Excerpt

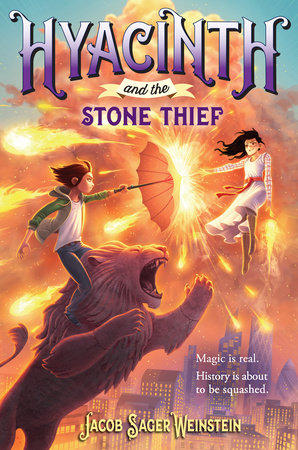

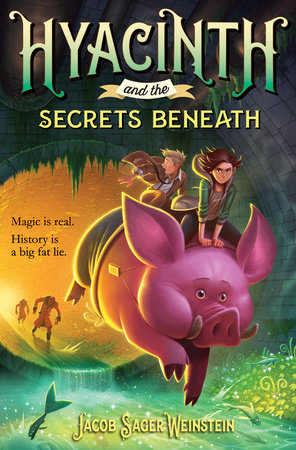

Hyacinth and the Stone Thief

I had saved London, and my mother, and possibly the entire world. I had uncovered a vast magical conspiracy stretching back centuries.

Not bad for one week of summer vacation.

Still, it wasn’t enough. I wanted to know

why. I wanted to know why a group of sewer-dwellers thought I was a valuable magical treasure. I wanted to know why my mother’s blood was so powerful that a mysteriously strong elderly lady had tried to drain it. I wanted to know why Mom’s memory was supernaturally bad.

Most of all, I wanted to know why my family was linked to the secret magical rivers that ran under the streets of London. I was pretty sure

that why would answer all my other questions. And if I didn’t get them answered—well, I had a feeling that Lady Roslyn wouldn’t be the last person who wanted to get her hands on Mom’s blood.

When most kids have a question about their family history, they just ask their parents. Believe me, I tried.

I asked Mom, but she had a hard enough time remembering the details of yesterday’s breakfast, let alone decades past.

I called my grandma and every one of Mom’s eight sisters, and none of them answered the phone. None of them answered my emails. In desperation, I even sent them actual postal letters, which I hadn’t done since I was little. I doubted any of them would write back, but Grandma had raised all nine of her daughters to be big on putting things on paper, so there was at least a chance that a handwritten note would prompt some sort of reaction.

I even called Dad in America. It wasn’t his side of the family—but at least he was taking my calls. “What do you know about Mom’s family?” I asked him.

“Well, Hyacinth, Mom and her sisters grew up in London and then moved to America. And Grandma’s parents were from Greece.”

“I know that,” I said. “But don’t you think it’s weird that that’s all we know?”

“I never met Grandpa Herkanopoulos, but I gather he had some huge fight with his father and cut off all contact. And your grandparents were cousins—which wasn’t considered that weird in the old country—so cutting off Grandpa’s family meant cutting off Grandma’s, too. It all sounded very painful, which is why I always figured Grandma didn’t want to talk about it.”

And that was it. That was the best answer I could get.

If nobody in my family could explain our mysterious connection to London, maybe

London could. Maybe if I retraced my steps, I’d be able to spot new clues, now that I didn’t have the whole trying-to-save-my-mother-from-doom thing to worry about.

Lady Roslyn and I had entered the sewers through a manhole outside a dusty and faded shopping arcade near Baker Street station, so that’s where I started. The manhole cover was still there, as was the battered marble fountain next to it—but the entire arcade had vanished. Where once there had been a large arch, there was now a solid wall.

After splitting off from Lady Roslyn, I had gone to the top of the Monument to the Great Fire of London with my friend Little Ben and a giant pig named Oaroboarus, and it had fallen completely on its side, exposing the hole beneath it where a magical fire hook was kept. The Monument was standing upright back in its usual place, of course, but in the plaza next to it, at the exact spot where the Monument had landed, there was a small one-story building, built out of stone blocks covered with reflective glass. The sign on the door said it was a restroom—but if you were going to build something to stop a giant, heavy monument from lying flat, and to bounce off any magic that hit it, that’s what you’d end up with.

Everywhere I looked, damage had been repaired.

Entrances had been sealed. The only evidence of my adven- ture was the care that somebody had taken to cover it up. And an antique stamp that had still been in the pocket of my sewage-soaked jeans when I finally changed out of them. After it dried, I had tucked it into my cell phone case so that I could look at it whenever I started to think I had imagined everything. During my long day of fruitless investigating, I had looked at it a lot.

So when I trudged up the three flights of steps to Aunt Polly’s flat, I was tired and frustrated.

Then I noticed that the door to the flat was open.

I ran inside. “Mom?” I called. There was no answer.