Excerpt

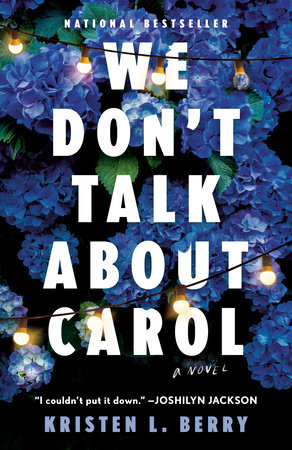

We Don't Talk About Carol

OnePresent Day“You sure you’re going to be able to pack up the house without killing each other?” my husband, Malik, asked, his warm, rich voice amplified by the rental car’s surround sound system.

I snorted as I drove out of the hotel’s garage and into sunny, leafy downtown Raleigh. “I can’t make any promises.”

“There’s really no one there who can help?”

“You saw how it was at the funeral. Grammy didn’t have any family left, just church friends as old as she was.”

“She had family,” Malik said. “She had you guys.”

I shook my head and felt my springy shoulder-length curls exaggerate the movement. “Our relationship consisted of exchanging birthday cards and calls at Christmas. Not much of a family.”

It had all happened so fast. Grammy had always been so spry and independent, it was easy to forget that she was ninety years old. And then last week we got a call that she’d had a stroke, and was in the hospital, unconscious. The next day, she was gone.

She’d told her dearest friends where she kept the folder with all the documents we’d need for this moment, including her will, life insurance policy, information on her prepaid cemetery plot, even a handwritten outline of what her funeral service should entail. All she asked was that my mother—her daughter-in-law, and the closest thing she had to a child now that my father was gone—oversee the process of clearing out and selling her home of over seventy years.

Recognizing what a gargantuan task this would be, and guilt-ridden from spending so little time with Grammy in the years leading up to her death, my sister, Sasha, and I immediately offered our help. And while I never would have asked him to, Malik, ever the doting and dutiful husband, rearranged his carefully constructed work schedule to join us on a red-eye from L.A. to Raleigh five days ago.

“I shouldn’t have left.” Malik sighed, the reverberation of the sound through the speakers sending goosebumps down my arms. “I can push my meeting and fly back out there.”

Something swelled inside my chest. Malik had spent weeks preparing for the quarterly board meeting of Wealthmate, the financial services start-up he founded. But I knew if I asked him to, he’d reschedule the entire thing. I was staying another five days to help my mother and Sasha with Grammy’s house; they’d book their return flights to L.A. when the house was officially on the market.

“Absolutely not,” I said. “I know how important this meeting is. We’ll be fine here.”

“Will you ask Grace or Sasha to help you with your shots?”

“Nah, I’ve got it,” I replied, though the tender flesh below my navel pulsed angrily at the thought.

“I know your mom can be a bit of a drill sergeant, but don’t be afraid to take breaks, or to go for a walk around the block if they start getting on your nerves. You know what Dr. Tanaka said about avoiding stress.”

My fingers tightened around the steering wheel.

Avoid stress. What was I supposed to do, lock myself in a spa until one of these IVF cycles finally worked? “Malik,” I said evenly, “I’m well aware. I was the one on the exam table, remember?”

“I know,” Malik said in a small, pained way that instantly filled me with guilt for snapping at him. “You’ve got enough going on without having to listen to me lecture you. I’ll let you go. Just promise to call if you need anything. I’ll book a flight, hire professional packers, send a rescue team out to extricate you, whatever you need.”

“I love that you actually mean that, even though you know I’d never take you up on it,” I said, smiling.

“If I offer to take care of you enough, one of these days you might actually let me,” he replied.

We hung up and the true crime podcast I was listening to resumed as I continued the drive to Grammy’s. She’d lived in South Park, a neighborhood surrounding Shaw, the oldest of the many historically Black colleges and universities in the area. I marveled at how different the landscape looked from L.A. Giant swaths of verdant land appeared untouched, and the ancient trees that towered over homes were so lush they appeared capable of swallowing the structures whole. Unlike the belligerently cheerful L.A. sky, the atmosphere above Raleigh seemed moodier, richly layered, thick with history.

