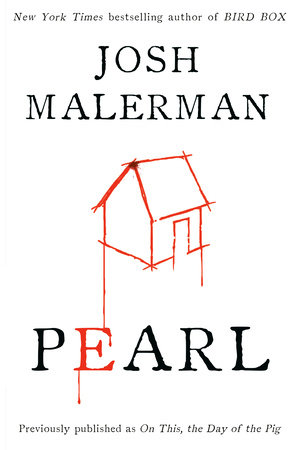

Excerpt

Pearl

Up Murdock, away from downtown Chowder, passing the wheat fields and the forest east of the road, tall pines that unfolded like a long, complex bedspread, separating Chowder from Goblin and the other less agricultural areas of mid-Michigan, they pulled onto Grandpa’s gravel drive just before noon. Sherry eyed Jeff briefly, checking to see if maybe he’d had a change of heart. If maybe he was smiling like he used to. Grandpa’s world was a fun world if you let it be. The farm. Where Jeff and Aaron used to ride the horses and chase chickens and oink at the pigs. Where the brothers spent nights outside, sometimes without a tent, sometimes just on their backs on the grassy slope that led from the farmhouse to the barn. This place was childhood. This place was supposed to be special. The farm

meant something.

“Doesn’t it?”

Sherry hadn’t meant to say that out loud.

“Doesn’t what?” Aaron asked. But Sherry didn’t answer. And Jeff stared at her like he might’ve known what she was thinking.

Sherry parked the wagon by the front porch steps. She looked up to see Grandpa standing behind the screen door. He waved.

“Hey, Dad,” Mom called from behind the rolled-up window.

Grandpa waved again, as if maybe he’d forgotten he’d already done so.

His thin white hair stirred with an easy autumn breeze. Sherry wondered what was on his mind, what clutter of his own.

She and the boys got out of the car.

“Hello, Sherry,” Grandpa said. “Hello, boys.” He looked tired. Sherry always said Grandpa was toughened by farm life. Jeff used to believe that.

Sherry hugged him at the door.

“Thought I’d put them to work today,” Grandpa said, nodding to the boys.

“That sounds good,” Mom said. “They could use it.” And it would give her a chance to grovel in private.

It had been a hard summer.

Stuff it in the mind-bag.Yes. The mind-bag. The secret, unseen place where Sherry stuffed all her dark thoughts, her absurd worries, the unprovoked hunches she’d felt most her life, the premonitions of Pearl.

Grandpa squinted down at his grandsons.

“I was hoping Aaron could collect some eggs for me. And Jeff . . . maybe Jeff would like to feed the . . .”

Jeff held his breath.

Don’t say feed the pigs, Grandpa. Don’t say Pearl.And why not?

“. . . horses,” Grandpa finished.

Sherry smiled, but her own private stresses were drawn firmly on her face. Often she imagined the mind-bag hanging on a curled finger in an otherwise lightless room. A place only she could find it, hidden from the prying eyes of Chowder, Michigan, and the whole wide world beyond. But recently that bag had been relocated to her hip, a place anybody could see, if they cared to look. Yes, Sherry Kopple had started wearing her emotions on her sleeve, a look she didn’t quite love. Her recent anxiety stuck out like the stump of a third foot and was about as useful to boot.

“How’s that sound, boys?” Grandpa asked. “Good enough?”

The brothers nodded. Yes. Eggs and horses. Safe areas on the farm.

Grandpa walked them into the farmhouse, through the kitchen, to the back door.

Aaron followed Mom outside, a foot from the cellar door in the grass, but Jeff paused at the screen, looking down the slope to where the evergreens hid the pigpen.

“The horses can’t come to you,” Grandpa said. And when Jeff looked up, he saw all three of them were waiting.

Aaron laughed at him as he exited the farmhouse.

Grandpa led him to the stables, and on the way, Jeff heard them breathing behind the trees.

The pigs.

The sound remained lodged in his mind, in his bones, as he passed them, loud, louder than the horses were, even when he stood inches from the muzzle of a mare.

“This here’s their favorite,” Grandpa said, fishing a handful of damp, yellowing oats from a brown wooden trough. “But you gotta be a bit careful ’cause they’ll chew your fingers clean off.”

Jeff looked up and saw Grandpa smiling, sadly, behind a show of white whiskers. His eyebrows had always remained dark as midnight, though.

