Excerpt

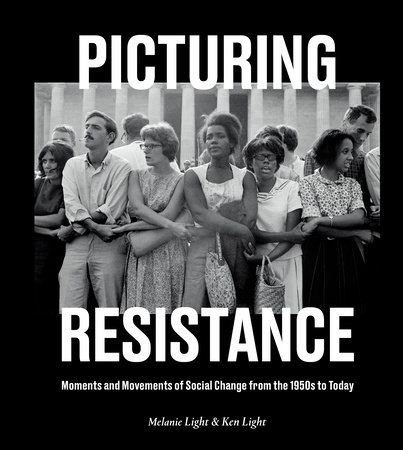

Picturing Resistance

Introduction Resistance is the lifeblood of America. Protesters—chanting in crowds of fifty thousand or hundreds of thousands for justice, freedom, or redress—know this. When individuals gather for the higher good of our national community, there is a feeling of being deeply alive and deeply connected across all divides. When hundreds of Black and white people link arms for the first time in public, or you look out over a sea of pink pussy hats, the possibility that all people can live in peace and tolerance becomes real, if only for a moment.

America has boldly declared that government should serve its people, that all are created equal, and that people have inalienable rights, among them being “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” These words are enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, which declared independence not only from England but also from the destructive characteristics of human nature that foster tyranny, fear, prejudice, and oppression. Those words emerged after years of protest and resistance during colonial times.

This credo is not a set of operating instructions, though. It offers guideposts for the work of citizenship. Indeed, we have considerably broadened the interpretation since the 1776 drafting. The Founding Fathers principally had themselves in mind: powerful, white, landowning men. Some owned slaves. White men without land could not vote. Their wives had no rights at all, and they thought nothing of taking the indigenous people’s land for their new country’s benefit.

It was clear, even then, that there was much work to do to create “a more perfect union.” Right after the Declaration was signed, British abolitionist Thomas Day wrote “If there be an object truly ridiculous in nature, it is an American patriot, signing resolutions of independency with the one hand, and with the other brandishing a whip over his affrighted slaves.”

This desire to fully realize the American experience is at the root of the resistance and protest movements that have shaped, moved, and stunned the world. For over two centuries, millions of women, poor people, immigrants, African Americans, Native Americans, and nonwhite people living in America have devoted their lives to ensuring the full range of liberties guaranteed in that precious founding document. They’ve marched and chanted; they’ve testified and organized. They’ve held sit-ins, led boycotts, gone underground, and leveraged technologies to their advantage. They’ve risked their lives and been beaten, harassed, imprisoned, and killed. Some lived to see their efforts bear fruit. Many did not.

Every social justice struggle takes much longer than expected to effect positive change. Social norms must catch up with the visionaries; the organic nature of grassroots organizing and the leadership must be effective over time. That righteous rage against the desecration of truths you have learned must give you the courage and solidarity to fight for your rights over the course of time. If a country’s consciousness is ready, you can get a law passed. A law gives you a tiny ledge on which to build ideas into mainstream acceptance and practice. To get there, many people must stand up and speak out persistently, often at significant personal cost, to chip away at the barriers to equality: prejudice, denial, and hatred. It can take generations. This is what Dr. King meant when he said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

The collective bond created by surviving the tribulations of resistance is what motivates activists and protestors to keep taking risks. Civil rights activist Bob Moses describes being jailed with twelve others in subhuman conditions during the Freedom Rides to register voters in the South: “Later, Hollis [Watkins] will lead out with a clear tenor into a freedom song. [Robert] Talbert and [Ike] Lewis will supply jokes, and [Chuck] McDew will discourse on the history of the black man and the Jew.” And these true believer communities operate on trust. The hundreds of thousands of protesters who flocked to Washington, DC, to protest the Vietnam War over the years arrived with no place to stay, and local protesters and fellow travelers took them in. The power of a movement is a kind of magic that people remember for the rest of their lives. Grandparents have saved their buttons and posters; if persuaded to bring them out, they will tell of some of the most cherished moments in their lives.

A movement unleashes creativity and ingenuity. Over the years, the means of calling people together to fight for justice has changed. The civil rights movement started with plain signage; as it branched out into the Free Speech, feminist, anti-war, and other corollary movements, protest materials exploded with color and design. Street theater used delightful props and costumes. We’ve gone from broadsides, to mimeographed handouts, to Instagram. The actions are innovative and powerful, always springing from the primal call to unite for a higher purpose.

This book celebrates the path of resisters in America in the modern era. It begins with the Supreme Court case

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and the civil rights movement that followed, setting the tone and inspiring the decades of activism to come. The tumultuous sixties gave way to the seventies, the backlash of the eighties and early nineties, and the digital revolution and rapid globalization of the twenty-first century. Each photograph tells a story. Some are iconic images taken at watershed events in big movements; others illustrate smaller but no less important moments.

The images show every phase of resistance, suggesting a paradox: consistent and disciplined organizing coupled with the emotional outburst of people moved to their core. The marches, actions, and movements depicted in these images stem from years of work by people with clear, unstoppable vision. And at every protest, march, or vigil, the visual journalists and independent photographers are there. Photographers bring the voice of the people to the insulated offices of government and persuade calcified communities to shed their outmoded ways of thinking. The long hard work of social change agents is nothing without the visual record. If a protest is not recorded or shared, it cannot be effective, falling prone to being forgotten or suppressed.

The mother of modern social movement photography is Dorothea Lange. She left her comfortable portrait studio in San Francisco to document people’s suffering during the Great Depression. Her work endures as one of the most effective campaigns ever to persuade an insensitive Congress to legislate aid to those suffering.

Digital photography, smartphones, and social media have changed how events are documented. Photographs look and feel very different across the decades. Before the internet, photographers would create whole stories for the cultural gatekeepers of underground newspapers, newsletters, and posters. Some images made it into mainstream media, too. Though from a limited point of view, the upside of that era is that there are historical repositories of images.

Today, photographers want a single shot that can be quickly loaded onto a digital platform to grab attention. Formal composition considerations and the idea of a narrative comprising a collection of images often fall by the wayside. Once shared, an image can be lost or forgotten among a million others. The message might be more about the photographer’s experience at an event: “I was there” rather than “Protesters want this change.” With so many more people on the scene, all sharing billions of photographs across a vast platform, it can be difficult to find usable images of recent activism.

Even so, photojournalists, documentarians, and independent photographers of social movements have built a record of the people’s voice over time, which illustrates a measure of our progress. The early good work of LGBTQ+ and AIDS activists created more inclusion and acceptance, yet the existence of the Black Lives Matter movement today is an embarrassing indicator that we have not yet done the deeper work to understand and remedy our cultural racism. Celebrate with us that dance, both glorious and fierce, between politicians and people—both conservatives and progressives—that moves our society toward a higher consciousness. The images here work to unite people across the decades, so resisters today can viscerally grasp the historic value of their efforts, inspired by each other’s vision of a safe, just, and prosperous life, country, and world.

We hope you find your place among these stories. Those who march, demonstrate, and agitate in the twenty-first century are part of a long legacy of uprising and resistance.

It is in our blood.

—Melanie Light