Excerpt

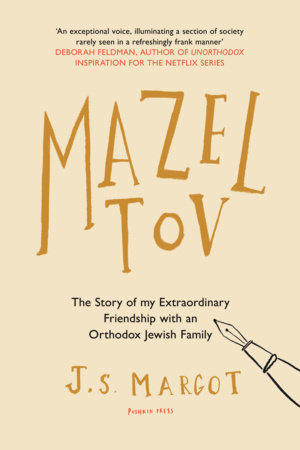

Mazel Tov

One

It must have been the beginning of the month. The new academic

year hadn’t yet begun and I was heading for the canteen,

feeling relieved, having just resat the Spanish grammar exam. To

get there, I had to walk through the hall of the university building,

past benches where dozens of students sat chatting and smoking.

The route to the canteen was more exciting than most lectures.

Noticeboards lined the walls, full of intriguing announcements:

“Who wants to swap my landlord for theirs?”, “Feel like coming to

Barcelona with us? Room for one more person. Conditions apply.

Call me” and “Free sleeping bag for anyone who’ll join me in it.”

A single corner was reserved for the university’s job agency.

If one of the jobs displayed in a lockable, plastic showcase looked

interesting, you’d note down the number of the vacancy and go to

the little social services office a bit farther along. There a lady with

a long-suffering expression would tell you the details, which usually

boiled down to her giving you the name, address and telephone

number of the employer. Then, sighing under the weight of her

boring job, she’d wish you good luck with your application.

The agency had provided me with a lot of temporary jobs in the

previous two years, from chambermaiding to dishing out detergent

samples, from headhunter’s assistant to museum attendant.

When I came across a handwritten job vacancy: “Student (M/F)

required to tutor four children (aged between eight and sixteen)

every day after school and coach them with their homework”, I

immediately wrote the number on my palm. An hour later the

lady from the job agency gave me the contact details of the family

in question. I will call them the Schneiders, which is not their real

name, though their name also sounded German, or German-ish.

The Schneiders, the lady said, were Jewish, but that shouldn’t be

a problem, and if it was a problem, I could always come back and

she’d try to see if we could work something out, but she couldn’t

guarantee anything, because you never knew with people like

that—which she apparently did know, just as she knew that the

Schneiders would pay me 60 Belgian francs an hour, which wasn’t

a lot, but could have been worse. When it came to money, she

informed me, Jews were a bit like the Dutch.

When I stared at her in surprise, she seemed taken aback by my

ignorance. “Why do you think so many Dutch people come here

to study interpreting? Because it’s a good course and it’s cheap.

As soon as they’ve got their diploma, they whizz off back to their

country. So we’re basically training our biggest competitors. Luckily

the university gets a subsidy for foreign students, so it’s not all bad.

What I want to say is: don’t let yourself get pushed around. Don’t

accept an unpaid trial period. Even if you decide to stop after the

first week, they have to pay you for the hours you’ve worked.” I did

quick sums in my head as she babbled on, calculating that I could

earn 600 Belgian francs a week: 2,500 a month. Back then, when the

rent of a small flat was about 6,000 francs a month, it all added up.