Excerpt

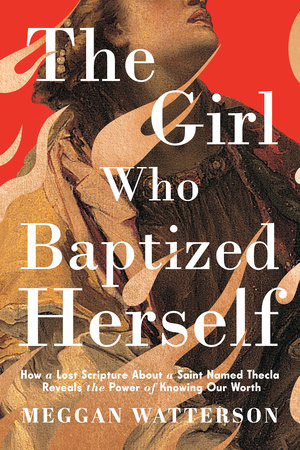

The Girl Who Baptized Herself

1.Her NameLet’s start with this—a teenage girl is sitting at her bedroom window listening to a man share stories with a crowd next door. She’s riveted by every word he says. And even though her mother and fiancé plead with her to stop listening, she refuses to move.

This man she’s listening to is talking about a world that’s entirely foreign to her, an inner world of freedom that will allow her to define her own life. And he’s talking about love—not a love she has ever witnessed before. It’s not a love that claims, but a love that liberates. It’s not a love that asks anything of her, except to be true to who she actually is within her. And what’s so radical about this world she hears him talking about is that it’s open to everyone, including her.

There are no bars on the window she looks through, and her bedroom door is not locked. Her family has some material wealth, so she isn’t suffering from a lack of practical things. But she’s also far from free.

Her name is Thecla, and her story takes place in the mid-first century in an area of the Roman Empire that is present-day Turkey, where a girl like her would have little to no power according to the world around her. The man she is listening to outside her window will later become known as Paul the Apostle, one of the earliest followers of Christ. And the scripture where her story is found dates back to 70 C.E. and is titled The Acts of Paul and Thecla.

Her story, for me, reads like a lost gospel for finding our own source of power within—a power that allows us to know who we are and to make choices for our lives based on that knowing. Rather than perpetuating the relentless pursuit of trying to fulfill the expectations of others. And rather than letting the past dictate our choices in the present moment.

Thecla’s story, and the scripture where it’s found, suggests that women held positions of spiritual authority from the start. And it suggests that this earliest form of Christianity was about defying the patriarchal power structures that exist in the world, powers that seek to legitimate the idea that some of us are greater or less than others.

What becomes apparent when we take The Acts of Paul and Thecla seriously is that Christianity before the fourth century wasn’t an institution, or even a religion; it was far closer to an ancient version of an equal rights movement.

So, what happened?

As a feminist theologian, I often feel like an archaeologist. I have to sift through the rubble of the erasure that Christianity underwent from the fourth century onward. I must read between the lines of the scripture within the New Testament for the scripture that I know is missing. I have to unearth what has always been there for us to find but that we’ve never been told existed.

I wasn’t raised Christian; I was raised feminist. I inherited a sacred rage from my mother. And she inherited it from her grandmother. It’s a rage at the refusal to be satisfied with a world that doesn’t reflect the inherent worth of every human, or with language that doesn’t actually name us.

I was taught to see and say the hard things, the unspoken things, to never fear a configuration of words that hasn’t been said out loud before. I was taught that there’s a rage love inspires that’s the opposite of destructive. It’s a creative force among those who have been silenced that feeds the resolve needed to trust in something unseen, unrealized in the world around us. It keeps us from accepting that this is just “the way things are.” It’s like an undiscovered fire inside us to insist on a world we can all imagine but haven’t found the words yet to make visible.

So the cross signified more than faith to me. It also meant justifying slavery, genocide, the erasure of cultures; it meant generations of Native American children stolen from parents; it meant deifying the subjugation of people based on sex, race, caste, and gender. It meant controlling or taming women; it meant shaming sexuality; it meant Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne and her scarlet letter. It meant condemning people for being anything other than heterosexual. It meant covering up abuses of power for men of the cloth, and excusing abuses of power for husbands over wives. It meant the Magdalene Laundries in Ireland, where girls had to do penance for being unwed mothers. It meant an adoration of an unattainable feminine ideal, and a desacralizing of the actual human reality—the sweaty, messy, bloody reality of the form of human body that reconstitutes the world, the form of body, ironically, that actually most closely mimics the divine power to give life. It meant unchecked authority; it meant immunity from any sort of real justice. It meant an absence of mercy when mercy was most needed.

The first time I read the New Testament as a little girl, I broke out in hives. I felt this intensely confusing mix of emotions. Before I understood what the word “feminist” meant, with little girl clarity, I was finely attuned to detect inequity. So when I went to church, and encountered this idea in the New Testament of a father god—and a father only—and that this male-god then gave some sort of holy decree for only male apostles and male bishops, and an exclusively male succession of divine authority going all the way back to Christ, I just sort of raised an eyebrow and quietly called bullshit inside me.

That inner sense, that inner knowing that there had to be more to this story, this is what led me to want to find the scripture I knew must exist somewhere.

And I knew this not because of any research or scholarship, not initially anyway. I knew this because of the love that liberates. And although there aren’t words to adequately describe or name what I mean by that phrase, I will attempt to explain it in chapter four. For now, let me just say that this form of love I’m referring to wouldn’t let me walk out of church, hive-covered and angry, and keep on walking. This love, which is more than an emotion or a feeling, is like a presence that came with me when I left.

French philosopher, mystic, and political activist Simone Weil described her spiritual position as located “at the intersection of Christianity and all that is not Christianity.” This is true for me as well, except for this one edit: I stand at the intersection of Christianity and all that is not yet Christianity again.

Religious scholars refer to the earliest Christian communities as “the early Jesus peoples” or “early Christ movements.” I refer to them collectively in this book as the Christ Movement. These ancient communities were so threatening to the Roman Empire that Christ was crucified for sedition, and everyone associated with him was persecuted. And for hundreds of years, up until Constantine claimed Christianity as the empire’s religion in the fourth century, to call yourself a Christian meant being sentenced to death.

Why?

Women and girls, like Thecla, within the Roman Empire in the first century had little to no rights. Depending on their wealth and social status, women could accrue influence—secretly, behind the scenes, persuading their fathers or husbands—but they did not have direct power. Women only had access to a vicarious power. A proximal power. Because no matter their status within the Roman Empire, women could not vote or hold political office.

Thecla was not allowed to choose a life of her own. And this is critical context for us to understand before hearing her story. She was her father’s property, then she would become her husband’s. And her children would be theirs, her husband’s and father’s, not her own. It was a revolutionary act then for women within the Christ Movement to consider themselves equal to men, and equal to one another—to call each other sisters—even if one was enslaved and the other was married to a wealthy man with political power.

From the fourth century onward, the radical, highly persecuted Christ Movement that began in the first century was tamed and transformed under Emperor Constantine to look far more like the systems of power already in place within the Roman Empire. The systems of power that rank humanity according to a hierarchy of existence, with the emperor way at the tippy top, and women and slaves with little to no power down at the bottom. In short, the Christ Movement became patriarchal. But it did not begin that way.

In 313 C.E., by a single edict, Emperor Constantine converted the Christ Movement to the empire’s religion. By 324 C.E., he had assumed sole control over the empire and used the Chi-Rho, a symbol formed from the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ, on the shields and military standards of his warriors in battle.

Beginning with the Council of Nicaea, a council of Christian bishops convened by Constantine in 325 C.E., the church under the Roman Empire took all of the scripture that had so much to say about finding a source of power within us—a power greater even than the emperor—declared it “apocryphal” or “of doubtful authenticity,” and then ordered for all evidence of it to be destroyed by the end of the fourth century.