Excerpt

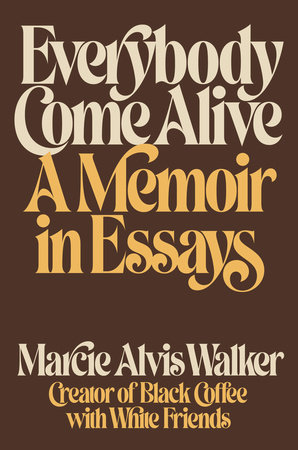

Everybody Come Alive

Chapter 1

RootsWhen I was five years old, Nada, my mother, put me in the back seat of the car, and we headed twenty minutes outside Cleveland to the doorstep of my paternal grandparents, her ex-in-laws, where after a few moments of polite chitchat about the traffic and the weather, she left me there for good.

I was five and unaware that her goodbye was a permanent handoff. I was the last of her five babies that she’d treated this way, relinquishing us into better hands with her blessing. Apparently, it’d been decided that it would be better for us to live with our grandparents during the school year because, according to my mother, the schools in their all-white neighborhood were better than the ones in her Black neighborhood. The schools in my grandparents’ all-white district had newer textbooks, larger libraries, well-equipped science labs and arts programs, and no more than twenty or so kids per classroom.

But I hadn’t been told any of these reasons. Adults back then didn’t need to explain their actions to five-year-old children. So I was left by my mother and confused, waiting for her to return later that day. She never did return to pick me up and take me home again. She returned only to visit. But mothers aren’t supposed to visit. They’re meant to stay.

For the first few months with my grandparents, I stopped talking—or to put it more accurately, I spoke very little, mostly only when I was spoken to. My trauma was very still and very quiet. You would not have known it was there. I just seemed like a well-behaved and compliant kid.

But I’d reasoned that if I was quiet enough, the pain and confusion of abandonment would stop moving. That’s the thing about being abandoned: it’s always happening to you. You are forever being left. Every day that Nada, my mother, didn’t come back was another day of her deserting me. Even when she was visiting, she was always gathering her purse and her keys to eventually leave me again. Her slim figure was good at slipping out and away.

To this day, in many ways, I’m still waiting for my mother to come back for me.

Throughout my childhood, my racial narrative was split between two stories. One story took place during school breaks at my mother’s house in a neighborhood glazed in Blackness. The other took place during the school year at my grandparents’ house in a neighborhood washed in whiteness.

My mother’s and my grandparents’ neighborhoods were only eleven miles apart. In the space of twenty minutes or less, my entire existence would be transformed. But no matter where I landed, I was the darkest spot on every page of both my stories.

By the time I was seven, the last white family on my mother’s block had long since flown the coop. And we kids, the Black descendants of the Great Migration, never noticed, too hard at play—organizing hide-and-seek, negotiating kickball as if we were getting paid to do so. We rode our bikes up and down the street to the corner penny candy store, then around the corner to throw rocks at the busted-up old abandoned house that looked like it might have been pretty back in the day when surely someone white and wealthier than all of us combined had lived there. We did this the whole livelong day until the first streetlight glowed, calling us home. I didn’t know a kid on that block who didn’t have enough. I didn’t know a kid who wasn’t at least fairly happy. At times, I figured I was the least happy of our bunch because I longed to be in only one story—the one punctuated with my mother, dark and lovely, infused with light. A world flooded with Black faces and Soul Train and even Black hair commercials.

My mother’s neighborhood was the color of every kind of rich, deep, lush brown that Crayola had not yet discovered. It was a far cry from being hood, but it spoke its language. Every adult on our block worked a J-O-B with benefits and a pension. So they’d all made it. Some bought Cadillacs and leisure vans to celebrate their success of having good credit. Every household had a father and a mother. Every mother and father dreamed of their kids going to college, or of buying a second car, or even taking a real family vacation.

Our home started out just like our neighbors’: we were a young Black family with earnest dreams. Until slowly but surely its interior eroded. There was the divorce, soon after I was born, that led to no father in the home, and barely a mother, with terrible credit scores and rumors of terrible karma. It was said behind closed doors, throughout the neighborhood, that we had it coming. Our father was loud. Our mother wore hot pants when she gardened. Our doom was imminent.

