Excerpt

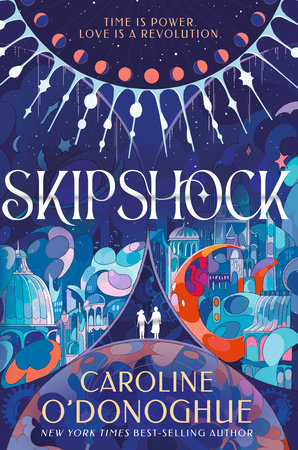

Skipshock

MoonThe most common response I get when I tell people what I do for a living is: I couldn’t do a job like that. What they mean is they

wouldn’t do a job like this. Every so often a new gruesome story circulates about salesmen, and what traveling between time speeds does to one’s physical health.

We are twice as likely to be alcoholics, three times as likely to die by suicide, and infinitely more likely to disappear without anyone caring at all.

But all I ever say is—you’re right. You

couldn’t do a job like this. You couldn’t haggle in a language that you don’t speak. You couldn’t fall asleep anywhere, training your body to relish fifteen-minute-long seated naps in the middle of a busy market square. And you couldn’t wake up the way we do.

Salesmen wake up like dogs. Snoring one second, barking at a stranger the next.

I wake up on the train. Somewhere between Crader and New Davia I feel the train car screech against a tunnel, and have the slightly spectral sensation of knowing—even with my eyes closed—that I am being watched. The tangled gari beads are pressed between the seat and the nape of my neck, leaving light indents in my skin.

“Hello,” I say, eyes fluttering open. Everything about the stranger tells me she’s in the wrong place. First of all, she’s a

she. You rarely get women travelers these days, unless they’ve got a visa to work a special trade, and she looks too young and too out of sorts for that to be the case. Every detail uncovers a new question. Questions like: Why is she wearing summer clothes, on a train heading this far west? Why is she wearing a man’s watch that doesn’t fit her wrist? I squint at the glint of light catching the clock’s face. It’s heavy. Expensive. Silver.

“Hello,” she responds anxiously. The longer I look at her, the more her strangeness unfurls like new petals. Frantic green eyes glancing worriedly down at an orange slip, a paper rectangle no bigger than her palm. “You’re in my seat.”

I gesture around the empty train car, arms wide with emphasis. Evidencing that there are quite a

few

seats free, and it’s rather churlish of her to be protective of this one.

“There is no

my seat,” I reply. “This is the Northwest quad—no assigned seating. Who are you?”

She says nothing. Just shows me her orange rectangle, creased in her nervous hand. I take it from her and read it aloud like I’ve been handed a story written by a small and imaginative child.

“13:05 single,” I read. “Cork Kent to Dublin Heuston.”

She looks at me expectantly. “Am I near?” she asks, the hope draining from her speech. “Am I near Dublin?”

I hand the bright stub back to her. I’ve never heard of where she’s from or where she’s going to. I choose not to share this information. Salesmen are supposed to know about everywhere. The licensing tests are rigorous. They give you a big empty train map to mark with every world station, and it’s 90 percent pass-fail. They want to make sure you know every world so there’s less plausible deniability if they catch you in the wrong one with the wrong visa. Perhaps she’s a plant. A test. A mole. Some new plan of Semper’s, designed to trial our memories, our sympathies, and our resistance to a pretty face.

Pretty face comes to me unbidden, instinctive, the way “sleep tight” might follow a softly uttered “good night.” It presents itself to me in a childish way, because even though she’s about the same age as me, she reminds me of childhood. The wild hair—red, but nowhere near a natural color. The big eyes. The willingness to show fear to a stranger.

Fear. It’s something I’ve tried to grow beyond. I’m not an idiot, and I don’t think of myself as superhuman. I’m victim to the same thoughts and emotions as anyone else. But I do think that in almost all cases you can subdivide large emotions into smaller ones—fear into anxiety, love into affection, empathy into sympathy—therefore protecting yourself from those who will reliably take advantage. In the way insects will cloak themselves to look like their surroundings, I will respond blandly, in the hopes that blandness will cover me and that peace will follow.

It is only very traumatized people, Ves once told me, who confuse stasis for peace.

This person, meanwhile. This person is making no secret of her feelings. She’s completely animated by fear, and for a few seconds, I simply stare at her. Her uneasy eyes flitting all around the train car. Her breath running short. Fingers fidgeting at her hair, then her scalp, then at the cuticles on her other hand.

“Why don’t you sit down?” I suggest.

We sit, uneasily, in a moment of mutual study. Now that she’s across from me, her eyes level with mine, I can feel her digesting my appearance. To be fair to her, it’s a lot to take in. The crescent moon that starts above my left eyebrow and hugs around my cheekbone is far bigger than most salesmen’s tattoos, its largeness in direct proportion to how much they didn’t want to give a license to a Lunati boy. They dug deeply, sharply, and despite their insistence on professionalism and neutrality, with some spite. The scar was violent red in the beginning. Now, six years on, it has smoothed to a papery beige. I watch her watching me. She forgets her panic for a second, because she is wondering how a person could end up with a scar that is so aggressive, yet so precise.

“The answer is yes,” I say. Eager, for some reason, to get these private thoughts of hers into the open. “It did hurt, and yes, I was awake. And yes, I gave my permission.”

She laughs then, embarrassment briefly overriding terror. “Sorry,” she says. “I was staring, wasn’t I?”

“Oh, not so much that anyone would notice.”

There is a brief trading of apologetic smiles, and then a silence.

Before we continue, I want to say something about that trade and that silence, because it happened so quickly, and no one was there to see it. Among salesmen, there is a practice known as scooping. This means that a salesman “scoops” a bunch of his old inventory into a handkerchief for you at a low price, and while most of it will be useless or cheap or out of date, there will always be something strangely valuable in there. A little gem, or a rare coin, or a kind of glass that you didn’t think they made anymore. Maybe the salesman didn’t realize he was giving it to you. Maybe he holds you in higher esteem than you originally thought.

That’s what it was like with her, during that first train journey. A gemstone was briefly uncovered in silence. She scooped me up, is what I’m saying. Or maybe it was the other way around. The face and the eyes and all the silly red hair. Not red like fire. Red like rust. Red like metal. Red like a chemical spill.

The moment passes. She remembers that she has no idea where she is, and her breath starts coming short. She lays the palm of her hand across her chest, as though trying to block her own heart from escaping.

“My name is Moon,” I say at last. “And I think you’re in the wrong place.”