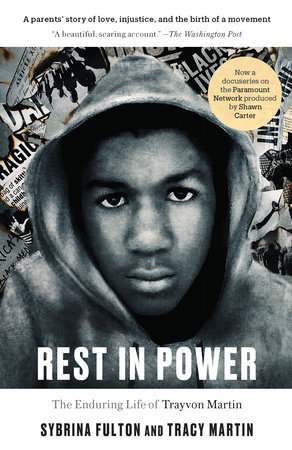

Who was Trayvon Martin? I’ve been asked that question a million times since his death. In death, Trayvon Martin became a martyr and a symbol of racial injustice, a name and a face on T-shirts, posters, and protest signs.

When he was alive, of course, he was none of those things. He was simply a boy, growing into a young man, with all of the wonder and promise and struggle that that journey entails.

What else was he? He was loved. Trayvon had struggles—academically, even behaviorally at times—but he loved his friends and family, sports, music, and his dreams of flight. And he saw that love returned and those dreams coming within his reach. In other words, he was a boy, and because he was mine, he was (along with his brother) one of the most important and cherished boys in the world.

His story begins with my own.

My mother named me Sybrina with a y. When I was born, Sabrina with an a was a very common name. “I wanted her name to be different,” my mother said. And so it was Sybrina, and if our given birth name is an indication of our destinies, then from the beginning I was blessed and cursed to stand out.

I was born in Miami, but we soon moved to Opa-locka, which was a working-class Miami suburb. My mother worked at the post office as a clerk. My birth father was a longshoreman, who died young from heart failure. In 1978, when I was eleven, my mom remarried, to a police officer who worked on the streets of Miami. I was a flower girl at my mother’s wedding, dressed in a flowing ivory gown, hair styled up in a bun, and happy. My stepdad was a powerful, strict and taciturn, presence in our house. We lovingly called him Dad.

I was the baby, the youngest of four children, with two brothers who always looked out for me; an older sister; and two stepsisters. We weren’t rich, but my parents made sure we were all well provided for. We never had to worry about our electricity being turned off or not having a place to stay or a car to drive. We had big Christmases, went on summer vacations, and always attended church on Sunday. We were taught the importance of work. My parents had good jobs and high expectations, and they expected me to get a good job, too. Nobody gave anything to me. I had to earn and work for everything I wanted.

We lived in a predominantly black neighborhood, although within the neighborhood there was a blend of different nationalities: Cuban, Jamaican, Bahamian, and Haitian. Back then, in the 1970s, Opa-locka was a paradise. Children played everywhere: in the street, at the school, in the park. There was a house where a lady sold candy and a corner store where we would get soda and chips. Early on, my mom and dad taught me and my two older brothers the proper way of doing things. As soon as I came home from school, I had to change into my play clothes, and before I was allowed to go out and play I had to clean up and do my homework. Then and only then would I be allowed to go outside. We’d play tag and run up and down the street. Even then my dad, the disciplinarian policeman, gave us our perimeters: we had to stay within the two stop signs on our street.

Opa-locka was changing during the 1970s, like a lot of America at the time, suffering from an influx of drugs and an escalation of street violence. Despite that, my mom and dad created a loving and safe environment for us: what went on outside our doors was different, separate, foreign. There were problems raging out there, but we didn’t see or feel them. We were protected. I never saw the violence; I never saw drugs.

By the time I was in my teens, my dad had become a detective, but he didn’t bring the energy of his job home. He was always polite with us, but still very strict. I had a curfew. People couldn’t just walk through our home. Sometimes I’d go to other people’s homes and their parents would allow the children’s friends to just walk all over the place. My friends had to be in the same room where I was: if I was in the den, they had to be in the den.

And, of course, I wasn’t allowed to start dating until I was sixteen.