“Really?” Jeff asked.

“No,” Grandpa said. “Not really. But it was fun to see the look on your face.”

It felt good. Falling for a joke.

Through the open door, Jeff saw Aaron eyeing the chicken coop, readying himself to pick some eggs.

“Enjoy,” Grandpa said. “But don’t eat more than the horses.”

Another joke. Good. Felt good.

Then Grandpa left him alone in the stables. Jeff looked up, into the eyes of the brown horse he stood by.

“Hello,” he said. “You hungry?”

It felt good to talk. Felt good to pet the horse’s nose. To feel the strong neck and shoulders.

“You remember me, right?” Jeff smiled at the horse. Wished it could smile back. “My name is—”

Jeff . . .Jeff stepped quickly from the animal. The black emotional chasm that came with the sound of his name was wider, darker, deeper than any nightmare he’d known before. As if, in that moment, his ill-defined apprehensions about the farm had been galvanized, and everything Jeff was afraid of was true.

He dropped a handful of grains and stepped farther from the mare. Wide-eyed, he stared at her, waiting to hear it again, waiting to hear his name spoken here in the stables.

But the horse hadn’t said his name.

“Mom?” he called, looking to the stable door.

Come, Jeff.Jeff backed up to the stable wall.

“Aaron? Are you screwing with me?”

It could have been Aaron. It

should have been Aaron.

But Jeff knew it wasn’t.

He folded his arms across his chest, combating a cold wind that passed through the stable.

Come to me, Jeff . . .It sounded like the voice was traveling on the wind. Or like it

was the wind. It was made of something his own voice didn’t have. He didn’t want to say what it really sounded like. Didn’t want to say it sounded like the voice was coming from outside the stables, up the hill, from the pigpen behind the trees.

Jeff exited the stables, stood outside under the sun. Aaron was out of sight. Mom was probably in the farmhouse, talking to Grandpa.

It wasn’t pretty, watching Mom beg for money.

Jeff . . .It was coming from the evergreens. Jeff knew this now, could hear this now, and he wouldn’t have been shocked to see a farmhand peeking out between the branches using his pointer finger to beckon him closer.

Jeff . . . come here . . .Without deciding to do it, Jeff took the dirt path to the trees. He crouched on one knee and split the branches. Through them, he saw the pigpen and the pigs lazing in the mud.

Jeff stood up.

He didn’t want to get any closer. Didn’t want to be alone out here at all.

He ran up the grassy hill to the farmhouse.

JEFFLouder now. Strong enough to root Jeff to the ground.

He looked over his shoulder back to the hidden pigpen.

Come, Jeff. Sing for me . . .Cautiously, Jeff walked back down the hill, to the end of the row of evergreens.

Most the pigs were gathered together at the far side of the fence. One paced the length of the pen, bobbing his head, snorting, half covered in mud. It looked to Jeff as if he was thinking.

Jeff looked back to the chicken coop. No Aaron. Still.

When he turned back to the pen, Pearl was all he could see.

Pearl.Sitting on his ass like a person might, his front hooves limp at the sides of his belly, his head was cocked slightly to the side, his pink ears straight, high above his head. His bad eye looked dark, hidden, but his good one was fixed on Jeff.

In it, Jeff saw an intelligence that scared him.

He didn’t think a pig could “stare” the same way a man did. Yet Pearl

was tracking him, following his lead, as Jeff stepped slowly toward the pen.

By the time he reached the gate, Jeff was breathing too hard. Felt like he’d done a lot of work. Felt like he’d unloaded a truckload of hay. Felt weak and skinny and cold and exposed and . . .

Dumb, Jeff thought.

Like he’s smarter than you.Yes,

dumb. That was the worst of it. And Pearl, it seemed, knew it.

A half smile appeared under the pig’s snout, or maybe it was just the way his lips naturally curled up at their ends.

The pacing pig pissed, and it sounded like a hose shot at the mud.

“Hello, Pearl,” Jeff said. He felt like he had to. Like it would have been insane not to—like he would have been admitting something too dark if he was too afraid to say hello to a pig.

The other pigs seemed roused by Jeff’s voice. They shuffled in the mud, sat up. One lifted his head to get a better look.

Jeff fingered the latch. Pearl watched him.

Staring.

Assessing.

Planning?