Excerpt

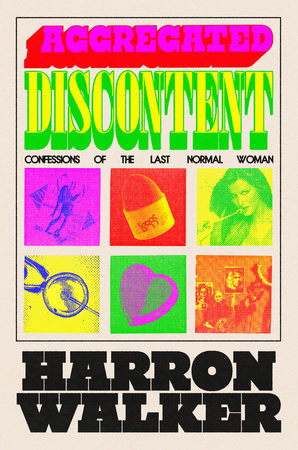

Aggregated Discontent

Obvious Community MemberIt’s not like I had the medical records of the other dozen or so people in the theater, which was about to screen Monica, the big trans movie of the summer. But as far as I could tell, my boyfriend, Mike, and I were the only actual trans people there to see it.

The lights were, of course, somewhat dimmed as we walked over to our seats, but on our way I didn’t spot any “obvious community members,” or OCMs, as my dear friend Lola likes to call them: those people who visually scream one or more letters of our clunky little acronym without having to actually say anything to make that affiliation known. Then again, Mike and I weren’t exactly giving OCM either—or maybe we were? I mean, that’s the thing about not being able to see yourself from an outside perspective: You can’t see yourself from an outside perspective. Maybe everyone else in that theater was also trans themselves, silently remarking, just as I had moments before, that they were the only trans people there.

Monica, a 2022 Venice Film Festival favorite that enjoyed a wider release the following year, concerns a trans woman returning home for the first time in years to reconnect with her family of origin. I mostly liked it, especially the scene that plays just before the credits roll, in which the title character, played by Trace Lysette, kneels down to give her sensitive, creative, artistic nephew a word of advice before he sings the national anthem in front of his whole school:

When you get on the stage, I want you to take a moment and think to yourself as you look at everybody, OK? And you say to yourself, “You lucky bastards, here I come,” all right? And you slay that stage, and you make a moment. You got everything inside you, all right? OK, go get ’em.

In case the reason for my use of terms like “sensitive,” “creative,” and “artistic” weren’t plainly apparent, Monica’s nephew is probably gay, maybe even trans like his aunt is. She sees it. Her brother, the boy’s father, sees it too—and, thankfully, doesn’t seem to have a problem with it, whatever “it” ends up being, unlike his mother when Monica began to deviate from the norm. With this in mind, the scene reads like Monica is telling her nephew something that she wishes someone could’ve told her when she was his age. Her words are ones of encouragement derived from the wisdom that she’d been forced to learn in the years she was on her own, delivered to the boy by the kind of maternal figure that she herself never quite had, at least not in the house she grew up in. Monica ran away from home in her teens and has only returned now, some two decades later, to make peace with the dying, dementia-plagued mother who drove her away in the first place. She fails to rekindle that bond by film’s end, but she does manage to forge an unexpected new one with her elementary school–age nephew. She sees herself in him and sticks around for his sake, as well as for her own, perhaps in an effort to heal her inner child while at the same time trying to shield him from getting hurt in quite the same way.

I cried during that final scene for all the obvious reasons: I’m an adult trans woman who’d been one of those “sensitive,” “creative,” “artistic” little boys herself, fighting the “faggot” allegations from the moment some bowl-cutted Prometheus in a Big Dog shirt introduced the word to the playground. As I watched the scene, something buried deep inside me, something long interred within that traumatized core whence all personal essay fodder springs eternal, burst open in yearning as it ached for a similarly healing exchange—and I’d never even been thrown out of the house! Nor lived through anything comparable to what Monica probably had to endure as a result of her mother’s rejection.

