Excerpt

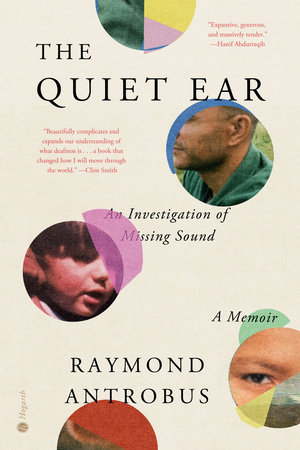

The Quiet Ear

1The Frequencies Are YoursLet me go back then, to the sounds of my birth.

If I close my eyes, the sounds of my birth come from a million places at once. Wind in the trees by the beeping traffic on the main road, the shrilling bike bells under the canal bridges, the bustling markets, trolleys rolling over grazed pavements, the clanging of the market-stall bars, the “pound a bowl, pound a bowl” yelling, road works drilling, digging, engines whirring, shutters clanging, the shovels coming down on the hot tarmac, the pop and crash of the lifted manhole covers, the radios blaring in the cars and the offices and the open living-room windows, the dogs barking, the rivers running, voices on the train carriages and the buses, bars, galleries, benches by the lake, children on the climbing frame and children who have tucked themselves into the huts and the tunnels on the adventure playgrounds.

They come from the families standing out in the fields clapping as the children’s kites flap in the wind, the coo-coo pigeons, the chirp-chirp sparrows, the man scattering seeds beneath the Trafalgar Square lions. The trees with their branches and leaves stretching past the windows of the hospital wards and corridors as if saying now or live or breathe or hear hear hear.

In 1986 in Homerton Hospital, London, a midwife clicked her fingers next to my newborn ears and gauged my response. It was my first hearing test, and I passed.

There were so many sounds that existed that I would not hear until I was fitted with hearing aids at the age of seven. Until then, I existed in my own kind of noise.

For the first seven years of my life, it was assumed I was just slow or perhaps dyslexic. I would miss vital details in teachers’ instructions, which kept getting me into trouble, like being told I could play outside but missing the “come back in five minutes”; then, during the subsequent detention (a harsh punishment but the teachers thought I was deliberately disobedient), being told to write about why “punctuality was important” and composing a wonky-lined misspelled essay on the value of punctuation. I was constantly told that what I was hearing was wrong without understanding why, which meant I couldn’t trust myself or the world around me. How does a child make sense of words or the world when they seem slippery and untrustworthy? What new perspectives and sensibilities might open up during this formative period?

No one knew I was deaf until my mother bought a large, exceptionally loud, cream-colored telephone that sat in her living room like a pet. The phone rang and rang, and my mother looked at me, unresponsive to the shrilling.

This is how I was diagnosed as deaf.

At a children’s audiology clinic in Hackney called the Donald Winnicott Center, I sat in a small room with my mother and a serious-looking woman in a white, thickly knitted sweater. I was seven years old. I didn’t know who or what Donald Winnicott was but I thought he must be old because that’s how the clinic felt: brown and gray carpets in sterilized waiting rooms. My mother sat in the corner of that small, soundproofed room with padded walls. The serious-looking woman sat behind a big cream-colored machine with yellow and green buttons.

“Raymond,” my mum said slowly. She spoke to me differently when we were inside this building. Her voice slower, louder. I heard her as she looked at me, her face serious as she handed me a gray remote with one black button on it. “The doctor wants you to press this button when you hear a sound.”

I faced the serious doctor; her eyes were on the lights on her machine. Every now and then I heard a creepy sound, like a ghost whistling faintly, so I pressed the black button and the sound disappeared.

After the doctor turned off the machine she only had one expression: a look of concentration, with raised eyebrows and tight forehead, which held permanent suspense. It gave Mum a hard listening face when she looked at her, but it softened every time she turned away to look at me.

Mum and I sat, parked outside the clinic in her red Mini Metro. I knew she had something important to say because she put on both our seatbelts and didn’t start the engine. “Raymond, I heard every one of those sounds in that room and I didn’t see you press the button.” She looked scared, whereas I remember feeling deeply impressed that she could hear things that weren’t there. She didn’t explain what this meant, but the test had revealed the hidden nuance of my hearing.