I felt comfortable in the easy flow and ordinary rhythm of our humble community, but the truth is I didn’t want to be like everybody around me. From a young age, I craved something different, and for me education was the path to a less ordinary life. In middle school, I pursued a series of passions, always backed by my parents. I took classes for acting, etiquette, and modeling, and even learned how to play the piano and clarinet, and I also ran track. When I graduated from high school, there was no question that I would attend college.

My dream was to attend college in Tallahassee, where I had friends—until my older cousin told my mother that everybody went there. So she decided that I needed something different.

“I’m not sending my money—or my daughter—there,” my mother said. “Sybrina, pick another school.”

I flipped through a book of colleges and, almost at random, settled on Grambling State University in Grambling, Louisiana, a place I had never visited, where I knew no one, and that, honestly, I knew nothing about. I just picked it because I wanted to get away from Miami, do my own thing, be my own person, and follow my impulse to do something different. I had never been away from home before, without my parents, other than to attend summer camp.

My mother, impressed with my determination, approved.

My mom, my Auntie Leona, and my brother Mark drove me to Grambling. When we arrived, I checked in to the freshman dorm and got my room key. My family and I went upstairs to my standard dorm room: two beds, two desks, four walls, small space. Okay, it’s just like summer camp, I thought. My mom, my aunt, and my brother helped me move in. We cleaned up everything, made up my bed, plugged in the clock, unpacked my clothes, and hung them in the closet.

It was time to say goodbye.

We all hugged, and Mama kept up a patter of encouraging talk as she slowly moved toward the door: “Sybrina, you will be fine”; “You’re going to do great”; “You’ve always liked to do things on your own”; “You always did like to be adventurous.

“This is awesome and I’m so proud of you,” she said at last, as they were leaving.

I walked out after them down to the sidewalk and watched their car start to pull out, when suddenly it all hit me at once like a big wave: this wasn’t a good thing. In fact, it was the worst thing in the world. I started sniffling. Then crying. Then boo-hooing. Then screaming. Making all this horrible noise in front of the entire freshman dorm. I don’t know where it all came from, but soon I was screaming so loud that my family could hear it from their car, and they turned around and drove back to where I stood. My mother popped open the door and came over to me.

“Sybrina, what’s wrong with you?” my mother asked.

I felt like a puppy that had been left alone in the woods. I looked at her with pitiful eyes.

“Sybrina, look at all these people looking at you!” my mother said, gesturing to the students and parents now staring at us.

“I don’t care, I don’t know these people,” I said, getting back into the car with them, ready to drive away from Grambling forever, and go back home. Instead, they took me to Captain D’s, a fast-food seafood restaurant, for lunch.

“Oh my God, I cannot believe you are doing this,” my mother said, because I’d always been strong. But in that moment I realized how much family really meant to me—not just the idea, but the physical presence of family, the closeness, the way the people you love can create a kind of soft, gentle barrier around you that makes everything seem easier. When my family left me, alone in that strange place, that lonely place, I felt a chill wind, a sense of isolation I’d never known before. After a while I calmed down and slowly went back into the dorm. A year and a half later I was still homesick, and when I came home for Christmas break, I never went back. I enrolled in the University of Miami for one expensive semester, before transferring to what was then called Florida Memorial College, where I majored in English with a minor in communications.

My ambition was a career in television, either as a reporter or someone who worked behind the scenes, but when I interned at a Miami television and radio station, Channel 10 and 99 Jamz, everyone told me, “You’re going to have to leave Miami to go to one of the smaller markets to get more experience.”

I thought about it, but worried—maybe this is going to be just like Grambling, homesick all over again.

I decided I wanted to remain close to home. In 1989, I left college to do what I had always done: go to work. My first full-time job was working for Miami-Dade County as a console security specialist.

I sat at a desk that faced a wall of small TV monitors, fifty in all, each connected to a closed-circuit camera around the county. I was also given seven different two-way radios that connected me to various nearby security companies. My job was to monitor the cameras and alert the security companies by radio whenever I saw something suspicious or whenever an alarm went off. So I kept an eye out for anything I thought might be suspicious—never targeting a demographic category. I learned how to size people up rather quickly, without having to resort to simplistic profiling.

