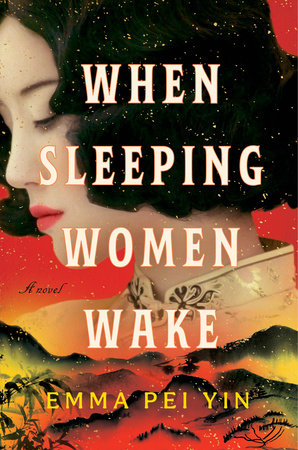

Excerpt

When Sleeping Women Wake

Chapter 1In the heart of the family library, Mingzhu turned the page of her copy of Dream of the Red Chamber. As the characters moved, she imagined their silk robes flowing, their whispering touch caressing her skin. A ceiling fan, crafted from polished wood, rotated above her, emitting a soft hum, providing relief from the torrid discomfort of July.

When the words began to blur, Mingzhu shifted her focus toward the windows. The afternoon light filtered through the glass, cascading over neatly arranged book-shelves that reached the ceiling. Having fled Shanghai and settled in Hong Kong three years earlier, Mingzhu found solace within the walls of the library. Few ventured into its depths, leaving it mainly for Mingzhu and her daughter, Qiang, as a sanctuary from the ceaseless noise of the outside world and the overwhelming presence of her husband’s concubine, Cai. When guests did visit, the men retreated to the downstairs drawing room, accompanied by her husband, Wei, and the women gathered on the terrace, their conversations punctuated by glimpses of the sparkling blue expanse of the South China Sea beyond the mountains. Despite rumors of Japanese forces looming over Hong Kong, the library remained a haven where the echoes of war, which often haunted Mingzhu, felt somewhat distant.

A knock struck the door, and Dream of the Red Chamber slipped from her grasp. She retrieved it quickly and tucked it between plush velvet cushions on the couch. Ignoring her qípáo’s creased and disheveled state, she hastened to a bench near the window and reached for a threaded needle and silk handkerchief.

“Come in.” Mingzhu shifted on the seat, beginning to sew.

A woman tiptoed into the room, and at the sight of her maid, Biyu, Mingzhu relaxed.

Biyu bowed and her long braid, tied neatly with a blue ribbon, slipped over her shoulder. Her tunic and matching trousers were a spotless white. “Good evening, First Madame.” She stepped further into the library, her eyes skimming the room before settling on the couch. “You might want to find a better hiding place.”

Mingzhu wrinkled her nose. “Too obvious, isn’t it?” she conceded, rising from her seat and tossing the needle and handkerchief back onto the bench. She recovered the book between the cushions and returned it to its rightful place on the shelf. From the window, a spotted dove alighted on a branch of a willow tree several feet away.

Biyu began clearing a porcelain teacup and saucer from the low table. “Master Tang allows you to read. Why do you hide it?”

“Allows . . .” Mingzhu fixed her eyes on the dove. For a fleeting moment, she was transported back to her childhood, seated by a window, breathing in fresh ink and watching spotted doves land on towering camphor trees. “I wasn’t hiding the book from my husband.”

“Then, you must be hiding it from the second madame.”

“You know how she can be.” Mingzhu brushed her hands over her qípáo. “She doesn’t think it’s proper for women to read about anything but the latest fashion trends from Europe.”

“But you’re the primary wife. A concubine cannot dictate what you can or cannot read. It’s already a compromise that you allowed her the title of second madame. Frankly—”

Her maid pressed her lips together, refraining from the tangent she had been about to start. Mingzhu gave a small laugh, noting Biyu’s flushed cheeks and protective stance. At forty-one, Biyu had charcoal-black hair, tidy brows, and a gentle countenance, bearing a striking resemblance to Mingzhu. Some days, strangers even mistook them for sisters.

“You know her incessant carping does my head no good.” Mingzhu sighed.

“It is nice when she speaks less,” Biyu agreed thoughtfully.

Mingzhu laughed, then asked, “I assume you have come to tell me my husband is home?”

“Master Tang returned not long ago. He has requested the presence of both wives to join him in the dining hall.”

“Can he not make do with Cai? What difference does one less wife make at the dining table?”

“You’re the main wife. It would be—”

“Yes, I know, I know. Come on, then.”

