Excerpt

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove

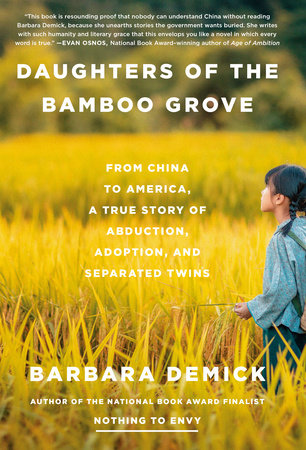

Chapter OneBorn in the BambooSeptember 9, 2000—From above, the landscape was a patchwork of florid greens and yellows climbing up and down a dizzying staircase. Chinese farmers hacked these terraced fields out of the mountains more than two thousand years ago with the ingenuity and persistence to shape the earth to their will. A single rutted road wound around the terraces, now flooded for growing rice, vanishing into the low-hanging mist before emerging at the entrance of a small village.

In a house at the edge of the rice paddies, a twenty-eight-year-old woman was trimming vegetables for lunch when she was interrupted by a familiar sensation. It was like a belt cinching around her middle. Zanhua wasn’t alarmed. Although she wasn’t sure exactly how far along she was, the ballooning size of her belly told her the baby was coming any day now. She was eager to give birth sooner rather than later, because the hundred-degree temperatures of an unusually hot summer left her overripe body drenched in sweat. Even as another contraction gripped her body, she smiled through the grimace. It was about noon, time for lunch, but she had other priorities. She carefully set down her kitchen utensils and covered the bowl of rice with a plate to protect it from the circling flies. The first flush of autumn had yet to settle upon the rice paddies of Hunan. She wiped her brow and washed her hands, even tidied up a bit. Then she called out to her mother in the next room that they should get ready.

Zanhua moved quickly but deliberately. She wasn’t agitated. This would be her third time around. She was hardly bigger than a child herself, standing well under five feet, narrow in the hips, at least when she wasn’t pregnant, but she was confident in her physical prowess. Since early childhood, she’d helped out in the family fields, which left her arms and back taut with muscle. She had a broad, flat nose and a ruddy complexion from working outside, although this summer she was paler than usual, since she’d mostly stayed indoors, not wanting to advertise her condition. She’d taken care to buy extra-large clothing to conceal her swollen body. She was anxious, not about childbirth itself—she wasn’t the type to complain about pain—but about the need for secrecy.

Since 1979, China had limited most families to only one child. Under the law, you were supposed to apply for a permit even before you got pregnant. It was the signature policy of the ruling Communist Party, which had developed an almost mystical belief that population control was the secret to jump-starting the economy. The law was enforced by an agency euphemistically known as the jisheng ban, literally “planned birth” or “family planning agency.” It didn’t actually plan or advise so much as punish. Violators could be fined more than a year’s wages, their homes demolished and property confiscated. If you were visibly pregnant without a permit, you could be hog-tied and hauled away for a forced abortion. Then they’d send you a bill for the favor. No matter that the village where Zanhua grew up in Hunan Province was deep in the mountains, almost an hour’s drive from the nearest government offices or a two-hour walk when mountain roads were washed out; the law was never far away. The village was full of spies and Communist Party loyalists who might rat you out.

The Communist Party ruled here with impunity. Hunan Province is in more ways than one the heartland of modern China. With a population as large as that of France, Hunan is a landlocked province smack in the middle of the country, just below the Yangtze River. The founder of modern China, Mao Zedong, was a Hunan man, born about one hundred miles away from Zanhua’s village, in Shaoshan—roughly the same neighborhood, although not nearly as mountainous nor as poor. Mao was the son of what the Chinese called a “prosperous peasant.” He was educated in the Hunan provincial capital of Changsha, where he read the classics and organized one of the first branches of the Socialist Youth League. In 1927, he led a few hundred peasants to become guerrilla fighters in the Jinggang Mountains, which, bordering Hunan and Jiangxi provinces, would become known as the cradle of the revolution.

