Excerpt

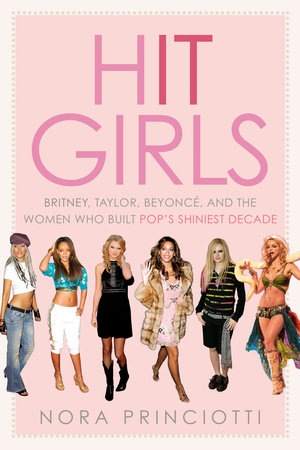

Hit Girls

1How Britney Spears Ended the NinetiesThe dawn of the twenty-first century was characterized, primarily, by something that did not happen. I have some fuzzy recollections of Y2K, the panic at the end of the 1990s that ensued after a handful of computer scientists raised concerns that the new year would bring mass system failure and worldwide chaos since computer code, which categorized what year it was by the last two digits of the annum, would be unable to tell the difference between 1900 and 2000. As I write this, I have an espionage instrument of the Chinese military in my pocket that I use to watch cat videos and Jeff Bezos controls my supply of toilet paper, so all the fuss seems kind of quaint, but I am told it was a Whole Big Deal. In 1999,

Time magazine ran an issue with the words “The End of the World!?!” on its cover. But then, Y2K arrived with little incident. The lights stayed on. Trains ran on time. Society remained intact.

Which . . . obviously. The changing of a clock does not define a new era. Only Britney Spears can do that.

On September 29, 1998, Jive Records released Britney Spears’s single “. . .

Baby One More Time” to contemporary hits radio stations across the United States. Though the calendar wouldn’t flip centuries for another fifteen months, the moment those glottal oh baby, babys hit the airwaves was the moment that the aughts began in pop culture and in music. But “. . .

Baby One More Time” and the birth of Britney as the defining pop star of the 2000s was more than just a kickoff event. Before the aughts could become a period in which pop stardom changed, they had to become an especially fertile one for pop music in the first place, and it was Britney Spears who made sure they did. By creating an indelible pop classic, clearing Max Martin’s path to become the defining producer of the decade, and by using provocation to reach older and broader audiences than the teen pop of the late 1990s, Spears paved the way for pop music to flourish in the early 2000s.

Let’s set the stage a bit. The day before “. . .

Baby One More Time” debuted, Aerosmith’s “

I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” was the number-one song on the Billboard Hot 100 and had been for a month. Filling out most of the lower rungs of the chart was a mix of radio-friendly country (Shania Twain, LeAnn Rimes, Faith Hill), hip-hop and R&B (Usher, Brandy, Puff Daddy), and a smattering of Third Eye Blind–variant rock bands.

Radio had been in a bit of a bind. Grunge had dominated the midnineties, and while Radiohead, Nirvana, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Pearl Jam were the biggest bands in the world to the MTV audience, their themes of alienation and dejection weren’t great mainstream radio fodder. Nirvana front man Kurt Cobain’s death by suicide in 1994 had been a turning point for artists, too—the genre lost its chief spokesperson, and the disaffection of its other leading men became harder to venerate when it had such fatal consequences. Grunge morphed either into nu metal, which made even less sense on Top 40 radio, which on a national level was becoming increasingly homogenized thanks to conglomerate station ownership, or softer alt-rock, which was more palatable but less interesting. Few DJs felt like they were on the cutting edge spinning Sugar Ray during drive time, and audiences were dwindling.

In 1996 alone, New York contemporary hits station Z100 lost a third of its audience. The station fell into eighteenth place, in large part by leaning heavily into a waning alt-rock scene. A shake-up followed, and several new executives, including a young programmer named Sharon Dastur, were brought in to right the ship. On her first day, Dastur walked into the station and was surprised to find

Alice in Chains playing on the morning show and Soundgarden signed up for another guest slot. “I’m like, ‘What is this? This is not Top 40,’ ” Dastur told me.