Mingzhu looked back at her bookshelves, knowing her peaceful evening had been interrupted. Why couldn’t her husband have stayed in his office in the city for one more night? Perhaps two? She left the library with Biyu close behind.

A long rosewood table occupied the center of the grand dining hall. The flicker of glass sconces intensified the already hot room, painting shadows on all assembled. A knot of annoyance and concern coiled within Mingzhu’s stomach as she noticed Cai comfortably seated in her own customary spot. Had Cai forgotten the tenets of family decorum, or did she believe birthing a son allowed her to flout such traditions?

Mingzhu raised a brow, and Cai let out an indignant scoff before pushing her chair back and walking off to her assigned seat at the far end of the table. “How considerate of you to finally join us,” Cai said through clenched teeth.

Her words stung, yet Mingzhu remained poised. It was as if Cai had already forgotten the times Mingzhu had sat tirelessly by her side when they first arrived in Hong Kong, how Mingzhu had held her hand and provided solace during those darkest moments. She chose to ignore the provocation, redirecting her attention to Wei. “Good evening, husband,” she said.

Wei merely nodded in acknowledgment, focusing on his plate of roast beef, potatoes, and sauteed vegetables. Since leaving Shanghai, he had insisted on adopting British dining customs, and the days of savoring mouthwatering braised meat and bowls of pillowy rice with chopsticks had become distant memories. Although the flavors were less thrilling, Mingzhu knew they fared better than those stranded back on the mainland, even if the sustenance lacked the familiar tastes of home. Though Mingzhu didn’t love her husband, she knew that without his swift actions, transferring their finances from Shanghai to Hong Kong before the Japanese invasion, they would not be living in such comfort.

With the Peak District Reservation Ordinance of 1904 still firmly in place, many had raised their brows, pondering how a Chinese family could acquire such a grand estate on the hill. But, as Wei always said, money and connections can buy anything. It was a cruel irony that Mingzhu herself had no wealth to claim. When her parents had passed years earlier, the siheyuan she was born and raised in was handed over to a distant male cousin—a person whom Mingzhu had never known existed, let alone met.

Over time, Mingzhu grew accustomed to the snobbish expressions of her neighbors—elegantly dressed European women who regarded her with contempt every time she ventured outside. The British had always justified the zoning law by citing the third bubonic plague pandemic. But you’d have to be a fool not to recognize it for what it truly was.

“Did you spend the morning in the ancestral hall, Wife?” Wei asked.

Mingzhu nodded at the nonsensical question. Since she had married into the Tang family, there had only ever been one day she missed performing ancestral rites, and that was the day Qiang was born.

“You lit joss sticks, too?”

Another redundant question. Mingzhu almost mirrored Biyu’s eye roll, but she refrained. She replied, “I did. I lit more than usual to pay respect to those who died in the typhoon a few days ago, too.”

“Good,” Wei said, chewing loudly. “These are benevolent traits to have as a wife.”

Cai stabbed her fork into a piece of carrot and shoved it into her mouth.

“You will follow First Madame’s example, Second Wife,” Wei said, taking Cai by surprise. “Even though you’re a concubine, there is no harm in burning extra spirit money for my ancestors in the underworld.”

Cai almost choked. “Surely your ancestors have reincarnated by now! Besides, the British don’t partake in such rituals. I thought we were trying to be more like them?”

There was a hint of audacity in Cai’s voice that Mingzhu found enviable. Cai wasn’t entirely wrong. If Wei wanted to embrace a British lifestyle, performing ancestral rites seemed contradictory. But speaking as freely as Cai did was not a privilege Mingzhu possessed. This concubine had produced a son for the Tang family, while Mingzhu had but a daughter.

With a sturdy jawline and well-defined cheekbones, Cai projected an aura of majestic command. At least five rounds of pearls decorated her neck, and her nails were brushed with the darkest shade of red, adding a striking contrast to her powdered-white skin. She pressed her lips together, forming a subtle expression of disapproval, her authoritative presence causing unease. If Cai’s circumstances had taken a different turn and she had become the primary wife in the family, she could have wielded substantial influence. To Mingzhu, the fact that Cai found herself as a concubine in this lifetime seemed a bitter jest.

Mingzhu noted the subtle flare of Wei’s nostrils, a telltale sign of simmering anger. Maintaining eye contact with Cai, she subtly tilted her head, silently conveying the message of their husband’s rising temper.