Despite the little rain cloud dribbling on our roof, my mother’s home was as neat and tidy as everyone else’s on our block, but with much more flash and flair. One wall of the dining room was tiled with mirrors. My mother had reupholstered the sofa and love seat with a dark forest-green velvet. It was as bedazzled as a Hilton Hotel, if the design inspiration was the Shaft movie soundtrack. It was an ever-changing design palace of fiberglass and wicker crammed into no more than twelve hundred square feet, with a galley kitchen, a small dining room, a living room, three bedrooms, and one solitary bathroom. She knocked out our front door and replaced it with a sliding glass door. She took down a pony wall in the kitchen—I imagine with her bare hands. “I was always trying to make it seem bigger,” she told me one day as we reminisced about that house while watching Extreme Makeover: Home Edition. My hot-pants-clad mother was a woman ahead of her time.

And she was gorgeous. I was totally and completely intoxicated by her. So were the mailman, my older sister’s boyfriend, and the pharmacist at the drugstore. And though they wouldn’t admit it, every other woman-of-the-house on the block kept a close eye on my mother and their husbands.

But she was also color-struck with a mad crush on the the-darker-the-berry-the-sweeter-the-juice kind of Blackness. She was befuddled at the world’s preference for lighter and nearer-to-white-Jesus skin tones and blatantly favored those who were darker. So much so that she preferred the dark-skinned man who would be my biological father over her husband. She became pregnant with me by this other man while married to my “supposed” father, who was very, very light-skinned, the boy she’d married when they were teenagers. She’d married him because he was from up north and would take her out of the Jim Crow South. And as far as I know, for at least a little while, they were happy enough and had all four of my older siblings, who were a beautiful spectrum of warm, soft browns. They were her kids. Beautiful, beautiful kids. But my mother felt she couldn’t see herself in the lighter skin they’d inherited from their father.

Her color-struck crush wasn’t my mother’s only affliction. As far as we know, all her life she displayed a range of symptoms that suggested a serious but undiagnosable mental illness. As she got older, her mental health deteriorated and her color-struck behaviors intensified. In her eyes, anyone lighter than a brown paper bag was born of the devil, and anyone darker was divine. This caused a lot of heartache for my sisters, who were fairer-skinned, as well as for my “supposed” father and extended friends and family. It even put them at risk when her psychotic symptoms were heightened.

And for me, her dark-brown-skinned love child, her favor confused my identity. “You are the Bride of Christ,” she’d whisper to me. “He’s coming back for you.” It was a lot of weight to put on my small, underdeveloped shoulders. I was terrified of such a wedding day. She prayed for his coming, while I hoped he’d forget our impending date. But that was my mother’s unique talent. She knew how to press weight onto fragile things without shattering them.

What my mother’s house lacked in space, she more than made up for with a bell-bottom-go-go-boots-and-afro kind of pizzazz. Colors and patterns swirled and blurred together everywhere. Burnt orange, poppy red, turquoise, and chartreuse green were some of her favorites, and when in doubt, she always went with a dash of mustard or dandelion yellow. Every surface was topped with glass. It was so fancy but a disaster for us kids who wanted to reach out and touch our reflections on every Windexed surface. Of course, like any self-respecting mother of her time, the house was hers, not ours. Promptly after breakfast, we were always ushered outside to play. A home built around the needs of a child was just not yet a thing. Home was where we learned to keep our hands to ourselves.

In the living room, next to a record stand with a record player and speakers, there were crates of records: Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin, Natalie Cole, the Commodores, Parliament, the Jackson 5, the Spinners—hundreds of records—Curtis Mayfield, Rufus and Chaka Khan, Al Green, Rose Royce, the Isley Brothers, and Earth, Wind & Fire. We weren’t allowed to touch them.

There were handmade ashtrays shaped like lava next to gourd-shaped lamps, and next to them stacks of magazines—JET, Ebony, and Essence—each one featuring beautiful brown faces. My mother subscribed only to the holy trinity of Black pride publications. We weren’t allowed to touch them.