Excerpt

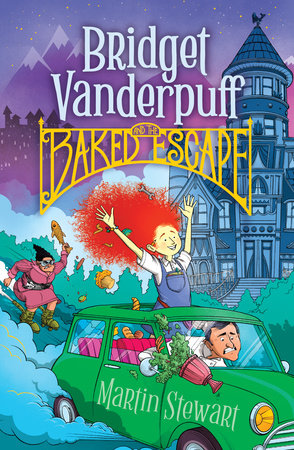

Bridget Vanderpuff and the Baked Escape #1

1 A Daring Rescue bear traps * lockpicks * stuffed dodos

The world outside was swollen with new snow, and its light cut the room like a torch beam.

Bridget Baxter slid a lockpick from her teeth.

“How much longer?” whispered Tom.

“Just a couple of minutes.”

“You said that a couple of minutes ago.”

Bridget raised an eyebrow. Tom clamped his hands over his mouth.

“I’m going as fast as I can, and besides,” Bridget checked the Listening Glass she’d slipped under the door, “she’s not even in the corridor yet. Calm down.”

“

Calm down?” hissed Tom. “You’re not the one with your leg in a bear trap! And for

what? Talking with my mouth full of breakfast?”

“

Singing with your mouth full,” corrected Bridget. She reached into her thicket of orange hair, found a tweezle-tip lockpick, and eased it into the enormous padlock. “And you

were standing on the table.”

Tom shrugged.

“I had to make sure everyone could hear me.”

They giggled silently. Dust sank through the snow-light and settled on Miss Acrid’s many hideous things.

On the badly stuffed birds and unread books.

On the stern marble busts and murky paintings.

On the jars of eyeballs and cat-skull cups.

And on Miss Acrid’s gigantic, soggy sandwich. Bridget looked at the sandwich, which sat in the center of Miss Acrid’s enormous desk.

Shuddering, she closed her eyes and let her mind drift into her lockpicking hand, shutting down her senses until all that remained was the skin of her fingertips—five little antennas, listening to the lock’s secret whispers.

“What are you

doing?” whispered Tom urgently.

“You don’t use your eyes to see inside a lock,” said Bridget softly. “You see through your fingers.”

“You read that somewhere, didn’t you?”

“Of course.”

“In a big, long book?”

“Yes,” said Bridget. “A wonderful book, full of bravery and love and fun.”

“And padlocks?”

“Yes. Now shush—I’m trying to listen.”

“Through your fingers?”

“Yes!” hissed Bridget. “Are you

incapable of silence?”

Tom picked the feathers from a stuffed dodo.

“The Families are coming today,” he said. “Last time, Poppy Parker went to live on Easy Street.”

“That’s not a real street, you know,” said Bridget. “It just means her new parents are rich.”

Bridget remembered it well: Poppy had been whisked away in a handsome, electric airship. Bridget had watched from her hiding spot among the library’s chimneys and gargoyles, following the airship’s gleaming copper past the village of Belle-on-Sea, toward the great towns and cities beyond the hills.

She thought about the people who came to the Orphanage only once a year, looking for children to love. She imagined their caramel coats and comfortable houses; their glossy hair and wide smiles; how she wished a sweet-smelling family would spread their arms, wrap her in the tightest most wonderful hug—and take her far, far away from the Orphanage for Errant Childs.

But she shook her head, scattering the vision. A shower of sparks burped from the fire.

“What are you thinking about?” said Tom.

Bridget paused for a moment. Tom squeezed her shoulder.

“Maybe this time—”

“This time will be the same as all the others,” said Bridget, turning her attention back to the lock. “Whenever the Families come, Miss Acrid makes sure I’m shut away, or helping the janitor, or . . . climbing the chimney stacks! It’s never my turn. I’ll never find a real

home. I’ve already been here

nine years.”

“But that isn’t so long, really, I mean, some people live to a hundred. Some tortoises live to two hundred! And some rocks have been around since—”

“I’m not a tortoise, though,” said Bridget, twisting the lockpick with a

sproink, “or a pebble. When you’re nine years old, nine years is forever—I’ve been here

forever. And forever is for ever and that’s that. I’ve seen

countless Childs find new families, and I—What are

you

doing to that dodo?”

“I’m trying to make him look like Miss Acrid,” said Tom, wrinkling his nose and leaning away from the stuffed bird. Its eyes had narrowed, and the eyebrows were closer together.

