Excerpt

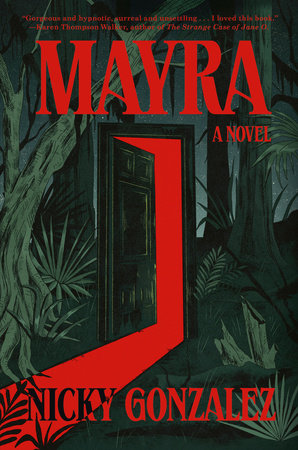

Mayra

1Mayra would do this thing with her mouth. As girls we’d sit on opposite ends of a three-cushion couch with our legs tangled beneath a blanket, the watercolor glow of the TV painting our faces. She’d hook her lower teeth to her upper lip and work her jaw until flakes of dead skin chipped away and disappeared down her throat. Chewing like that, with her jaw stuck out in an underbite, glowing in an otherwise dark room, she reminded me of an anglerfish. I couldn’t help but stare. Until then, all the beautiful women I’d met acted as though they were being watched at all times. My mother, for example, always left the room to blow her nose, no matter how intimate her relationship with present company. Mayra drew the eye, but she either didn’t know or didn’t care. Girls like me, though, with sandpaper complexions and tight-lipped smiles, could afford to be uncouth from time to time. Back then, nobody was looking at my small mouth, my thin legs.

When her name lit up my phone screen on a Wednesday night so many years later, an anglerfish still came to mind. My belly warmed and turned as the phone’s vibration sent ripples through the mug of stale coffee resting beside it. I tended to ignore calls from old friends and acquaintances. Too often, I’d get my hopes up, charmed by the rare friendly gesture, only to have the pretense of polite conversation ruptured five minutes in, when the caller revealed themselves to be part of a pyramid scheme. It always began friendly enough, but then the questions crept in—was I in the market for leggings with pockets? iron supplements? a cream formulated specifically for dry nostrils?—and it always ended with me feeling a great deal lonelier, thirty fewer dollars to my name.

It had been six years since I’d heard Mayra’s voice, more since I’d seen her in person, but our friendship had been the kind of telepathic bond that most people only feel once or twice in their lives. If she wanted to sell me vitamins, I’d let her. I picked up.

“Ingrid, you answered,” she said. After all this time, hearing her voice blew a hole right through me.

“Of course,” I managed.

We recited hollow how-are-yous.

“I’d like to meet up,” Mayra said, simply. I asked if she was in town, and she said, “I will be. Kind of. I’m getting in tonight.” Her voice was so clear it was eerie, and when she told me where she was headed—just southeast of Naples, the middle of the swamp—I imagined her speaking to me from a screened-in porch in an empty field, miles of sawgrass muffling the skittering of every reptile. She was done with her graduate program, she explained, and planned on taking some “me time” in a remote house, walled off from everything, to clear the muck from her mind before reentering the workforce. She wanted me to join. I pictured something advertised as a “cabin” because of its log-siding exterior, while on the inside boasting ten fully renovated bedrooms, a saltwater pool, a home theater.

“You’re still in Hialeah, right?” Mayra asked.

“I am.”

I heard pity in the way she said, “Oh.”

“It’s super nice. A one-bedroom,” I said, “all to myself. And I have a garden.”

It was a studio apartment and the garden in question was a wilting basil plant on the kitchen windowsill. If I were to draw up a listing for it at work, I’d call the floor plan “efficient.”

“A garden? How do you keep people from stealing your vegetables?”

“I don’t,” I said with some force.

“People used to steal my grandparents’ mangoes,” Mayra said.

That was not the same thing at all. A yard peppered with mangoes destined to rot in the south Florida sun begged for someone to hop the fence and do some cleaning up. It was hardly stealing. It was a public service. My blood fizzed and popped—this kind of offhand comment about our hometown reminded me why our friendship had faded. After undergrad in upstate New York, Mayra regarded Hialeah the way a gringa would: what a quaint little place, what potential. But I felt bad for people who lived anywhere else. Where else could you find a four-dollar medianoche the size of your head? Where else could you open a window and eavesdrop on three different conversations without even having to hold your ear to the screen? Where else, four beers deep, having come home after half-watching the Heat game at Flanigan’s happy hour, would you find a green anole perched on your showerhead, bobbing its head to the salsa blasting from a neighbor’s yard?