Shortly after, I was fitted with my first hearing aids. In a school photo taken at the time, you’ll see I’m not wearing hearing aids. I would whip them out whenever my photo was being taken, mainly out of shame. In my childhood journals, I wrote that “hearing aids don’t suit me” because they highlighted my vulnerability and made me feel ugly, incapable, and “disabled.”

It was around this time that I began discovering my missing sounds: anything high-pitched—whistles, birds, kettles, alarms; “sh, ch, ba, th” sounds in speech—the slow vibrating wavelengths that were meant to be picked up by small hair cells in my inner ear; all of it missing.

My parents had to navigate this world of deafness for me. They were both hearing, as were all the medical professionals I met, and everyone emphasized my deafness as a “loss,” something that would require effort to manage in the hearing world. I would sit in audiology clinics or at the front of classrooms or even around tables in special educational needs (SEN) units and I would only be assessed and understood as someone struggling to hear.

Once, while I was being dropped off at school, a mother of one of my school friends told me my mother was overreacting by giving me hearing aids because I didn’t seem deaf enough. But my parents knew. They saw how loud I had to turn up the television, how often there were gaps in my understanding, and how I didn’t answer the door or the phone.

•

In 2021, within an hour of my son’s birth he was given a hearing test. His mother and I watched the doctors set up the machine as he lay wrapped in blankets, our eyes wide and unblinking as wires were attached to his ears. The machine whirred and beeped; his head wobbled. The doctor peered at the graph, muttered “Good,” and rushed away, the machine disappearing down the corridor.

I was anxious the doctors might have got it wrong. No one showed me my son’s audiogram; I had to take the doctor’s “good” word for it. But “good” so often fails to pick up nuances. “Good” failed me in this context. “Good.” That vague but affirming word, the word God used when looking over “all He had made.”

I began to wonder how my hearing son’s experience would differ from mine, and how we might understand or misunderstand each other. For over ten years I’d worked as a freelance poetry teacher, mainly in secondary schools. As a teacher I appreciated the need to scaffold ideas and model behavior; I wondered how I would do this for my son, and I wondered how I ever did it for myself.

Since my son’s birth, the African proverb “It takes a village to raise a child” keeps running through my mind. I take stock of my community, parents, deaf people, writers, artists—and I turn to Granville Redmond.

Born in the second half of the nineteenth century, Redmond was a Deaf painter, actor, and mime artist. Art critics at the time had different things to say about Redmond’s deafness and how elements of his identity were expressed in his paintings. They described his scenes as “muted” and “silent.” Some thought the loud color of his paintings was a result of his deafness, while others thought the quieter nocturnal paintings and tonalist paintings represented what Redmond called his “solitude and silence.” Much depended on who was writing about Redmond and what they projected onto him. Redmond, however, didn’t resist this kind of categorizing. He suggested that he had developed his style of landscape painting because he had experienced “the loss of other senses.”

Redmond’s full name was Granville Richard Seymour Redmond, known to his family simply as Seymour, the same name as my father.

On a virtual tour of Redmond’s 2020 exhibition (The Eloquent Palette), a painting appears of the exact scene I had seen in many of my dreams since becoming a father. It’s called Sunset Over Lake and is part of a series of nocturnal paintings Redmond created in the early 1900s.

Redmond’s paintings became known for their quiet scenes that cry out in almost psychedelic color, and yet there’s always something gentle about his touch despite the dramatic tones, particularly in his coastal landscapes of California. Violet, orange, yellow flowers are scattered in the foreground of many of his paintings; rocks and patches of earth between all the wild grass and plant life hinting at paths grown over. You can spend so much time taking in the vibrancy of the flowers alone (especially the golden poppies) that it takes a while to notice how often there is water, a shore, distant hills, and a bright sky keeping the same company, even taking up more of the canvas. On a Redmond canvas, beauty is as much the rock in the grit as the torn pieces of clouds in the sky. Every object in his landscape is rendered with his radiant spirit.