“That’s pretty good,” said Bridget. “It’s just right. Sort of . . . surprised about being constipated.”

Tom pushed the dodo’s eyebrows even closer and puffed out its cheeks.

“You always get the better of Miss Acrid. How many times have you been thrown into the dungeon?”

Bridget shrugged.

“I stopped counting after the first hundred.”

“Remember when she dropped you in the Bottomless Pit? You were back in her office before she was!”

“Well,” said Bridget modestly, “she shouldn’t call it

bottomless if—”

“I can’t

believe you hid her Mistress medallion!”

“You’d think,” said Bridget, “she would

check her sandwiches—”

“And what did she say when you filled all her teabags with glitter?”

Bridget hopped to her feet, pulling her unruly hair over her ears.

“Baxter!” she cried, in perfect imitation of Miss Acrid’s shrill and shrieky voice. “

Whaaaaii is my break-fast-brew so spark-elly and shyyy-naaaaaay?”

They giggled again.

“You will find a real home, Bridget,” said Tom. “I know you will.”

Bridget’s tummy knotted up tight, and she blinked very quickly.

“We both will,” she managed. “We’ll—”

She turned her head.

“What?” said Tom. “What is it?”

Bridget grabbed the Listening Glass: footsteps—unmistakably Miss Acrid’s—thundered in her ears.

“She’s coming!”

“Oh,

no!” whispered Tom. “Run, Bridget—go! There’s no sense in you getting caught when it was me who—”

But Bridget was already kneeling beside the bear trap, eyes tightly shut.

“Bridget—”

“Ssh!”

The Listening Glass was hopping on the floor.

“Go! You needn’t—”

“

Sssshh!” hissed Bridget.

Trying to ignore the rumble of approaching boots, she followed the clever little pattern of the padlock’s pins, working the lockpick with twists and tickles and taps until, with a satisfying, solid

thunk, the pins sang their secret song—and the padlock fell apart.

“You did it!” cried Tom, rubbing his leg as Miss Acrid’s footsteps drew nearer. “But

now what do we do? We’re trapped!”

Bridget kicked the window, which swung open with a scrape of powdery snow.

A sharp wind cut the children’s cheeks.

“Out of the

window?” said Tom. “But—”

“I made this from a thousand elastic bands,” said Bridget, unwinding a long rope from around her waist, “for exactly this situation.”

“You made this so we could jump out of Miss Acrid’s window after you’d freed me from a bear trap I got put in for singing ‘Look Out, Mr. Chipmunk!’ while standing on a three-legged table with one foot in a bowl of cold porridge and the other on a piece of burnt toast?”

“Well, maybe not

exactly this situation,” said Bridget, tying one end of the rope to Miss Acrid’s enormous desk, and the other around Tom’s middle.

Tom peered uncertainly into the gardens. The distant trees looked like pieces of frosted broccoli, and the Great Maze—a wintery labyrinth of thickets and leaves—sprawled toward the horizon.

“Will it take my weight?” he said.

“Definitely,” said Bridget. Then, because she never lied, added, “Probably.”

“

Probably?” screamed Tom, vanishing out the window.

The door burst open.

Miss Acrid, her battleship bosom trembling with rage, her battle-ax nose flaring and high, burst into the room.

“

Baxter?” she screamed, flexing her grubby fists. “

This time you’ve gone

too far! I’m—”

Bridget picked up the Mistress’s disgusting breakfast sandwich. It was heavy and wet and smelled like rotting seaweed.

Miss Acrid froze.

“Now, Baxter . . .” she said carefully, “don’t do anything silly.”

“Silly like what?” said Bridget. “Silly like eat your horrible breakfast?”

Miss Acrid took a clomp forward.

“You don’t want to do something you’ll regret,” she said.

She took another clomp, her giant boot throwing up a cloud of dust.

“Is that so?” said Bridget.

Miss Acrid’s eyes widened.

“Be

sensible,” she snarled. “And . . . put . . . down . . . my . . . breakfast.”

Bridget stared into the Mistress’s black eyes.

“You know, Miss Acrid,” she said. “I read somewhere that you only regret the things you

don’t do.”

And she bit so far into the disgusting sandwich the crusts touched her ears.

Miss Acrid went purple, mouth flapping as she filled her lungs with one of her legendary screams.

Bridget hopped onto the enormous desk—and jumped out the window.