“So what do you think? You coming?” she asked.

“Naples is kind of a drive for me. Can’t you drop by? Are you flying into Miami?” I asked, knowing she’d say no. Being back home made her squirm, accustomed as she had become to northerners who talked so softly, they practically spoke in whispers. The last time we hung out, when two women on the other side of the pants aisle of Red White & Blue Thrift Store began arguing about who had seen a particular pair of canary-yellow leggings first, I watched her hands shake as she pushed hangers along the rack. If she had been in a car, she would have locked the doors. I knew she’d rather chug a pint of swamp water than ever come home, but I wanted to make her say it.

“I’m actually driving. I’m in Gainesville these days.”

“Gainesville? Since when? I thought you were up in Vermont or something.” That she’d never live near Miami again was a given, but even Gainesville, a five-hour drive north, seemed too close. I assumed the entire state of Florida, for her, had a repellent radius of at least five hundred miles.

“I’ve never lived in Vermont? But close enough, I guess. I’m at UF now. Or I was,” she said. “So what do you think? I’ll get there tonight, and you can come anytime after that. Explore with me? Catch up?”

“Maybe,” I said. There’d been a period of my life when I’d have done anything for that much alone time with Mayra.

“Come on. When was our last sleepover? Think about it.”

“I have work, though,” I said.

“Where do you work these days? Can’t you take a day off?”

I could. I had sick days and personal days now: a blessing, a miracle even, after five years of processing returns at the same Kohl’s Mayra and I used to steal from.

“I work in real estate,” I said.

“You’re an agent?”

“Mhmm,” I answered. I was an assistant, but I didn’t want to demote myself in Mayra’s mind.

“That means you, like, sell houses that’ll be underwater in twenty years?”

So there was still no winning with her.

“I guess, bro,” I said, “but it’s just a job. A lot of these assholes are so rich they buy these places and barely even live there, anyway.”

“You have any tours scheduled tomorrow?”

“No.”

“Okay, so, tomorrow? Spend the weekend,” Mayra pressed.

“I have a date tomorrow.” That was true.

“A date! With who?” Her voice became low, conspiratorial. The tell me everything tone. Except there was nothing to tell. A middling man I’d matched with asked me on a first date, and I said yes, hoping he’d surprise me.

“His name is Brian,” I said. “He’s amazing. I think it’s going really well. We’re still kind of in the honeymoon phase, so I’ve really been looking forward to tomorrow night.” My text chemistry with Brian over the past couple of weeks had ranged from mild to medium. He enjoyed watching Westerns and going to the gym. Two beige flags.

“And after the date?” she asked. “Can’t you come on Friday?”

I said I’d think about it.

“How about you let me give you directions now in case you do decide to come. I don’t know how good service will be out there, so you should write this down. In case you can’t reach me.” Mayra recited the directions haltingly, as though she was reading them for the first time herself. My phone would only get me so far, she said, and after that I’d have to follow the instructions I was jotting on a sticky note: left at a fork, five-mile stretch of swamp, left again at a marsh, and twenty-odd miles later a right onto a gravel road that was easy to miss.

“See you soon, I hope,” she said.

I looked her up as soon as the call ended. She used to be easier to stalk, back before she became one of those social media minimalists who posts once per century. Once upon a time, every hot chocolate, every study session, every jaunt off campus had its place on her feed. Which was how I’d found out, well into her junior year, that she was visiting Hialeah. It was a selfie. A preset filter failed to offset the flat, cold lighting of the room she was in, and as a result her skin looked grayish green, a corpse color. Even so, I could see why she’d posted it. She had a puffy, fresh-out-of-bed look. Casual and cuteiful. I may have even liked it except that, off in a corner, I saw one of La Carreta’s branded paper placemats. I waited days for her to reach out, but she never did. A whole visit home and she hadn’t even tried to link up. I took it for what it was: a nail in the coffin, a big fat “f*** you.”