Excerpt

We Loved to Run

Warm-UpWe hated a lot of things. A gradual hill in the second mile of a cross country race. Two hard workouts in a row. The little packets of Lorna Doones in our brown-bag lunches that Assistant Coach picked up from the college cafeteria: like vanilla chalk. Big toenails that were a tad too long. When our coach said,

Here’s where you make your move. Inner-thigh friction. Holes in our socks. Our mothers’

Shouldn’t you take off one day a week?We hated our coaches. We hated them for encouraging us to have a love-hate relationship with our bodies, for telling us on some days that we were strong, and on others that we were fat. Only they didn’t say it that way. They said,

You’ve lost your lean, which meant a gain of a pound or two, a half-percentage point of body fat. As punishment, we had to be the rabbit. We had to run as though something dangerous were chasing us. Though we hated being told what to do, we loved it, too, our emotions sometimes not much more evolved than those of sulky thirteen-year-old girls who not-so-secretly longed to be loved the best in the whole wide world, who couldn’t take one bit of criticism without totally losing it.

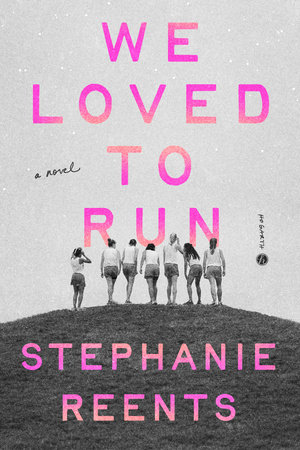

There were six of us. Two seniors: Danielle and Harriet. Three juniors: Liv, Chloe, and Kristin. And Patricia, an exceptionally talented sophomore who wanted to transfer. You’d find more runners in the 1992 Stanzas (the stupid name of our yearbook). But we were the core, the top six, not that you could tell from studying the photo. We looked just like everyone else—healthy and young—but we were the fast ones, even if this was invisible.

We hated our coaches but we also loved them, especially Coach, with his British accent by way of Uganda. He wore a heavy gold watch and made tracksuits look elegant. Who knows how he ended up at Frost, a tiny college in a tiny corner of New England. We loved Coach for loading us on a van and ferrying us to the running shop in a neighboring town to pick out shoes. We never knew when it was going to happen, which made it even better. Kristin and Patricia were always giddy with excitement because when they’d decided to come to Frost, they both thought they’d sacrificed the freebies that the Div 1 coaches had dangled in front of them. But it turned out that Coach had a slush fund from a generous alum, and he could buy us new shoes once a season. He played songs by a German band, Trio, whose most famous song “Da Da Da” was unknown to us but quickly became our favorite, the anthem of our parties: “I don’t know you, you don’t know me.”

We hated running, and we loved it. We spent so much time trying not to think about our bodies that we were always thinking about them. Thinking about how they were not hungry or not injured or not fatter or weaker than the body of some other girl. Running was the glue that kept us together, but it was also a truth serum, drawing out feelings we’d rather not have. Danielle secretly envied Kristin for being so effortlessly beautiful: Princess Di in denim. You weren’t supposed to be fast with boobs as big as hers. Kristin was in awe of Harriet’s self-control, the fact she’d never eaten a cafeteria dessert, not once in three years. Liv wished she could speak her mind as effortlessly as Danielle did. Harriet wanted to trade places with Patricia, not forever, but maybe for a couple of months, just to see what it was like to be from rural New Mexico. Patricia didn’t want anything the girls on her team had, except for maybe Kristin’s black cowboy boots and Harriet’s nose ring, but her parents would lose it if she came home with a pierced nose. She was mostly happy with the way she was, even though a lot of things at Frost told her she shouldn’t be.

