Excerpt

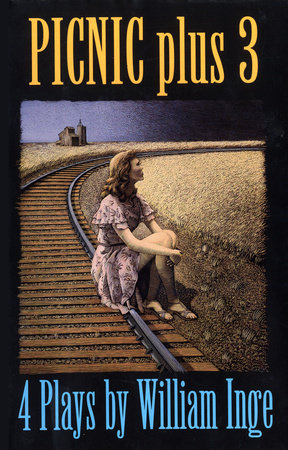

Picnic Plus 3: 4 Plays

FOREWORD

The experience of my first production on Broadway was frantic and bewildering. The play was Come Back, Little Sheba, and it was a modest success. I had always hoped for an overwhelming success, but I felt myself very satisfied at the time that Sheba had come off as well as it did. Anticipating success (of any degree), I had always expected to feel hilarious, but I didn’t. Other people kept coming to me saying, “Aren’t you thrilled?” Even my oldest friends, who had known me during the years when I gave myself no peace for lack of success, were baffled by me. There was absolutely no one to understand how I felt, for I didn’t feel anything at all. I was in a funk. Where was the joy I had always imagined? Where were the gloating satisfactions I had always anticipated? I looked everywhere to find them. None were there.

A few weeks after Sheba opened, a newspaper woman from the Midwest came dancing into my apartment to interview me, bringing with her a party spirit that could not counter with my persisting solemnity. “Where’s the celebration?” she wanted to know, looking about the room as though for confetti. “Where’s the champagne?” I knew I was not meeting success in the expected way but I was too tired to fake it. I endured her disappointment in me. I could tell by her twitching features that she was wondering what in the world she would tell her readers. Obviously, she couldn’t tell them the truth, that the man who had written a (modestly) successful play was one of the saddest-looking creatures she had ever seen. But she didn’t let the facts bother her. She returned home and wrote of the play’s success and my reaction to it in a fitting way that wouldn’t let her readers down. At the time I was too depressed to care.

Other people, friends and aquaintances, couldn’t imagine why I had started being psychoanalyzed at this time. “But you’re a success now,” they would assure me. “What do you want to get analyzed for?” As though successful people automatically became happy, and psychoanalysis were only a remedy for professional failure. But if the personal rewards of my success were a disillusionment to others, they also were to me. My plays since Sheba have been more successful, but none of them has brought me the kind of joy, the hilarity, I had craved as a boy, as a young man, living in Kansas and Missouri back in the thirties and forties. Strange and ironic. Once we find the fruits of success, the taste is nothing like what we had anticipated.

Maybe the sleight of hand is performed during the brief interval of rehearsals, out-of-town tryouts, and opening night. A period of six or more weeks that pack a lifetime of growing up. During that period, the playwright comes to realize, maybe with considerable shock, that the play contains something very vital to him, something of the very essence of his own life. If it is rejected, he can only feel that he is rejected, too. Some part of him has been turned down, cast aside, even laughed at or scorned. If it is accepted, all that becomes him to feel is a deep gratefulness, like a man barely escaping a fatal accident, that he has survived.

All my plays have survived on Broadway. All have met with success in varying degrees. And I feel a fitting gratefulness, because they all represent something of me, some view of life that is peculiarly mine that no one else could offer in quite the same style and form. Success, it seems to me, would be somewhat meaningless if the play were not a personal contribution. The author who creates only for audience consumption is only engaged in a financial enterprise. There must always be room for both kinds of theatre, but it is regrettable that they must always compete together in our commercial theatre. For commercial theatre only builds on what has already been created, contributing only theatre back into the theatre. Creative theatre brings something of life itself, which gives the theatre something new to grow on. But when new life comes to us, we don’t always recognize it. New life doesn’t always survive on Broadway. It’s considered risky.

People still come to me sometimes to tell me how much they admired Come Back, Little Sheba, referring to the play as though it had been “a smash hit” (a term which we are too eager to apply to shows). Actually, Sheba made out well with about half of the reviewers, its total run being something less than six months. Some of the reviews showed an almost violent repugnance to the play. We did good business for only a few weeks and then houses began to dwindle to the size of tea parties. At one time, the actors all took salary cuts, and I took a cut in my royalties. The show was cheap to run, and so, with a struggle, we survived. We always held a small audience of people who were most devoted to the play and came to see it many times. It is remembered now as “a smash hit” or “a hit,” probably because the far greater success of the movie shed more glorious reflections on the play.

Now, I don’t see how it could have been otherwise with Sheba. It is probably a bad omen if any author’s first play is “a smash hit.” It takes the slow-moving theatre audience one or two plays by a new author, who brings them something new from life outside the theatre, before they can feel sufficiently comfortable with him to consider fairly what he has to say. A good author insists on being accepted on his own terms, and audiences must bicker awhile before they’re willing to give in. One learns not to be resentful about this condition but to credit it to human nature.

I have a tendency, after a play of mine is produced, to look back on it disparagingly, seeing only its faults (before production, I see only its virtues). But after the hiatus of opening night, after enough time passes for me to regard each play seriously, as something finally distinct from myself, I have felt that each one gave me some feeling of personal success, that each one contributed something to the theatre out of my life’s experience.

I have never sought to write plays that primarily tell a story; nor have I sought deliberately to create new forms. I have been most concerned with dramatizing something of the dynamism I myself find in human motivations and behavior. I regard a play as a composition rather than a story, as a distillation of life rather than a narration of it. It is only in this way that I feel myself a real contemporary. Sheba is the closest thing to a story play that I have written, and it is the only play of mine that could be said to have two central characters. But even this play was a fabric of life, in which the two characters (Doc and Lola) were species of the environment. After Sheba, I sought deliberately to fill a larger canvas, to write plays of an over-all texture that made fuller use of the stage as a medium. I strive to keep the stage bubbling with a restless kind of action that seeks first one outlet and then another before finally resolving itself. I like to keep several stories going at once, and to keep as much of the playing area on stage as alive as possible. I use one piece of action to comment on another, not to distract from it. I don’t suppose that in any of my later plays I found the single dramatic intensity of action that I found in the drunk scene in Sheba, in which Doc threatens Lola’s life. I have deliberately sought breadth instead of depth in my plays since Sheba, and have sought a more forthright humor than Sheba could afford.

In an article I once wrote on Picnic, I compared a play to a journey, in which every moment should be as interesting as the destination. I despair of a play that requires its audience to sit through two hours of plot construction, having no reference outside the immediate setting, just to be rewarded by a big emotional pay-off in the last act. This, I regard as a kind of false stimulation. I think every line and every situation in a play should “pay off,” too, and have its extensions of meaning beyond the immediate setting, into life. I strive to bring meaning to every moment, every action.

I doubt if my plays “pay off” for an audience unless they are watched rather closely. Writing for a big audience, I deal with surfaces in my plays, and let whatever depths there are in my material emerge unexpectedly so that they bring something of the suddenness and shock which accompany the discovery of truths in actuality. I suppose none of my plays means anything much unless seen as a composite, for I seek dramatic values in a relative way. That is, one character in a play of mine might seem quite pointless unless seen in comparison with another character. For instance, in Bus Stop, the cowboy’s eagerness, awkwardness, and naïveté in seeking love were interesting only when seen by comparison, in the same setting, with the amorality of Cherie, the depravity of the professor, the casual earthiness of Grace and Carl, the innocence of the schoolgirl Elma, and the defeat of his buddy Virgil. In themselves, the characters may have been entertaining, but not very meaningful.