Mao was inspired by the plight of Hunan’s peasantry and the need for land reform. Hunan is the largest rice-producing province in China, its semitropical climate just warm enough, the rainfall generous, and the soil red and fertile. It should have been a place of abundance. But rice farming was a precarious existence. Rice farmers survived at the mercy of floods, droughts, and unscrupulous landowners, who often demanded most of the crop in rent. When he founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mao vowed to redistribute the land and liberate the underclasses from the tyranny of the ruling class.

Instead, it got worse. Farmers were forced into inefficient communes that were required to sell most of their grain at below-market prices for export abroad. Farm equipment and kitchen utensils were melted down in backyard furnaces to create steel. This was all part of an ill-conceived vision to turn China into an industrial powerhouse that would rival the United States and the Soviet Union. But the furnaces produced pig iron of such poor quality that it was of little use. Meanwhile, fueling the furnaces led to widespread deforestation. The diversion of the workforce away from agriculture resulted in a famine. An estimated forty-five million people died during what was known as the Great Leap Forward. It was followed by another man-made disaster—the decade-long Cultural Revolution, in which the intelligentsia or anybody perceived as elite were eradicated in the name of class justice. Neighbors were goaded into persecuting one another. The madness endured until Mao died in 1976. His successors wasted little time in rolling back the worst of his excesses.

At the time of Zanhua’s birth in 1973, China already was on the cusp of reinventing itself. Although Mao’s portrait remained on everybody’s walls, the country had started to wriggle free of the strictures of doctrinaire communism. In Zanhua’s village, farmers took it upon themselves to dismantle the communes even before the land was legally distributed to households. Although they didn’t own the land outright, they earned the right to farm their plots individually. Productivity soared. Zanhua was told she should be grateful for the food of the land—the rice, sweet potatoes, and cabbages grown on her family’s fields. Unlike her parents, she didn’t have to survive on wild grass, roots, and bark. Her father had a job at a state-owned factory that made dishware. It was an hour’s walk away and paid a tiny salary, but there were perks, like an occasional bundle of pork or a chicken. She wasn’t starving, but she was still hungry.

The village, then called Shanghuang, literally “on the yellow,” was poor even by the standards of one of the poorest countries in the world. It was so wild that until the 1960s tigers were still seen in the nearby mountains. The steep terrain dictated that the terraced fields be small and irregularly shaped, with little of the postcard-perfect symmetry that attracted photographers to the undulating green terraces elsewhere in China. The houses were built mostly of wood, weathered and flimsy, brick still outside the reach of many villagers. The roads were poor to nonexistent.

Zanhua occupied an unfortunate position in her family’s birth order. As the fourth of six children and the third daughter, she wore her older siblings’ hand-me-down clothing, so threadbare it was beyond patching. When her parents went to the township on market days, held every five days, she begged her mother to buy her clothing of her own.

“Only if you work harder” was the retort.

That was impossible because she already worked all the time. As a small child, her work began at dawn, when she tended to the oxen. She weeded the fields and washed laundry, an ordeal without running water or soap. It required multiple trips to the well, since she was too small to carry more than one bucket of water at a time. She cared for her younger siblings, hand-washing diapers made of old clothing. From the time she was seven, she prepared her own meals, since her parents and older siblings were busy with their own work.

Her village had an elementary school housed in four ramshackle wooden buildings, one for each grade. An empty lot served as the playground. The school offered basic instruction in math, Chinese, physical education, and, most important, music. The kids couldn’t read well, but they were indoctrinated through song.

Without the Communist Party, there will be no new China.The Communist Party toiled for the nation.The Communist Party of one mind saved China.It pointed to the road of liberation for the people.It led China toward the light.Zanhua attended the school but rarely finished her chores quickly enough to get there by the start of the school day. She also had in tow one of her baby brothers. There was nobody else to take care of him. The teachers were sympathetic. Most people in the village were relatives, so they understood her predicament. Nonetheless, the toddler fussed so much that the school eventually asked Zanhua to leave. As a result, she dropped out after three years and barely learned to read.

Later in life, when asked what were her happiest memories from childhood, she said that she had none.