It was a job in security, I suppose, except it wasn’t dangerous; occasionally there would be a minor break-in or other petty crimes to report, but mostly my shift included homeless people sleeping where they shouldn’t, vandalism, and cats and dogs triggering false alarms. It was a good, solid job. I was in my twenties. I was dating and had been proposed to twice. I felt like I was at the beginning of something; the start, maybe, to a life that worked, surrounded, still, by the family I loved in my hometown.

It wasn’t love at first sight. But Tracy Martin grew on me. I met him at the Miami-Dade County Solid Waste Christmas party in 1993. I was still working for the county, but had been promoted to a code enforcement officer, writing tickets for violations, mostly to people dumping trash in front of thier homes. It wasn’t a glamorous job, but it offered stability. I was still good at quickly sizing people up. But when Tracy’s brother, Mike who worked as a truck driver for the county, brought Tracy over to meet me, he wasn’t easy to size up or understand.

Tracy was very tall, thin, and really lean. When he said, “How you doin’, Sybrina?” his baritone voice, which was inflected with a thick accent from a faraway place—well, not that far away: he told me he was born in Miami but raised in East St. Louis. But it wasn’t his voice that drew me in: we seemed to have clicked from the start. He was friendly and funny, and I just felt, somehow, although I still can’t figure out why, I just felt we had met before.

He asked me out a few weeks later. Everything about Tracy Martin was different. He was hilarious and gentle, but also bold and self-confident. His already impressive height was topped by a high-top fade. I liked him, and came to love him, enough to say yes when he proposed. We were both twenty-seven.

On June 11, 1994, we were married in a big Miami wedding, filled with friends and family, at a banquet hall. We moved into a small, two-bedroom apartment. In the beginning, it was Tracy, my son Jahvaris, then an active and intelligent four-year-old bundle of joy, and me, beginning a new life of hard work, faith, and family.

Our baby, Trayvon, was born the following year, on February 5, 1995. My mom and Tracy’s mom were with Tracy and me in the delivery room. I wasn’t asleep, just relaxed from the anesthesia, and in that state I remembered the prediction of a psychic I had visited some years before. I had gone with a friend, thinking I’d only wait for her while the psychic performed her reading. When we got there, the psychic looked at me, and even though I was at the back of a line of people outside, she took me by the hand and said, “I’ll read you first.”

She was a middle-aged Puerto Rican woman wearing a bright-colored dress covered in gold beads, and she led me into her reading room. She began shuffling tarot cards and then placed them down on the table. She then took my hand in hers and started peering down at my palm.

She told me she could see my future clearly. “You’re a strong person, ambitious, very spiritual, and you will live a long time. You care about people, like to help people. As for children, you’ll only have boys, never girls.”

I wasn’t sure if I believed in fortune tellers, but I sensed that what she was saying was true and felt a quick surge of mixed emotions. I had always been close to little boys—everybody in our community seemed to do so much for little girls—teaching them, keeping them safe—and I felt that boys needed someone on their side, too. But, of course, I also knew that black and brown boys had a harder struggle ahead of them—not only with the temptations of drugs and crime, but just to get the basic things that should have been theirs by right: education and employment. So I was always there for my two brothers and my male cousins and nephews. And now I promised myself that I’d always be there for my son, Jahvaris, and also the baby that was now pushing to escape my womb and come out into the world.

Trayvon came out screaming. After they cleaned him off and wrapped him in a blanket, the nurse laid him on my chest and I thanked God for this miracle, this ultimate blessing. I could feel his heart beating so fast, right alongside mine, so close that it made me cry. Then and there, I made a promise: to do my best for this child, as a mother, an example, a counselor, and a friend.