Excerpt

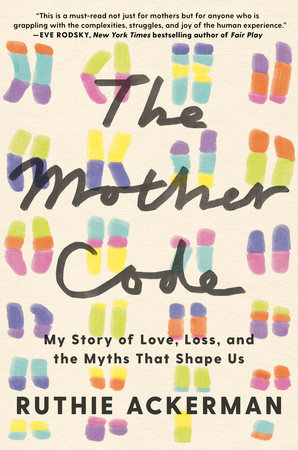

The Mother Code

1 My Ancestors, MyselfI come from a long line of women who abandoned their children. Or at least that’s what I’d been told.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve heard about how my great-grandmother Kitty and my grandmother Ruth ditched their kids because of men or money or mental problems— or all of the above. As the story goes, Kitty left her son and daughter with her in-laws so she could gallivant around Europe, “man hunting,” as my mom calls it on a good day. On a bad day, my mom will let it all hang out. “Kitty was a gold digger,” she told me recently when I called to let her know that I’d been researching the women in our family.

We were on video so I could see my mom’s face. The way her lips curled in disgust when I mentioned Kitty’s name. “What you don’t understand is that all Kitty cared about was money,” she said. She’d marry one rich man only to leave him when she met another man who was even richer.

As I listened to my mom, what I heard was the conviction in her voice. She was certain that her take on Kitty was “true.” There couldn’t be any other explanation for my great-grandmother’s behavior. Kitty was cruel to her children and her grandchildren and money was the culprit. End of story.

“She was married twenty-five times,” my mom said. “I know it sounds crazy,” here’s where she rotated her finger several times next to her ear, the universal symbol for cuckoo. “But she was.”

I shook my head. Twenty-five times sounded ludicrous. Impossible. Yet, despite all the hyperbole and hysteria about Kitty, the stories about the men she loved and left as quickly as a mouse can snatch a piece of cheese from a trap, I later learned that there was some truth to the family legends. Over the years, I interviewed an aunt, an uncle, and a cousin. I even spent a weekend in Baltimore with Kitty’s son before he died. “Kitty didn’t want to be a mother,” he told me unequivocally, which is something I’d never heard anyone admit out loud about a woman. Especially one who became a wife for the first time in 1917, when women were meant to worship their husbands and children.

Much later, I searched through census records, old newspapers, marriage and divorce decrees, and immigration files. I learned Kitty went by at least five first names: Kitty, Kune, Katie, Kate, and Katherine.

Eventually, I could decipher facts from fables. I dug up documentation for fourteen of Kitty’s marriages. Her shortest was only ten days. She married my great-grandfather Irving twice, the first time at just seventeen.

My grandmother Ruth followed in her mother’s footsteps, abandoning her first child, Beth, to marry my grandfather.

The truth is this: I’d always secretly rooted for Kitty and Ruth, though I never told anyone in my family. I assumed that everyone denigrated them because they roamed around for their own pleasure, as if there was anything wrong with that. But I understood that of course there was. A woman living her life for herself has never been allowed.

Women at that time didn’t choose whether or not to be mothers. What would choice have even meant for my great-grandmother and grandmother when the system—their family, their community, their religion, the culture they were steeped in—only showed them images of women as mothers? Mothering was natural. It was normal. There was no question of desire. Or a path for opting out. They could only choose to mother as much as a fish chooses to live in water. It’s what they had to do. It’s what women did.

We now have a language, a lexicon, for maternal ambivalence, but back then, back in the early to mid 1900s, women were mothers, and that was that. Yet Kitty and Ruth always scoffed at the rules, which is what I admired about them.

The problem with public records is that the emotional tenor of the past is erased. I have no idea if Kitty loved any of her husbands (or if Ruth loved hers). I have no idea why Kitty left them, or if, perhaps, they left her. I have no idea if she was looking for money from them or some other type of security. I have my guesses, though. Citizenship was a priority for a Jewish girl who spoke only Yiddish and never went to school after arriving at Ellis Island in 1906 at the age of just six.

It may be true, as my family tells me, that Kitty married a Chicago gangster then divorced him because Chicago was too cold. Or that she married the owner of a jewelry store empire in South Florida and left him when his business went kaput. And then finally in her nineties, living out the last of her days in a nursing home, she married the man, several decades her junior, whom she called “what’s his name.”

Everything I know about Kitty and Ruth has been passed down to me through a web of grief and sorrow. It’s like the Indian parable of the blind men and the elephant. In the parable, none of the blind men had encountered an elephant before and they could only imagine what one looked like by touching it. But each man felt a different part of the elephant’s body. One man felt the side and determined that an elephant is smooth and solid like a wall. The next man felt the trunk and thought the elephant was like a giant snake. The third man felt the pointy tusk and decided the elephant was deadly like a spear. The fourth man felt the tail and figured the elephant was like an old rope. The lesson of the story is that each man could only see the world through his own personal experience, and yet we all use our partial point of view as the whole truth.