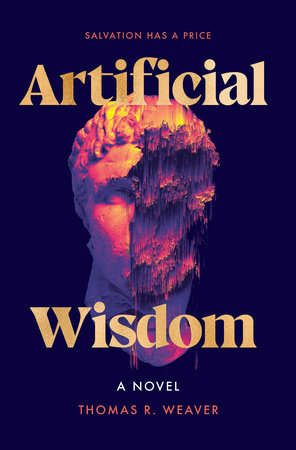

Excerpt

Artificial Wisdom

1London, July 1, 2050Marcus Tully pitched the tumbler as hard as he could at the screen. It slipped through the floating image and shattered against his study wall in a burst of golden rum. He glowered at the undamaged display, still hovering in his vision six feet away. Afternoon sun from the dusty floor-to-ceiling windows glinted off the crystal shards now scattered across the carpet tiles.

“Well,” a pundit sneered at the newscast host, “I just don’t accept the premise of your question. Ten years since this so-called tabkhir hit the Persian Gulf, and I see no credible evidence the heat wave really killed anyone. It was a coup, nothing more.”

Damn all tabkhir-deniers to a humid hell. Ten years since Zainab, his wife, had died. Ten years of holding tight to every memory in case they slipped away when his back was turned.

Shit, he was drunk.

The faint whirr of cleaning bots sounded across the room. He staggered over to the window, placing his palms against the cool glass, then his forehead. Far below, the poor and desperate of London scurried around in the baking summer heat.

Ten years. Ten years today, but it still felt so fresh. Move on, they said. Get over her. But what if he didn’t want to? What if the day he forgot her voice was when she was truly gone?

Play call recording, he told his neuro-assistant. Marcus Tully and Zainab Tully, July first, 2040.

There was a beep—the sound of the old phone systems.

“My love?” Zainab said.

He squeezed his eyes shut at the sound of her voice, so alive, so real, as if he could reach out and touch her.

“Hey, I’m here, Zee,” he said—a man with no idea his world was about to change. “You okay?”

“I’ve been better. Didn’t sleep well. None of us did. It’s too hot, and we’re having brownouts.”

“Pretty warm here too today, though it’s early. Must be eight a.m. in Kuwait?”

There was a pause. “Marcus, it’s really, really humid here this morning, and the heat . . . I can barely move.” Another pause. “It can’t be good for the baby.”

He could still remember the feeling of that first flickering moment of worry, that sudden sharpening of his attention. He opened his eyes again and stared at the skyline.

“But your father has good A/C, right?” Tully said.

“The brownouts, Marcus.” There was a crackle and she cut out for a moment. “—A/C isn’t working. Nothing’s working apart from the phones.”

“Maybe you should come home early? I know your mother wanted to spend time with you before the birth, but—”

“I’ll come,” she said, too fast. “Let me know when you’ve booked the ticket, I can’t do it from here. The connection is as bad as the air—”

There was another crackle, then nothing more.

“Zee?” he said. “Zainab? Can you hear me?”

But she was gone. It burned him up, not to know what really happened to her in the hours after that call, like a fathomless acid in his belly.

He lurched over to the desk and grabbed the rum bottle. Where the hell was the glass?

He felt a pang—the physical sensation of an incoming notification, like an artificial tingle deep within his forehead. A second later he could see the message teasing at the upper right periphery of his vision. Red-edged, for an unknown contact. He ignored it and pulled the cork stopper, then took a gulp of the rum.

There was another pang, its message also red. He shook his head now and took another sip. A third pang made him groan, but he looked up.

Tully, read the first message. Got a story you need to hear. Can we meet? Has to be right now.

He glanced at the second message. It read, Government secrets, okay? Not safe.

The third followed. You got two mins, big shot, or I’m going to your competitors. Bradlee maybe. Oh, this also concerns your wife.

The bottle slipped from his hands and smashed on the edge of the desk, releasing a sickly stench. The cleaning bots bleeped disapprovingly. Tully blinked at the last message, reread the first two, then stared again at the third.

She’d been dead for ten years. What the hell would a whistleblower know about it?