Excerpt

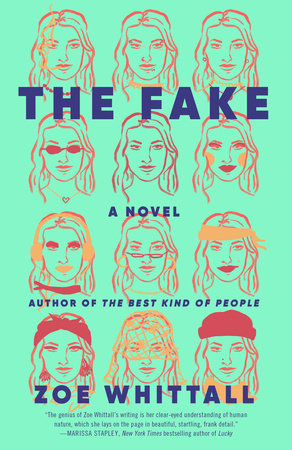

The Fake

TODAY

Shelby hides in the closet and calls her father. It’s a primal, childlike thing to do, to call your dad when you’re in danger. If you have a good father, anyway, and Shelby’s is one of the best. Also, she is maybe still a bit drunk, not thinking clearly. Voicemail. He’s the kind of dad who insists on singing his outgoing message to the tune of “Born in the U.S.A.”—

The Roberstons ARE not HOME! Soooo LEAVE A Message at the TONE!—with her mother’s voice in the background telling him to just stop it already.

“I think there’s someone in the house. I’m hiding in the closet. Can you come over?” Her heart sprints in place. The dog is no use in this situation. Coach Taylor Swift, a simple-minded but precious rescue pug, is now resting on a tattered quilt in the corner licking his asshole like nothing is wrong. Shelby pushes the mountain of dirty clothes in front of the closed closet door to block any sound. She rummages around on the stack of boxed shelves above the dog and finds a pair of Kate’s ice skates. She pulls off the purple plastic guard around the blades and shines her phone’s light on them so she doesn’t accidentally cut herself. This could be a weapon. She holds one skate by the ankle. If Kate were still alive, she’d have gotten up and grabbed the bat they kept under the bed and charged toward the kitchen turning on every light and singing the chorus to that annoying counting song from

Rent that somehow sounded menacing the way she sang it. Shelby always misses Kate but she especially misses her now, her butch bravado, except when it came to spiders or wet paper in the sink. Spiders are the femme’s domain, Kate said the day they moved in together, standing on a kitchen stool after seeing a daddy longlegs hanging out in the space between the fridge and the wall, ruling over a veritable city of baby spiders. Though Shelby is afraid of most things, she doesn’t mind spiders. She’d cupped and carried them to the window and set them free into the boxed herb garden as Kate improvised a thank-you song, still safely standing on the stool, fingers touching the ceiling.

Shelby texts her dad. The message goes green, which means he’s turned on airplane mode to sleep. Of course her father probably isn’t looking at his cellphone, he still uses it like a walkie-talkie. She tries the landline again. They don’t pick up. She remembers her parents have gone to the symphony. She’d gone to bed an hour ago, but other adults who aren’t dangerously depressed are still out having a good time right now. Should she call 911? What if it was no one? Everyone already thinks she’s going crazy. She scrolls through her contacts. Who are her friends? The ones close enough to call in moments like this? When you no longer have a partner, you have to rank your friends in order of most useful in an emergency. Her ICE listing was Kate. Whose phone was currently in a little Ziploc bag in their shared nightstand with her keys, receipts, and the contents of her pockets from the day she died. There’s Carol Jo, the person who lives closest, but Shelby had blocked and deleted her number the week before. So she texts Gibson.

This is going to sound crazy, but do you know where she is right now? Because I’m worried she’s in my house. She made some threats. He calls her back. She so recently considered him an enemy, someone not to be trusted, that it’s still odd to see his name pop up. She puts the phone to her ear and whispers, “I’m hiding in the closet.”

“Look, until today I would have said you’re overreacting, that she was only a harm to herself, but I honestly don’t know what she’s capable of anymore. Stay where you are. I’m coming over.”

Shelby hangs up. It’s very quiet in the house for five agonizing minutes, so quiet she contemplates just going out to see what’s really going on. She has a brief flickering euphoric feeling of

If I die, I die! Like she does whenever there is in-flight turbulence, or when a taxi driver speeds like a madman through the city and she’s too nonconfrontational to say anything. It’s a light feeling in her chest, a release of the illusion of control over her circumstances. Then Coach Taylor whines a little. She has to stay alive for Coach, a dog with such a complicated daily system of medications and nurturance needed just to be baseline okay. Maybe it’s just a raccoon in the garbage—this is Toronto, after all—or a vicious wind in the yard. Perhaps an ordinary robber who is strong-arming her flatscreen and going on his way. She reaches over to scratch Coach’s head, which makes them both feel sleepy. Maybe she should just go back to bed. She is lolling into what her therapist calls sensory underwhelm when she hears the sound of gunshots and breaking glass.