Excerpt

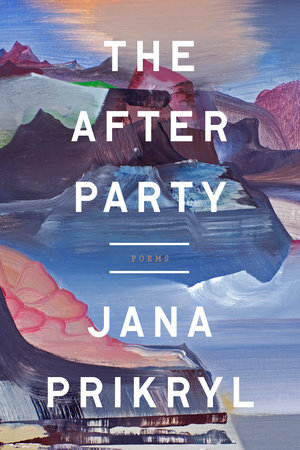

The After Party

Ontario Gothic

1.

The dwarf maple caught my attention

in an ominous way, its purple,

its deep purple leaves shredded gloves

that gesture “Don’t worry, don’t worry,”

among floating albino basketballs of hydrangea

among other things the people landscaped

like fake lashes round the top of the eye

that then all summer takes in clouds

and anything else passing over, including

one has to assume

the neutral look

on a passenger’s face glancing down from a window seat.

2.

Halfway there he squeezed between the shoulders of the seats

to join his wife and me in back. I need hardly tell you

what a stretch it was, wedging my arm between the driver’s seat and door

to steer with the tips of my fingers,

sidewalks in those parts just wide enough for a car.

Why he wanted me to take the wheel

I was too busy not getting us killed

to unravel; there was the traffic, a thing

coming at us with its mouth wide open, and in back

the two of them

whispered in their corner,

taking up very little space,

less than was right,

and then less and less, gasping at the joke he’d set in motion.

Argus, or Fear of Flying

A seagull at home in this valley steps into air

above the river. I’d like to follow

it holding the wind to account while flinging

itself out into it. Remove in reading

and being the music when you listen--

not that you moved back but forward into

remove--saw you off a wall patched with lichen,

consortium of air and electric currents

it’d be difficult to itemize

expressing you across the river.

It deepens like a mind accruing images.

I keep the beat, the tune a repetition,

indifferent its source or whether

rock and roll or country, junkier the more

immense, as with all the airborne arts,

and you keep your distance, convexity,

of feeling, and relations of the third person

vis-à-vis a situation.

It’s crucial to no more than misplace

claims on what might go down with the pilot’s

resourcefulness--it cannot look too

casual--faculties both stirring up

and yielding to motion bestowing lift.

The statues of Hermes littering Europe

with little fins at head and feet don’t conjure

the fact articulated through my limbs

when I read about Zeus flying him in

on winged sandals to murder the diligent

freakish strangely beautiful giant

tasked by the jealous wife with guarding

the innocent mistress--you see there’s always

demand for aviation--in which the god’s

center of gravity over his lofting

feet emerges as something palpable,

autonomous disc near the pelvis

of an ally that’s never not mobile.

Pillow

How solitary

and resolute you look in the morning.

A stoic in your cotton sleeve.

Do you dream of walking out

rain or shine

a truffle balanced on your sternum

and passing me on the sidewalk?

Or is that a smile

because you interpret nothing

and statelessness is where you live?

How calmly you indulge my moods.

See you tonight, by the sovereign chartreuse

ceramics at the Met.

Let’s hear what you’d do differently.

Tumbler

It was too much

to hope for to

hope we would know

when too much was

too much to hope

for.

New Life

From the fields of a calendar, its snow

packed firmly into squares, I farmed you.

Following some paperwork you shipped west

and I flew home economy.

An interval like summer passed before a van found my house

and tilted you off the dolly.

Tucked behind hedges and twilight, with a screwdriver

I pried the lid and under

petals of bubble wrap

your eyes open,

blue as an infant’s

and equally foreign.

That your English came back as fast

as it did was more than anyone could’ve asked.

You soon made friends

just as I’d predicted.

You sleep in the spare room--no closet or chair

but a window onto something green and unconflicted.

Afternoons were tennis, sandwiches,

and drills recalling the yellow bike, the seven stitches.

I know it tires you.

Mustn’t overdo it.

Your memory worked pretty well

considering the mirror time put to it.

In thinking back you’ll try to invent

the future: you see us growing ancient,

say, twenty-nine, translated

in dad’s shirts and ties.

It’s the past, when brother and sister

were all footsoles and eyes

together in a wood as steep as the Tyrol

that looms up unannounced, always a surprise.

