Excerpt

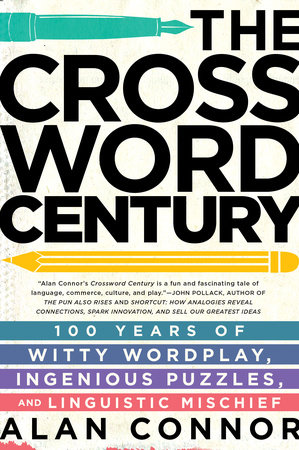

The Crossword Century

INTRODUCTIONThis is a book about having FUN with words. And if you’re wondering why that word is in capital letters, all will become clear.

And it’s a very particular form of fun with words: one that involves jumbling and tumbling them into eye-pleasingly symmetrical patterns and making riddles, jokes, and poetry in the form of crossword clues. A love of crosswords is also a love of language—albeit a love that enjoys seeing the object of its affections toyed with, tickled, and flipped upside down.

Crossword puzzles are a silly, playful way of taking English and making it into a game. They have been doing so since December 21, 1913, when the world’s first crossword appeared—although lovers of language had been deriving pleasure from wordplay long before then, of course. However, it was the crossword that came to supersede all other puzzles. It has become a cornerstone of almost all newspapers and, for many, a fondly anticipated daily appointment.

The crossword today looks quite different than that first puzzle—or that should perhaps read “crosswords today” so as to encompass the baroque creations seen in Sunday papers, the strange mutant British form known as the cryptic, and all of the themed and jokey variants on offer on any given day.

What they have in common is the pleasure of identifying what the constructor is asking for and seeing the answers mesh with one another until the puzzle is finished. For a century, the worker has whiled away journeys and parents have passed on tips and tricks in the hope that each grid tackled will be correctly filled.

In The Crossword Century, we’ll be looking at the playfulness, the humor, and the frustration of the crossword in all its forms, and how the world of the puzzle has overlapped with espionage and humor, current affairs and literature. We’ll see fictional crossword encounters, from The West Wing to The Simpsons, and we’ll see crosswords from the real world: the one that seemed to predict the outcome of a presidential election and the ones that appeared to be giving away the secrets of the Second World War.

We’ll look at how clues tantalize those who are addicted to puzzles by sending the solver on wild-goose chases, by being sweetly silly and soberly serious, and by stubbornly withholding their real meanings until the penny drops.

And we ask questions about the experience of solving: Why do some people try to finish crosswords as quickly as possible? Can computers crack clues? And does puzzling really stave off dementia?

As for how to read this book, please feel free to treat it like a puzzle. That is to say, you can start at 1 across and work sequentially, or you can dive in and out and follow your instincts. The chapters are in two sections: The ACROSS entries look at the creation of puzzles and the strange things that can go on within clues and grids, while the DOWNs describe what happens to the crossword once it escapes into the world and meets its solvers.

Like the British man who created the first crossword in New York, we’ll be crossing the Atlantic Ocean—a few times, in fact—and I humbly hope that along the way I might persuade you that the baffling-looking British cryptic is a lot more enjoyable than legend has it.

Are you ready for FUN?

PART ONE

ACROSS FALL IN A GARDEN, DEPICTED? GENESIS

How the crossword first appeared in 1913 and became an overnight sensation in 1924

Newsday’s crossword editor puts it best. “Liverpool’s two greatest gifts to the world of popular culture,” writes Stanley Newman, “are the Beatles and Arthur Wynne.”

The comparison with the Beatles is on the money—or, to use a more British locution, spot-on. Like the music of the Fab Four, the crossword is a global phenomenon that is at once American and British. But while the Beatles are known wherever recorded music is played, Arthur Wynne’s name remains unspoken by almost all. Who was he?

Well, he wasn’t the Lennon or the McCartney of crosswords; we’ll meet them soon enough. He was perhaps crosswords’ Fats Domino: a pioneer who would see his innovation taken by others to strange, often baroque mutant forms and variants.

Not that this was how Wynne saw his career playing out when he became one of the forty million people who emigrated from Europe between 1830 and 1930, and one of the nine million heading from Liverpool for the New World during that same period.

The son of the editor of The Liverpool Mercury, Wynne was—at least initially, and in his own mind—a journalist. He spent most of his newspaper career working for the empire of print mogul William Randolph Hearst. His legacy, though, was not a piece of reporting, and it appeared in the New York World, a Democrat-supporting daily published by Hearst’s rival, Joseph Pulitzer.

As a kind of precursor to the New York Post, The World mixed sensation with investigation, and it was Wynne’s job to add puzzles to the jokes and cartoons for “Fun,” the Sunday magazine section. He had messed around with tried-and-tested formats: word searches, mazes, anagrams, rebuses.