As I pulled into Grammy’s driveway, I realized how much her house reminded me of photos I saw of her in her final years: aging yet elegantly kept. Grammy’s uncle had built the home back in the 1940s, when it was rare for Black people to own property in the area. The single-story structure was flanked by two-story new-construction houses of a particular style sprinkled throughout the neighborhood. Color-blocked siding and dark fixtures gave them a modern look, but something about the columns and porches whispered hauntingly of plantation homes.

A loud knock on the driver’s side window snatched me from my reverie.

“Oh my God, Sasha!” I paused the podcast and lowered the window, frowning at my sister as the still-soupy September air punctured my bubble of artificial cool. “You scared me half to death.”

Sasha rested her elbows in the open window, peering at my phone in the cup holder.

“Those podcasts make you so jumpy,” she said. “I thought you got out of journalism so you could get away from that shit.”

It had been nearly ten years since I’d left the crime beat at the

San Francisco Chronicle. With a decade of distance, and no responsibility to investigate the stories myself anymore, I found the podcasts oddly satisfying, scratching a very specific itch by unraveling each mystery in forty-five minutes or less.

Rather than try to explain all of this to Sasha, I asked, “Why are you loitering in the yard?”

“Actually . . .” Sasha twisted one of her long dark braids around a finger, an annoyingly childlike gesture for a thirty-five-year-old. “I was hoping you’d let me borrow the car for a sec.” I rolled my eyes. “Please? I’ve gotta get away from Mom for a minute. You don’t know what it’s like. You get to stay in a hotel; I’ve been with her this whole time.”

“How is that different from living with her in L.A.?”

“Ugh, please?” Sasha whined. “I’ll bring coffee when I come back.”

“Fine,” I said, getting out of the car and dropping the keys into her waiting hand. “But make mine an iced vanilla latte.”

“Thanks, Sis!” Sasha cried, wrapping her arms around me. She pulled back, biting her lip. “Think I could borrow a few dollars for the coffee?”

“Oh my God, girl,” I grumbled.

It was dark and cool inside Grammy’s house, thanks to the shade of the oak trees surrounding the property. A bouquet of cooking oil, jasmine perfume, and Luster’s Pink hair lotion lingered in the air. I felt a twinge of regret that I didn’t remember if that was what Grammy had smelled like; it had been at least ten years since my last visit.

“Syd? That you?” My mother’s voice rang out from the dining room. Large cardboard boxes stood in front of the long polished wooden table, their mouths hanging open. Mom looked chic in a crisp striped shirt tucked into black jeans, belted at the waist. Her sleek Angela Bassett–inspired pixie cut gleamed in the light of the chandelier.

“You look way too nice to be packing up this house,” I said.

She shrugged. “Wanted to look presentable in case any more of Grammy’s church friends stop by.” Her eyes slid down my designer workout gear. “Are you going for a run or something?”

“No,” I replied indignantly. I wanted to tell her I was so bloated from all the drugs pushing my ovaries into overdrive that athleisure was all I could stand to wear. “I could be going to brunch in L.A. in these clothes, Mom,” I said instead.

“Yeah, well, this isn’t L.A.” It was true that I only saw my mother in workout clothes when she was on her way to or from a run, despite her having lived in activewear-loving L.A. for more than forty years. Maybe this was a holdover from her own proper Southern upbringing. Mom grew up in suburban Atlanta, the only child of a Morehouse-educated Baptist pastor and a Spelman-educated bookkeeper. They’d long given up on their dreams of having children before learning of my mother’s pending arrival. I had vague memories of visiting them in the home my mother grew up in when I was small; they were stiffly loving and frail, and their house had the formal, frozen quality of a fancy dollhouse. They both died before I reached middle school.

My mother pushed a roll of garbage bags into my hands. “Can you take care of the guest room in the back? We’ve got three piles going here: trash, Goodwill, and keepsake. Don’t be too precious about keepsakes, though. We don’t want to ship too many things back home.”