Unrequited

He’d have called to say the sill is overrun

with moss, there’s moss on the light fixtures, moss

on his prepositions, when he bends and unfastens

himself from bed, he finds moss on his clothes,

a soft green runway of fuzz in the most

interesting section of his underwear.

I know what you need, the law’s wide dry hands

trying to bucket the truth: And nothing but

the small transparent sphere that breaks and fills

the moss’s thousand tiny throats. Let’s imagine

for a minute he has the soil, is really in it--

Levin moving through the rows with a scythe.

His feeling is metaphor so complete

it’s the hum alone on loan from the hive.

A Package Tour

It’s not untrue to say that Paní Barvíková was a great-grandmother

or she and three others were great-grandmothers

although they were unknown to one another

and to themselves as great-grandmothers.

Before those four, there were eight. Then sixteen,

and at thirty-two we could charter a bus (with room

for their trunks) and tour the Loire, chateaux already then antique.

It’s a costume drama of uncertain date; be not too dogmatic

in your visualization but do picture us

looking fabulous.

These being the days a woman’s body’s

respected absolutely in its tyrannical seasons

the better to be exploited absolutely.

I called them by their unpronounceable names:

Paní Vejvodová, Paní Frgalová.

Old tapestries of politeness swung substantially between us.

Even the legal rapes that bit them into keeping

secrets from themselves had hit them early enough at least

to yield fat little dividends.

From time to time

one of them would touch my hair or take my arm,

laying a gentle claim.

I saw one whispering into hands cupped

to a window; her words appear

as subtitles in the making-of documentary.

Even the wealthiest, most finely dressed, most widely read

in Romance languages shrank beside the poise of the French,

and so plus ça change.

They were my mothers, all,

but I was their guide,

I hoisted a furled umbrella.

I had my career, it’s important to me

to do some work of significance

or do my work conscientiously.

At night the Château de Chenonceau is lit with torches like a cake.

Aristocrats in period dress play their forefathers

in a hedge maze floodlit from below.

Puddles of rouge under the eyes

of also most of the men, perukes and heels impelling them to caper.

Some comic scenes when I mistake a few for great-grandmothers.

You know we’ve grown close because now

there’s something close to rivalry between us. Quietly in clusters

they agree their lives meant something regardless,

regardless of my arrival.

Why did you show us all these things?

What do you bring besides information?

Meanwhile I’d begun to sense, although this sense

was gradual and liable to withdrawing,

that I didn’t depend on them to feel entire.

I hated to leave them

I couldn’t refrain from saying

in their bad marriages.

And then I was here,

remembering the ovals of their faces

like blank money,

as if this could win me some advantage,

as if it might incline you to be generous.

Benvenuto Tisi’s Vestal Virgin Claudia Quinta Pulling a Boat with the Statue of Cybele

[a painting at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome]

A solid quarter

of it is blotted burnt umber

for the hull, a scripted curve, as if color

bricked over and over

could send a sailboat blowing from the canvas as matter.

Similar:

shipping the goddess from a backwater

then setting her up here.

And I’m the golden retriever.

Eyeballed from behind, female with yellow hair

contending with a hawser.

Manifestly unafraid to show my rear.

“Sip antiquity from my spot on the Tiber!”

Daylight buzzing like an amphitheater.

Not everyone is born to be a master.

He did sketch Michael roosting with his sword

on the grave of the Roman emperor

in perspectival miniature,

echo of the statue in the fore.

More on her later,

all the eunuchs and bees you can muster.

If you had to name the gesture

of the frontman with the beard

and frock of a Church Father

gaping at me from the future,

you could do worse than basta--hands perpendicular

to the ground, each white palm a semaphore,

head tilted halfway between concern

and something he won’t declare.

To all the girls Bernini loved before

I’d say, caveat emptor.

The deathless ars

longa, vita brevis guys will have me clutch a carved

toy boat but this provincial follower

of Raphael goes for the ocean liner.

Reality’s my kind of metaphor.

The heavens circulate with the times on the far

horizon and I don’t have anywhere

to be except this unambiguous shore.

Tumbril

You have to hope we

soon exhaust all hope because

you sense one final hope

and maybe the true one

can be hoped for only

after every hope has lost

its head.