The scene, in some ways, redeemed Monica for one of the issues that I’d had with the film up until that point, which was that its protagonist seemed to live in a world in which no other trans people existed. Even beyond the bounds of her family’s stifling, hetero-suburban bubble, she didn’t seem to have any friends at all, trans or otherwise. She never calls any of them, never texts them in distress or even to complain in some overly long voice memo, as I’m wont to do to a few different group chats at least forty-nine times a day. In fact, her only confidante for most of the film is the voicemailbox of a shitty ex-boyfriend that she cries and screams into whenever she gets upset. She seems extremely isolated, which, I get it—that’s the point: Monica feels more isolated than ever now that she’s back in her childhood home, with her webcam clients and the men she flirts with online being her only points of connection beyond the family that threw her out. The enormously talented Lysette conveys that unspoken pain so well, but it nonetheless struck me as a bit unrealistic, that a woman like Monica, who’d had to learn how to survive on her own from such a young age, would now, as an adult living in a city on her own, have no friends or community to speak of, much less speak to.

Maybe that hadn’t always been the case? Maybe, over the course of her relationship with that shitty ex-boyfriend, he’d isolated her from whatever family she’d cobbled together while in exile from suburbia, thereby leaving her with no one to turn to after they broke up, save for a crackling voicemail greeting that never says anything back. Or maybe that isolation was simply a narrative oversight on the part of the filmmakers, both of them queer though neither of them trans women. Perhaps they grasped the nuances of Monica’s childhood, the part of her life that most resembled their own, far better than they did the years that followed, which could have led to such details escaping them.

That latter reading, of course, is pure speculation. But I thought it made sense, and as we shuffled out of the theater while the credits rolled, Mike said he did too. Mike and I had met about seven years ago, though we’d followed each other online for a bit longer than that. I’d been dating an acquaintance of his at the time, and he was dating Kay, someone who would later become a good friend of mine. I’m grateful to say that I’m still friends with Kay, given how easy it could’ve been for us to fall out in the wake of our boyfriend rehoming. The first time I ran into her after Mike and I started dating was at a trans fundraiser party held every month in Queens. We talked a little at the bar, though not about you-know-who, neither of us daring to broach that potentially vibe-killing subject before we’d downed a few drinks. It was only later, while smoking together in a quieter corner of the backyard, that we finally cleared the air, so to speak, and thank god we did. She didn’t hate me, I was relieved to learn. Her main concern was maintaining our friendship; that was mine as well, and I told her as much.

The mood now lightened and much of the tension relieved, I’d joked that “it’s like the writers of Trans Brooklyn Sitcom decided to shake things up for season 5.”

She’d laughed. “I mean, there’s only so many characters.” An ironic estimation, given the setting—a nightclub packed with a couple hundred other trans people—but beyond the four-block radius, not untrue.

After exiting the theater, Mike and I tossed our concessional detritus and parted ways to our respective restrooms. I reemerged first, so I stood by the door to the men’s room while I waited for Mike to join me. The door swung open, and two older men who looked to be about in their sixties walked out, evidently in the middle of a conversation that they’d started on the other side of the door.

“—there was no scene where you see Monica when she was a man,” one of them said to the other as they passed, “so it felt unfinished . . .”

It was, without a doubt, one of the stupidest things I’ve ever overheard in my life. His words were a cold slap of reality; while I was sitting there in that theater, engaging with the specifics of a film’s depiction of contemporary trans life, some other guy sitting a few feet away had decided to give it, like, two or three stars because he didn’t get to see a “before” pic. It was like he’d come into the theater with a hardwired idea of what a trans woman is and what her narrative should be. And when Monica failed to deliver on that, presenting instead a more intimate slice of one fictional trans woman’s life, however flawed it might have been at times in its execution, he failed to see her entirely, just as he failed to notice the trans woman standing outside of the men’s room, doing everything she could to not burst out laughing as she caught this rare glimpse of the cis mind at work.

When Mike walked out a minute later, I told him what I’d heard. Mike, too, had been eavesdropping on the two men while he was in the men’s room, and after stitching his half of their exchange onto mine, we laughed our way out of the theater, lost in hysterics by the time we touched sunlight. It can be so frustrating, not being seen, whether literally or in that other, more annoying sense of the word. But it’s times like these that remind me how much fun you can have away from the spotlight, cackling in obscurity with those others standing just out of frame.