Excerpt

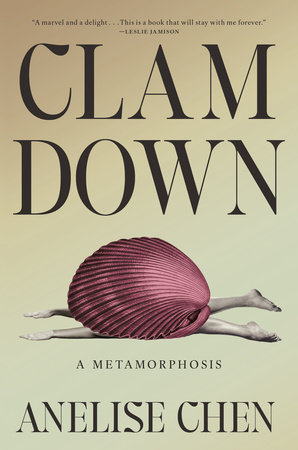

Clam Down

She hadn’t meant to become a bivalve mollusk, but it happened. Several nights ago, after a rib-bruising bike crash caused by momentary inattentiveness and conditions of reduced visibility (sobbing while cycling), the mollusk had briefly succumbed to an episode of hysteria, during which her mother kept texting her to “clam down.”

Clam down, she had commanded in that sober, no-nonsense way. At first, the clam looked all around her, like,

Who, me? Until she realized that her mother was addressing

her.

It made sense. Ever since the dissolution of her marriage, she

had been consuming a lot of calcium carbonate. This was what clams and other shell-building animals used to make their shells. These days, she kept rolls of Tums in her bag, which got whittled down throughout the day with alarming speed. On her desk, beside her usual writing implements—pen, notepad—was a flip-top container that was more fun to feed from. It rattled percussively when she shook the tabs out into her palm. They were the tropical variety, in delicate pastel colors: flavors that felt like a getaway. Like all getaways, the balm was instant but brief, hence the need for repeated doses. Humans were not supposed to ingest more than six per day, but clams could eat them as needed. Both species possessed a stomach, and hers hurt most of the time.

Looking back, it hadn’t been the first time her mother had issued that particular command. All summer, no matter what the mollusk had tried to convey, the response was much the same.

Clam down! Had there been a recent, lengthy conversation about seafood? Or perhaps the typo was made fresh each time, her mother’s subconscious pinning the bivalve as ideogram for conduct during crisis. Indeed: The word

fire in Chinese looked like a flame; the word

water like a running stream; the word

peace depicted a woman safe at home (notably a character in both daughters’ names). Perhaps the word

clam in English looked calm to her.

Everyone knows it’s useless to tell an upset person to “calm down,” but “clam down” was always a hoot. The first few times it happened, the clam (for now she was a clam) laughed and sent a screenshot to her sister, who was equally tickled. “She writes that to me all the time too!” They hahahahahaha’d into their text threads. Together, they recalled the document they once discovered on a shared Google Drive that turned out to be their mother’s journal. This journal had read more like a captain’s log than a confessional text, as it betrayed nothing about how their mother felt. Which was uncanny because this was a journal she kept during some of the family’s most tumultuous years. In lieu of emotion, the journal was full of exhortatory language, with which she compelled herself to think positive, lose weight, and stay

claaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaammm(Either their mother had fallen asleep while typing that sentence, or it was meant as a stage direction: read while screaming.)

Oh, their mother’s clam smile. That tight, insistent grimace that stretched from jowl to jowl. With it, she could smile her way out of anything.

Admittedly, the girls didn’t know much about clams. Their early exposure to sea life had been restricted to the seafood section at the 99 Ranch Market, a kind of poor kid’s aquarium. Upon being released from the car, they would rush over to the heaped bins to gently torment the sea creatures. They tapped on their shells with metal utensils until the animals snapped shut and shot out spurts of murky brine. Whether condemned to the seafloor or as food items to be poked and prodded by children, these creatures still had recourse against pain. If you shut yourself tight enough, nothing would happen to you.

A cursory Google search revealed that most people want to know whether clams are alive, or happy. Now the clam was at the library at the university where she worked, surrounded by books. No longer in denial about her true species, she was here to learn more about her evolutionary history.

She was reading from a book called

Animals Without Backbones. Its cover featured a cartoon drawing of a squishy, undeniably phallic shape with googly eyes, amoebic and alert.

Clams belonged to the phylum Mollusca, which derives from the Latin

mollis or “soft-bodied,” the book explained. The molluscan body plan generally consists of a strong, muscular “foot” and a layer of tissue called the mantle that protects the viscera in the main body. Some mollusks, like clams, limpets, and snails, build protective shells out of calcium, while other mollusks, such as octopi, squid, and slugs, evolved to lose them. The shell-less mollusks, it should be said, are the intelligent species of the phylum, while she, a clam, “neither flees nor turns on its attacker but lies quiet and defenseless within its hard shell until this is split open, with a rock, to expose the soft, flabby, deliciously edible, bite-sized invertebrate within.”

She flipped the page.

Despite being helpless and delicious, clams have nevertheless managed to persist through time, thanks to their simple, ingenious technology. What clams lack in intelligence they make up for in endurance. Clams are “particularly hardy” creatures, appearing in the fossil records as early as the Cambrian period some 510 million years ago. Which means that clams had survived the extinctions of other, superior creatures, such as dinosaurs and mastodons. Some clams are so tough they manage to dwell 17,400 feet down on the dark seafloor, enduring hydrostatic pressure of almost four tons to the square inch. And down there, they live on and on. The oldest living animal ever discovered was a deep-sea quahog named Ming the Mollusk, who was 507 years old when he was dredged up from the ocean floor.

As the clam read on, she began to feel cozy, validated. Perhaps it was the coffee, or the sun slanting in through dusty windows. These facts were doing a lot to legitimize her methods. By clamming down, her species had actually done quite well for itself. Hadn’t this clamming down method worked well enough in her marriage? Instead of opening her mouth to spew seawater or sand, she swallowed whatever was bothering her and worried it under her tongue until it gleamed. She would coat the small agitation until it became round and pink and polished. Alone, she might examine the object, evidence of a job well done.

Look what I’ve made! Look what I’m capable of! In this way, she could look at the problem without any lingering feelings. After all, she was an artist; she made beautiful things, and this was how she felt strong.