Excerpt

Phoenix

When I was a little kid, I knew that my brother was lucky. He could stay up late. He could shave. He had a Remington .22 rifle. He was the Master Councilor of the local DeMolay Chapter. He could lay his hands on a dead car engine in the morning and have it purring like a tomcat by midafternoon. When he walked out of our house, he could reach up and touch the top of the doorway, a high, faint smudge offering constant proof. He was lucky in everything--even his looks. He wore button-down shirts and alpaca sweaters, pegged slacks and suede desert boots. He had dark hair and a shy smile--my sisters' friends said in whispered, conspiratorial giggles that he looked like Ricky Nelson--and he smelled of Old Spice, or sometimes motor oil, or sometimes both. But most of all, my brother was lucky because he could go wherever he wanted, and he could go there in his car, a forest green 1950 Chevy two-door with Moon hubcaps and tuck-and-roll upholstery. John was eleven years older, and to me the keys to his car seemed the keys to the world.

++++

Once, a radio station in Los Angeles ran a contest, and whenever you heard a cascade of falling coins, you were supposed to call in. If you were the right caller, you got to guess how much money was in the kitty, and if you guessed right, to the penny, you won it. The caller would guess, and the disc jockey would say, "Puh-

leeze repeat that!" After the caller repeated the amount, a buzzer would go off, and the disc jockey would say, "I'm

sorry, that's too . . .

low." Or too high. The idea was to listen often and zero in on the amount.

John listened, but not often. At the start of the contest, he guessed a number, wrote it on a piece of paper, and tossed it on the dresser in the bedroom we shared. On that dresser he also kept his wallet, his car keys, his Marlboros, his Old Spice aftershave, his spare change (which he often gave me), a few .22 cartridges, and a black Swank jewelry box where he kept his tie tacks, cuff links, DeMolay pin, and a ruby ring that our grandmother had given him.

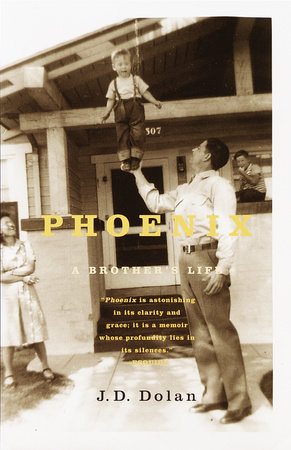

After he died, I ended up with some of John's things: a stack of his clothes, a few of his automotive tools, a camera he'd bought in Okinawa, and the jewelry box. Its contents hadn't changed much in twenty-some years. The tie tacks and cuff links were tarnished. The ruby ring was gone (he'd found out it was just red glass). There were some lapel pins from the desert races he'd finished, his Rifle Expert medal, an old key with a Chevrolet logo. Under a tray in the jewelry box I discovered a photograph of our oldest sister, Joanne, at her wedding; grade-school photographs of Janice and June, who were the third and fourth oldest, respectively; also a photograph of me, the youngest, when I was little, and one of our parents from a time before I knew them, when they were still, from the looks of it, in love.

Another photograph, a small one of my brother and my father, still filled me with a kind of grinning wonder. In this one photograph, my brother's about two and my father's in his early thirties. My father is standing in front of my grandmother's house with one arm stretched out high, and my brother is standing in the palm of his hand. I remember looking at that photograph when I was little and saying, "And

who's that little boy? And

who's that man?" When they told me, I accepted it the same way I did when Dad would pull quarters out of my ear or when John somehow knew just when a red light was going to turn green. I knew it was some kind of trick of the adult world, and I played along.

John called the radio station a few times but couldn't get through. He didn't have a lot of time to listen to contests; he was working overtime as a supermarket clerk and saving his money for--though it didn't seem possible--an even

better car.

I listened to the radio station every day after school and kept track of the contest. With each call, with each wrong guess, it seemed John was that much closer to winning.

One day, as I rode with my mother to the supermarket in our Oldsmobile, I switched on the radio. I sang along to Ricky Nelson's "Travelin' Man," then quieted down when I heard the familiar cascade of falling coins. The contest! This was it! A woman caller made a guess, and the disc jockey said, "Puh-

leeze repeat that!" Something about that number was familiar, and as she repeated it, I screamed, "That's

John's number!" My mother--nervous in her menopausal years--nearly ran the Olds into a parked car. She started yelling at me, but all I could hear just then were the sounds of bells and whistles, and an even greater rush of falling coins.

The radio station played that winning call over and over the next few days. That winning number, John's number, was, I thought, fixed in my memory. But I've forgotten it, just as I'm beginning to forget John's voice. Not surprisingly. He didn't talk much to begin with, and it's been eleven years since his death, and for the last five years of his life he wouldn't talk to me, then he died.

John took the news of the contest, as he did most news, with a shrug. He seemed to have, even in those days, a belief that life was somehow rigged, that even with the right numbers he was destined to lose.

That isn't the way I saw it. But for a phone call he'd won that radio contest. He could work automotive miracles. He could reach impossible heights. He looked like Ricky Nelson. He had the keys to the world and the gas money to get there. My brother was lucky. And I knew that soon, very soon, his number would come up.