Chloe and Kristin were always hammering on easy days. Patricia took the intervals out too fast. The pack could have let her go but never did. We took the bait. There was no shame in running as hard as you could and then puking. There was no shame in grunting, spitting, farting, leaving skids of snot along your arms. Danielle cried after New England Div 3 Championships, a year earlier, but there was no shame in that, or at least not too much. We’d run our hardest, but it wasn’t enough to carry us to Nationals. Emotions did not behave predictably under physical duress. We loved each other, too, the love as dark and sticky and intense as blackstrap molasses. We’d stand at bathroom doors, sentries, turn on the taps full-tilt, sweep the hair off each other’s foreheads, stroke each other’s backs while a stomach clenched and released. Danielle regularly threw up after she drank too much, sometimes preemptively. It was an effective way to head off a hangover. We shared tampons, the treats our moms sent us, clean socks, joy and shame and deodorant. We were friends like that.

We loved running because we loved repetition (breathe, stride, breathe, stride, breathe, stride), getting lost in thought, the endorphins that flooded our brains after several miles and swept away obsession and weariness, all that seemed dire and tragic in our college lives, and narrowed our focus to covering each kilometer of the 5K cross country race as swiftly as possible. We loved it because it was who we were, who we’d been in high school, who we hoped to be in futures we couldn’t yet imagine. Strong and fast. Fast and strong.

We loved winning, but we didn’t always love what was required: cross training, pool workouts, the flotation belts that we wore while running in place in the deep end, serious stretching, form drills, walking backward uphill, cool-downs that were more than five minutes and warm-ups that were more than ten. Chloe really hated lifting. Harriet did, too, though she put on a good show by doing high reps with almost no resistance. She wanted to like lifting because Professor Witt, an old-school feminist who taught WAGs, swore by weight training. Women could be just as strong as men, Witt claimed; they just needed to get over the social stigma of muscles. Whatever, we thought. Witt had never run a mile in her life.

We also hated rest days and easy laps between 400-meter repeats, not because we hated resting, but because it was never quite long enough to recover. Anticipating a workout was always worse than finishing one. Fartleks—which the men pronounced

fartlicks—could make us puke. (We growled when the men urged, “Go tits out, ladies!”) We hated that word

ladies more than we hated the word

tits. Tits could be thrilling in the right context. We hated running on rainy days until the moment we were drenched, sucking water from the end of a hank of hair. On hot days, sunscreen stung our eyes, but we could skinny-dip in Puffer’s Pond, and we did, especially if the men were doing a separate workout, and we expected an ambush. We liked the men’s team, though screwing them could feel like making out with your brother. It could be nicer than that, too. It depended on how you felt about someone else’s bruised toenails, bony hips, rock-hard thighs.

We loved to run, and we hated it. To run, you had to be willing to accompany yourself on long lonely journeys. You might know the time (90 minutes, two hours, 45) but not the route. Maybe you knew the route—through a shady residential neighborhood, through the park with a hill that looked like a camel’s hump, onto the trail just beyond the tennis courts, and then—up, up, up—the foothills opening in front of you like another world: the old military cemetery, the firing range, the corral where several weary horses shifted from hoof to hoof and ambled to the fence wondering whether you’d palm them an apple. Even if you knew where you were going and how long it usually took, you could never anticipate what you would see along the way. Back home in New Mexico, Patricia saw rattlesnakes in late May and early June when they were coming out of hibernation. They draped themselves across trails, seeking a sunny spot to warm their cold hearts, and Patricia hurdled right over them. Chloe saw a fox at the northern edge of Central Park that might have been just a skinny dog. Liv got lost in cornfields in southern Illinois, where her dad’s family was from. Danielle was chased and bitten by bats, not once, but twice over the course of two weeks just before sophomore year. She was running along the soupy Seekonk River in Providence. It was not a joking matter, even though there was something inherently absurd about being bitten twice in a three-week stretch and having to get all those rabies shots. Was she cursed? If you mentioned it, you were courting Danielle’s wrath.

We sank to our ankles in mud, we slipped in snow. We got heat stroke in the summer, mild frostbite in the winter, but those were just minor hazards. The real obstacle—underneath the sharp pain in a hip, the mechanical clicking of a knee, the weird way that teeth ached from huffing in winter air—the real obstacle, unchanging and always there, was the desire to stop, and the knowledge that we couldn’t. We could never stop because if we did, then we would know we could. If you stopped once, you might stop a second time. You might never run again.