There’s an idea in radio about how the types of sounds that are popular in music ebb and flow, particularly as it pertains to Top 40. It comes from a man named Guy Zapoleon, a fifty-year veteran of the radio industry and longtime Top 40 program director who now consults for stations. In 1992, Zapoleon published an argument that, since 1956, the modern era of popular recorded music could be explained as a cycle with three stages repeating itself roughly every ten years. Zapoleon argued that the cycle begins with a “pure pop” stage, where there’s a supply of good pop music with mass appeal, as well as rock, hip-hop, and R&B that bleeds into pop. The pure pop stage is the best stage for a Top 40 radio programmer. The second stage that follows is what Zapoleon calls “the extremes,” in which music moves toward its edges, usually alternative rock and hip-hop, looking for freshness and innovation that younger listeners enjoy but loses something in mass appeal. For a radio programmer, the challenge of “the extremes” is that a good amount of the most relevant music doesn’t quite fit on Top 40 radio. This leads to the third stage, “the doldrums,” where pop is dull and overwrought, cut off from the edgier happenings in rock, R&B, and hip-hop, and flounders until there’s something, or someone, fresh in pure pop to bring the cycle back around. And in the late nineties, pop radio was deep in the doldrums.

But cycles being cycles, a new one was around the bend. Zapoleon considers its starting point to be 1997 with the arrival of the teen pop wave and, specifically, the arrival of the Spice Girls in North America. The girl group had been initially shortchanged as a euro phenomenon that would never work in the United States, historically snobbier when it comes to bubblegum pop than European countries, but this proved incorrect quickly. Sporty, Ginger, Posh, Baby, and Scary had “

Wannabe” at number one on the Hot 100 for four straight weeks in January 1997 and their debut album Spice sold at least twenty-three million copies.

It’s hard to overstate the degree of international megastardom the Girls achieved, seemingly, overnight. The same year Spice hit America, the Girls visited South Africa for a charity concert and met Nelson Mandela, who called them his “heroines” and told reporters that meeting them was one of the greatest moments of his life. In an attempt at some good PR in the wake of the death of Princess Diana, then Prince Charles attended the concert and brought along a young Prince Harry, who was nursing a bit of a crush on Geri Halliwell, a.k.a. Ginger. It’s a sadness to me that Peter Morgan’s Netflix series The Crown never did anything with this material; reportedly, one Spice Girl grabbed Charles’s butt during their meet and greet, and I can only imagine how Dominic West would have played that moment. Ultimately, Charles’s attempt to seem like less of a fuddy-duddy backfired when the British press determined that Diana never would have made Harry wear a suit to a Spice Girls show, but the young prince did get to meet his fellow Ginger. Halliwell also had a notable moment in her closing remarks at the concert: “I think there’s a classic speech that Nelson Mandela did, I can’t remember exactly, but he mentioned never suppress yourself, never make yourself feel small for others’ insecurities,” she said. “And that’s what girl power is all about.” Hear, hear, Geri—no notes.

In the United States, the fact that audiences embraced Spice did seem to indicate that they were ready for a new pop movement. Two years earlier, in 1995, the producer Clive Calder and infamous boy band manager Lou Pearlman had tried to debut the Backstreet Boys with “

We’ve Got It Goin’ On.” But while the song was a hit in Europe, it got no traction for the group on US airwaves. In June 1997 they tried again, releasing “

Quit Playing Games (With My Heart)” as a single. This time, with more and more of the children of baby boomers coming of age every day, we were ready. By August, the song was at number two on the Hot 100. Suddenly, the Spice Girls, Backstreet Boys, *NSYNC, and Hanson all became household names in America, and their mix of new jack swing rhythms and orchestral hits with croon-worthy pop melodies was all over the radio and MTV. Teen pop was a sensation, and because it capitalized on the last days of the pre-Napster era when CDs were flying off shelves, it was also staggeringly lucrative. Backstreet nearly matched Spice’s sales numbers with twenty-five million copies sold, and every kid knew which Spice Girl or Backstreet Boy they identified with, crushed on, or both. But as long as its audience was concentrated within one generation’s youth, it was destined to crest.