++++

His number came up a few days before Christmas in 1965. His draft number. John was ordered to report on January 4, 1966, for induction into the United States Army.

I was thrilled! My brother loved to watch the movie

Sergeant York and the TV show

Combat, and therefore I loved to watch them too. I knew my brother would be shrewd like Gary Cooper and tough like Vic Morrow. And when he came home, I knew my brother and I would be just like the TV show

Route 66--two guys driving around the country in a Corvette convertible in search of excitement. I knew this because John had sold his forest green 1950 Chevy two-door and, with all of his savings, bought an immaculate red 1958 Corvette convertible. The countless TV mythologies of my childhood--shy teen idols, patriotic soldiers, free spirits in fast cars--had become one, it seemed, and achieved flesh and blood in my brother.

++++

The afternoon before Christmas, John waxed his car out on the driveway, covering it with whorls of pale greenish wax until the car looked like a ghost of itself. John didn't like to do his waxing in bright sunlight--partial shade was always better, he said--but wanted to give the car one last coat before he was drafted; besides, this was only winter sunlight, bright and weak, the kind that looks warm but isn't. As he slowly rubbed away the dried wax with the folded cheesecloth, the red Corvette began to shine like a Christmas tree ornament.

Our ash tree in the front yard had been steadily losing its leaves for the last week, and the dry brown leaves were falling thick as snow on our dry brown lawn--which made for great sliding. I hid behind the variegated ivy that framed the front porch, a good toy soldier in one hand, an evil toy soldier in the other: waiting until just the right time. Then I made a run for the spread of leaves and shrieked like a dive-bomber, and then became the bomb and hit the leaves sliding, and the leaves became smoke--there were screaming and machine-gun fire!--and gradually, you could see the good soldier rising heroically from the rubble. With my sneakers I stubbed the leaves back into place, then skipped across the lawn to the front porch and hid behind the ivy again, good in one hand, evil in the other, and waited.

When our father was due home from work, I sat on the fire hydrant at the corner until I saw his old yellow-and-white De Soto in the distance. Then I crossed the street, and he pulled up and stopped--our daily routine--as I climbed onto the big chrome bumper and held tight to the hood ornament, a bust of the helmeted De Soto himself. With me clinging to the warm hood, my father drove slowly past our yellow tract house, then sped up slightly as he made the U-turn and pulled up in front, swirling leaves, braking evenly until the last few feet, where he stopped the car with a little jolt, and I let go of the hood ornament and, for a moment, could fly.

John watched, grinning, from the driveway.

As my father walked toward the house, I trotted alongside, carrying his old beat-up briefcase and wearing his smart Greyhound cap, which fit my head like a tent.

John nodded hello and wiped the sweat from his forehead with the back of his hand. He seemed to be contemplating his wax job.

Dad nodded hello back, then veered over to the driveway beside John. They didn't look at each other, only at the car, and probably at their elongated reflections in the mirrored finish.

"Looks good," Dad said.

This was a tense moment. It had been months since the two of them had said anything more to each other than a grumbled "hello," and usually they didn't even say that much. I didn't understand what all of this was about, just that it had started when Joanne stayed out past her curfew and was ordered by our father to move out. John had been mad about it, and my mother had been nervous, and Janice and June had begun a turf war over the new space this opened up in the big bedroom that until then the three girls had shared pretty happily.

I set the briefcase on the lawn, took off the Greyhound cap.

John wiped a speck of wax from the door handle. "Well," he said, "it'll help protect it."

Dad looked at John and said, "You're not going to leave it out here, are you?" as if his greatest worry about his oldest son getting drafted was that his son's car would be prey to the elements.

John shrugged at this hopeless situation and said, "And the battery will probably go dead," as if his greatest worry about getting drafted was whether his car would start when he got back.

At the time, those were probably my greatest worries, too.

My father shook his head. "No. No. Keep it in the garage. I can start it up once a week. I'll keep an eye on it."

John didn't say anything, but I could tell, from the way his shoulders dropped a little, that he was relieved.

My father picked up the briefcase, took the Greyhound cap from my hands, and said, walking away, "I'll tune it up before you get back."

With John and Dad on seemingly good terms again, the world seemed a wonderful place, a lucky place to be alive for. I went back to playing in the dead leaves and, once exhausted, lay there on my back and stared up at the immense blue sky and the faint high clouds, and as the clouds moved it felt as if the earth was turning. I could see the snowy peak of Mount Baldy, which was usually hidden in smog but now seemed to stand out in high relief on top of the Cannons' house across the street. John kept working on the Corvette, vacuuming the interior, wiping down the dash, polishing the gauges. He'd turned on the radio, and Elvis sang of blue Christmases and Bing sang of white ones. It was getting dark, and one by one our neighbors' Christmas lights came on, then ours did, and in Hollywood, probably at some movie premiere, searchlights fanned bars of light across our sky. I heard something overhead--it sounded as if the sky was humming--and finally I saw it, just another ordinary miracle: the huge silver blimp cruising the San Gabriel Valley in preparation for next week's Rose Parade, its side spelling out the truth in giant spotlighted letters: GOODYEAR.